“Returning to Its Nest”: Capturing the Spirit of Isan Music with Classical Guitar

Sirisan Sobhanasiri

PhD Student

University of Otago

sobhanasiri.sirisan@gmail.comChawin Temsittichok

DMA student

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

chawint2@illinois.eduRecorded on 1 July 2025 at Te Korokoro o Te Tūī Studio, University of Otago, using stereo microphones and a single guitar. Post-production editing was used to join organically performed sections, with no synthetic manipulation involved. Recording and editing by Stephen Stedman.

This submission is presented in the form of a music audio file featuring “Returning to Its Nest”, a new piece created by the author’s collaboration with composer Chawin Temsittichok as part of the former’s research project for a PhD in music with creative components at the University of Otago. The article offers a brief insight into the musical concepts developed through the collaboration to emulate Thailand’s Isan musical aesthetic on the classical guitar.

Isan, the northeastern region of Thailand, is predominantly inhabited by people within the Thai-Lao heritage whose culture features a blend of Buddhism, animism, and Hinduism. Isan music, within the Thai-Laos culture, is known for its light-hearted, energetic, and uplifting character, which distinguishes it from the folk music of other regions in Thailand.

“Returning to Its Nest” emphasizes minute dynamic and timbral changes. It is important to note that this English title slightly deviates from Thai, which would be directly translated to ‘Karawek returns to its nest.’ Karawek (การเวก) is a mythological bird that has a significant presence in Isan beliefs, but it can be confused with an actual bird species, also known as the bird of paradise. While the title makes sense in the Thai linguistic context, it does not convey the same meaning in English.

Program note by Chawin Temsittichok (composer/co-author)

Creative Framework

The author’s project focuses on developing a new composer-performer collaborative framework to create new works to express the Isan musical instrumental styles. These pieces aim to reimagine the styles of representative Isan instruments, including phīn (Thai mandolin), khaen (bamboo mouth-organ), wot (circular pan pipes), and ponglang (wooden xylophone), on the classical guitar.

Taking on both roles as a researcher and performer, the author has collaborated with key Isan traditional musicians to gather musical knowledge, performance practices, and feedback on new works. The process has facilitated the author’s active learning of traditional instruments from local expert musicians, demonstrating Rice’s (2008) “field-play” concept. Through this approach, the author gained insight into the musicality, learning, and cognition of Isan music, simultaneously fostering master-student connections. This apprenticeship status led to improved opportunities for observation and participation in rehearsals, practices and performances, allowing the author to acquire tacit knowledge from the masters (Baily 1995; Rice 2008). The concept of “field-play” is reflected in “Returning to Its Nest” through both innovations in new guitar tuning, inspired by a phīn master’s approach, and in the musical techniques, shaped through observation of an expert khaen player.

The author has also worked with four Thai composers, guiding their musical directions with technical inputs and performing the resulting new pieces. While each of these partnerships applied different creative strategies and focused on different aspects of Isan music, the key parameters were that these new works should present new, yet stylistically appropriate, musical ideas that reflect the aesthetic of Isan music, and also consider the possibility of re-transcription back to the original instruments.

Drawing on Barz and Cooley’s (2008) discussion of emic and etic perspectives in Shadows in the Field, this dynamic of collaboration resonates with both concepts: the emic, through learning directly from local masters, and the etic, through transforming that knowledge into composed works for the classical guitar. The author characterizes his mediation as a “double negotiation,” a process that bridges two musical worlds. This framework method also serves as a way to actively engage with the ethical implications of cultural appropriation by requiring the researcher and composers to remain accountable to the source culture while creating new works from its musical elements. This approach encourages awareness of cultural respect and authenticity in musical decision-making.

The new pieces were composed based on an alternative tuning technique that allows the guitar to authentically perform in the Isan style. The idea about modified tunings was inspired by an approach taken by Rattasart Weangsamut (Weangsamut 2016, 59), who adopted the tuning system from the phīn, an Isan mandolin, for the classical guitar to arrange “Phuthai Samphao”. ( 1 - E4, 2 - A3, 3 - E3, 4 - E3, 5 - A2, 6 - E2 ). However, the technique used in this project was derived from a unique method developed by Kammao Perdtanon, a phīn master from Roi Et, Thailand. It combines multiple phīn tunings, allowing the phīn to perform various styles of Isan music without the need to retune. The author’s scordatura adapts Perdtanon’s concept for classical guitar, enabling idiomatic access to the key drone intervals of the 2nd, 4th and 5th, which are characteristic of traditional Isan sonorities. ( 1 - E4, 2 - D4, 3 - G3, 4 - D3, 5 - G2, 6 - D2 ).

The Compositional Concept of “Returning to its Nest”

The key concept in composing this piece is to emulate the expressive abilities of the khaen, the bamboo mouth organ of Northeastern Thailand and Laos. This versatile multi-pipe wind instrument can play both solo melodic lines and accompaniment simultaneously, making it unique in its ability to blend melody and harmony.

Figure 1: Khaen, the bamboo mouth-organ; photo by author

With its diverse expressive range, the khaen has been adapted into various musical styles, even by foreign artists. Hal Walker uses it in various modern popular genres while Christopher Adler (2007) has demonstrated its broader expressive potential by creating new contemporary compositions as well as promoting others to write for the instrument. “Returning to Its Nest” is interpreted in an imaginative way with a slow pace and a sense of rhythmic fluidity and instability. While still respecting the playing possibilities and textures of the khaen, this piece moves beyond a purely Isan style and becomes more exploratory in musical ideas, yet still preserving the essence of Isan music. This is achieved partly through its pitch organization, which is derived from lai yai, one of Isan's pitch-centric systems, and resembles a minor pentatonic scale featuring a tonic–dominant drone based on a perfect fifth interval.

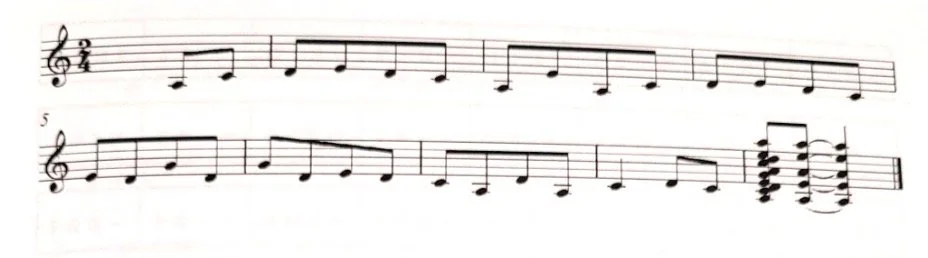

Figure 2 shows an instance of lai yai in a traditional tune. This melody moves within an A minor pentatonic collection, leading to the final chord built primarily from layered perfect fifth intervals. Similarly, Returning to Its Nest, centered around the G minor pentatonic scale, employs the perfect fifth interval as a seed from which its harmony grows.

Figure 2: Excerpt of a khaen Lai Yai tune (เกริ่น) by Klangprasri, The Art of Khaen Playing (2006), 83.

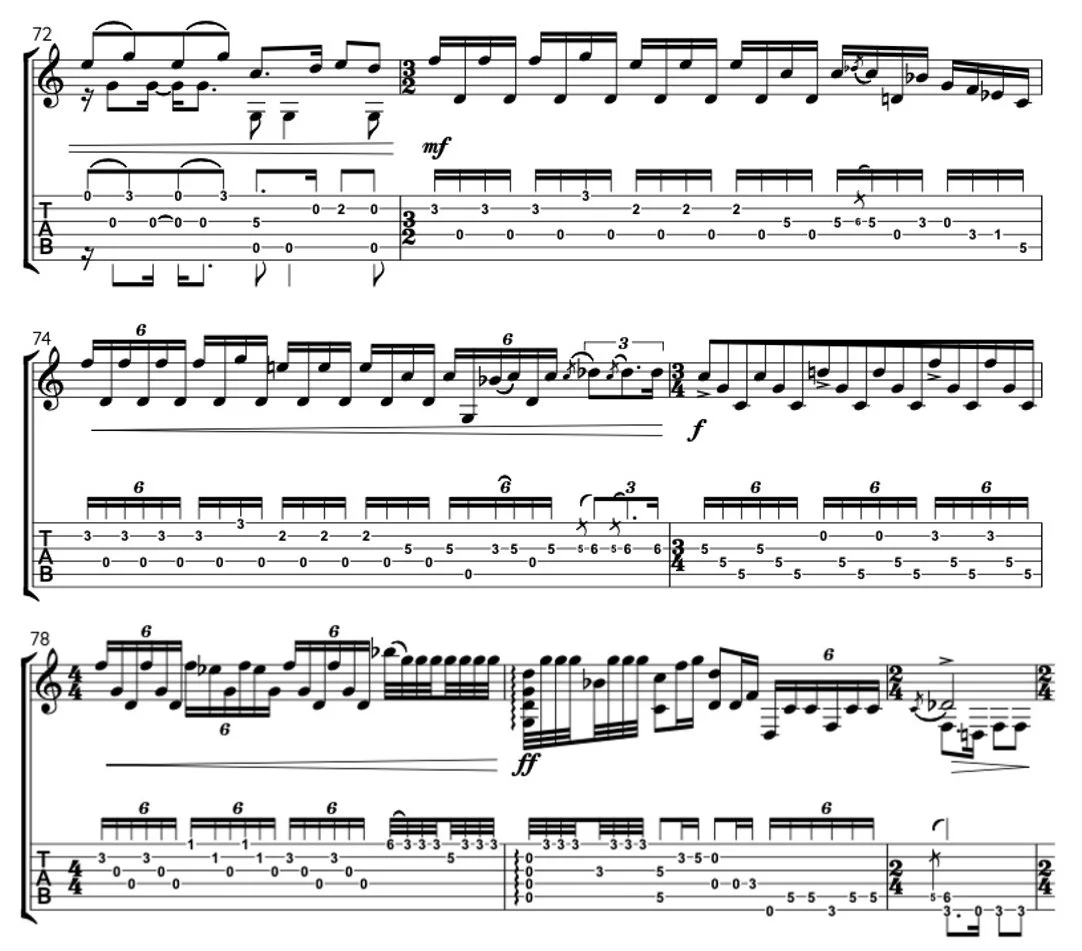

Temsittichok also occasionally uses the raised 6th scale degree, E♮ (See Figure 3, mm. 74) to imitate an intentional off-pitch referred to as siangsom (sour sound) in Isan musical vernacular. Siangsom notes connote a sense of oddness within the sound world and is often used to imply humor in Isan music.

The piece also features notes beyond the scope of the pentatonic collection. In Figure 3, as seen in mm. 73–74 and mm. 78–80, D♭ and E♭ appear in both the melody and the accompaniment function as out-of-key tones within the scale. These two pitches are crucial to how “Returning to Its Nest’ deviates from traditional Isan sonorities.”

Figure 3: Excerpts from mm. 72-75 and mm. 78-80. [4:42-5:22]

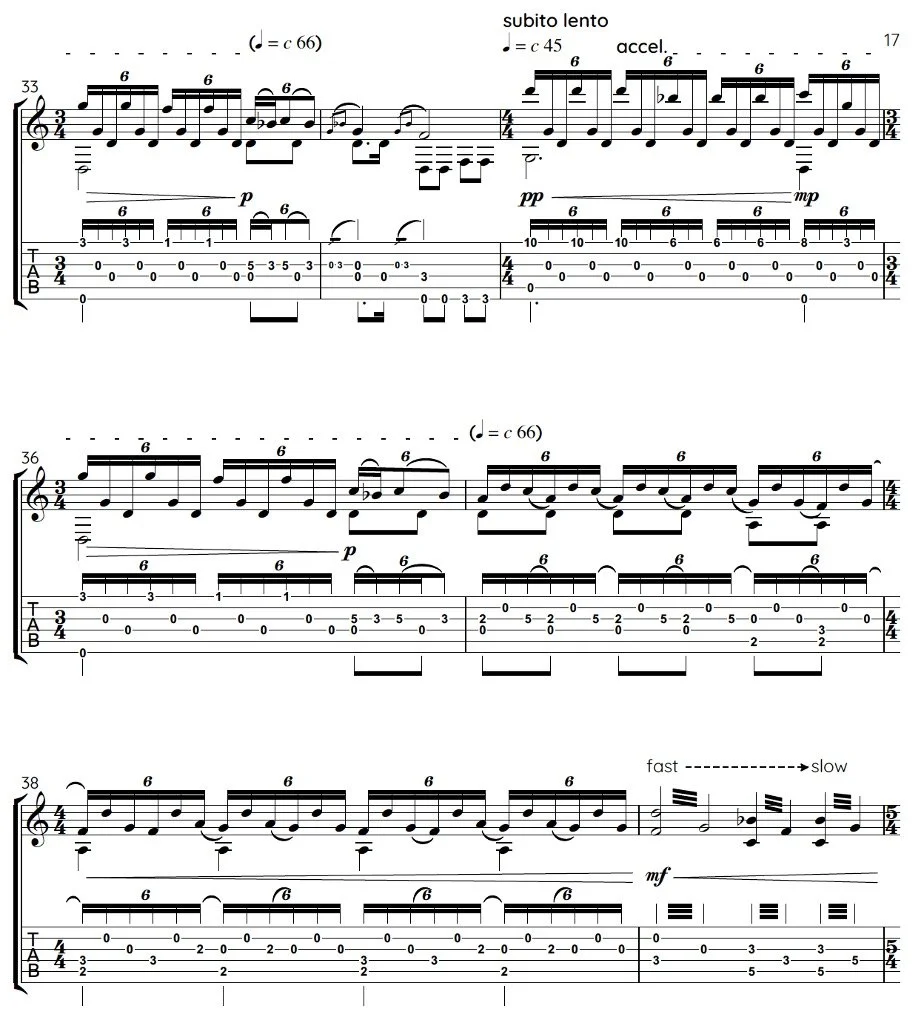

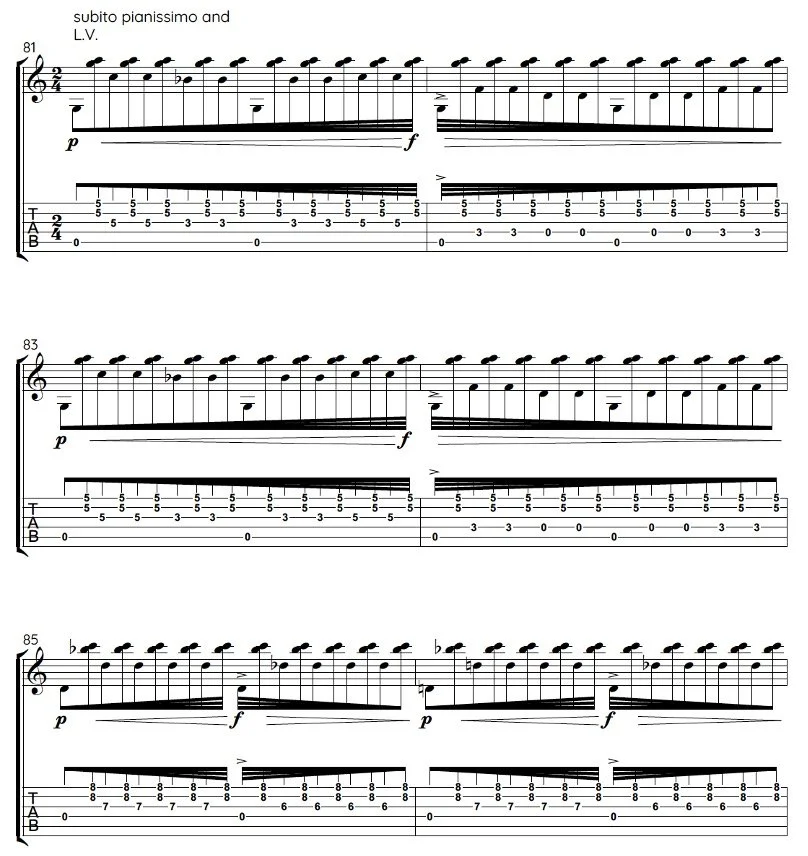

To achieve a sense of fluidity and unpredictability in rhythmic structure, Temsittichok applied three compositional techniques: change of tempo markings, tremolo, and feathered beaming (See Figure 4). These notational strategies aim to make concepts such as dramatic tempo and sudden accelerando or diminuendo shifts more intuitive and flexible for the performer.

Figure 4: Change of tempo markings and tremolo [2:14-2:40]

At measure 35 (Figure 4), a marked tempo change signals the dramatic shift in tempo, followed by an accelerando leading to a new tempo marking. It is more practical to notate an acceleration of a longer gesture, which is two measures in this instance.

At measure 39 (Figure 4), the accelerando is marked with text instead of notation to specify that the acceleration only applies to the tremolo rates and not the tempo. Temsittichok’s use of tremolo speed to represent both the increasing and decreasing of sound intensity, combined with dynamic markings, has effectively depicted khaen performance techniques and creatively extends upon its sound.

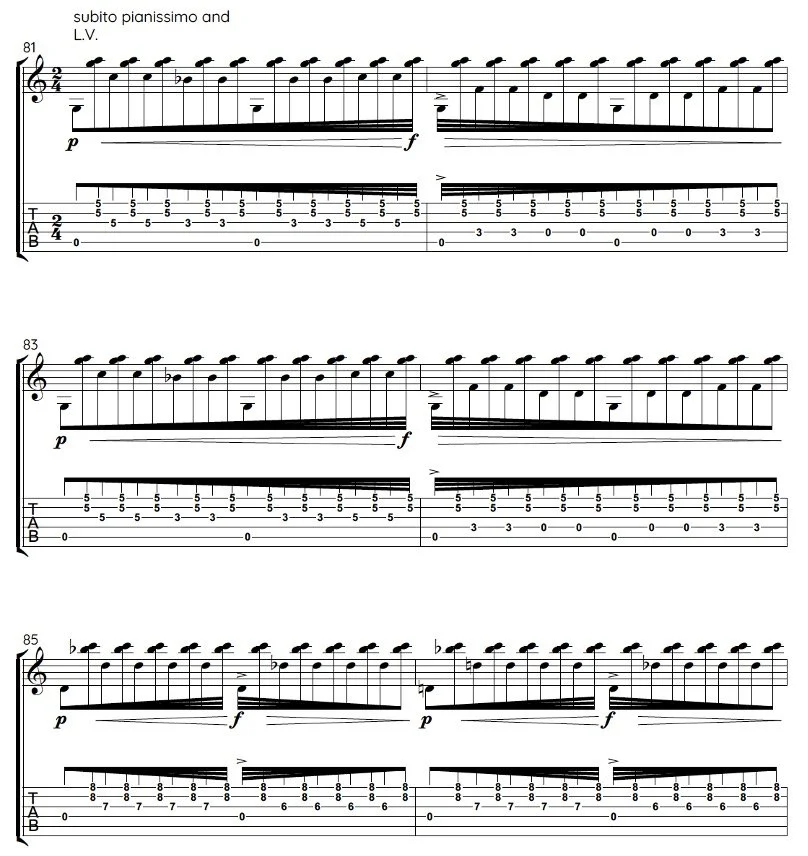

Figure 5: Example of feathered beaming [5:22-5:46]

In Figure 5, rather than explicitly marking accelerando or ritardando for each phrase, the feathered beaming visually suggests the rise and fall in rhythmic energy, giving performers a more intuitive way to interpret the phrasing. The musical idea refers to the gestural imitation of khaen chords, a core expressive element in traditional Isan music. The feathered rhythms mirror the swelling and tapering of airflow through the khaen, emulating its chordal gestures and dynamic breathing-like phrasing. Additionally, at measure 85-86, the D♭ creates a clashing dissonance with D♮. Temsittichok cited blues music as the inspiration for this moment. The harmonic event closely resembles the function of the “blue note” in American jazz and blues, which performers often describe as a note that is “worried” or “bent.” In these traditions, musicians and singers frequently create melodic variation by altering the 3rd, 5th, or 7th scale degrees in relation to the central tonality (Kubik 2013).

Conclusion

“Returning to Its Nest” merges pitch organization and rhythmic fluidity with specific classical guitar techniques to metaphorically evoke the playing style of the khaen. Alternative guitar tuning enables access to Isan musical ideas and techniques challenging or impossible on a standard-tuned instrument. Though not a perfect substitute for the khaen’s timbre and sustain, the new tuning produces a resonance that evokes the characteristic sound of Isan music.

References

Adler, Christopher. 2007. Khaen, the Bamboo Free-Reed Mouth Organ of Laos and Northeast Thailand: Notes for Composers. Updated March 2023. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs License. Accessed August 25, 2025.

Baily, John. “Learning to Perform as a Research Technique in Ethnomusicology.” British Journal of Ethnomusicology 10, no. 2 (2001): 85–98.

Barz, Gregory F., and Timothy J. Cooley, eds. 2008. Shadows in the Field: New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology. Oxford University Press.

Klangprasri, Sanong. 2006. ศิลปะเป่าแคน: มหัศจรรย์แห่งเสียงของบรรพชนไทย [The Art of Khaen Playing: Miracle of Thai Ancient Voices]. Mahidol University.

Kubik, Gerhard. 2013. “Blue note.” Grove Music Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.A2234425

Rice, Timothy. 2008. “Toward a Mediation of Field Methods and Field Experience in Ethnomusicology.” In Shadows in the Field: New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology, 2nd ed., edited by Gregory F. Barz and Timothy J. Cooley. Oxford University Press.

Weangsamut, Rattasart. 2016. “Arranging of Phu Thai Sam Phao Song for Classical Guitar Solo by a Technique of Adjusting Guitar String to Pin.” Journal of Integrative Business and Economics Research 5 (NRRU): 59.