Corridos as Citizen Diplomacy: Cultural Impact of Corridos in The U.S.-Mexico Border Regions

Kevin Perez

M.M. Student, Clarinet PerformanceSchool of Music, The Pennsylvania State UniversityKap6480@psu.eduINTRODUCTION

For over a century, corridos, a style of traditional epic Mexican ballads, have told stories of heroes—both fictional and non-fictional—at odds with villains and oppressive forces. Today, they are often used as a tool for protest and unity, detailing the stories of migrants facing economic hardships, racial violence, discrimination, and oppression. This article focuses on corridos by Los Tigres del Norte, a Mexican musical group based in San Jose, California. I make a case for their performances as a form of citizen diplomacy, creating transnational cross-cultural understanding and knowledge. I also argue that these performers realize themselves as diplomatic cultural intermediaries.

Citizen diplomacy is a term first coined in the l960s by Ambassador Edmund Gullion, Dean of the Fletcher School at Tufts University. Sherry Lee Mueller defines citizen diplomacy as “the concept that, in a vibrant democracy, the individual citizen has the right—even the responsibility—to shape foreign relations, as some NCIV [National Council for International Visitors] members express it, ‘one handshake at a time’ (2009, 47)”. The term is also referred to as “track two diplomacy” by Berridge and Lloyd (2012, 368) and “people-to-people” diplomacy by the DiploFoundation (2024). In addition to this idea of “shaking hands” with foreign nations, Pauline Kerr and Geoffrey Wiseman define citizen diplomacy as “the engagement of individual citizens in private sector programs and activities that increase cross-cultural understanding and knowledge between people from different countries, leading to greater mutual understanding and respect, and contributing to international relationships between countries” (2013, 346). The Diplo Foundation (2024) adds that “Citizen diplomacy is based on the belief that ordinary people can make a difference in international relations and that by building connections and relationships with people from other countries, they can promote mutual understanding and respect.” Therefore, citizen diplomacy can be understood as a process in which individuals—rather than governments—build international personal and cultural bridges. This framework provides a lens for considering how the performance of corridos, particularly by Los Tigres, operate as tools for building these bridges.

This article situates U.S.-Mexico border culture within the development of Borderlands Theory, followed by an overview of the evolution and cultural significance of the corridos style and an introduction to Los Tigres del Norte. I then explore the ways in which Los Tigres’s performance of corridos may influence public political opinion. Los Tigres’s transnational audience and wide reach engenders a specific form of cultural diplomacy based on performance. Concerts and performances of their corridos transcend its entertainment value to carry a fundamental message of transnational understanding and respect. Drawing from sociologist William Danaher’s (2010) concept of music as a “vehicle for social change,” I frame their support of the Democratic ticket in the 2024 U.S. presidential race as an important moment to evaluate their potential effectiveness in developing cross-cultural understanding and influencing political action from the audience. Highlighting the increasing political involvement of performers in the Latino community, I encourage the continued performance of these political corridos and advocate future research to continue exploring artistic mediums and their efficacy in strengthening connections and understanding between nations and their cultures.

THE U.S.-MEXICO BORDER

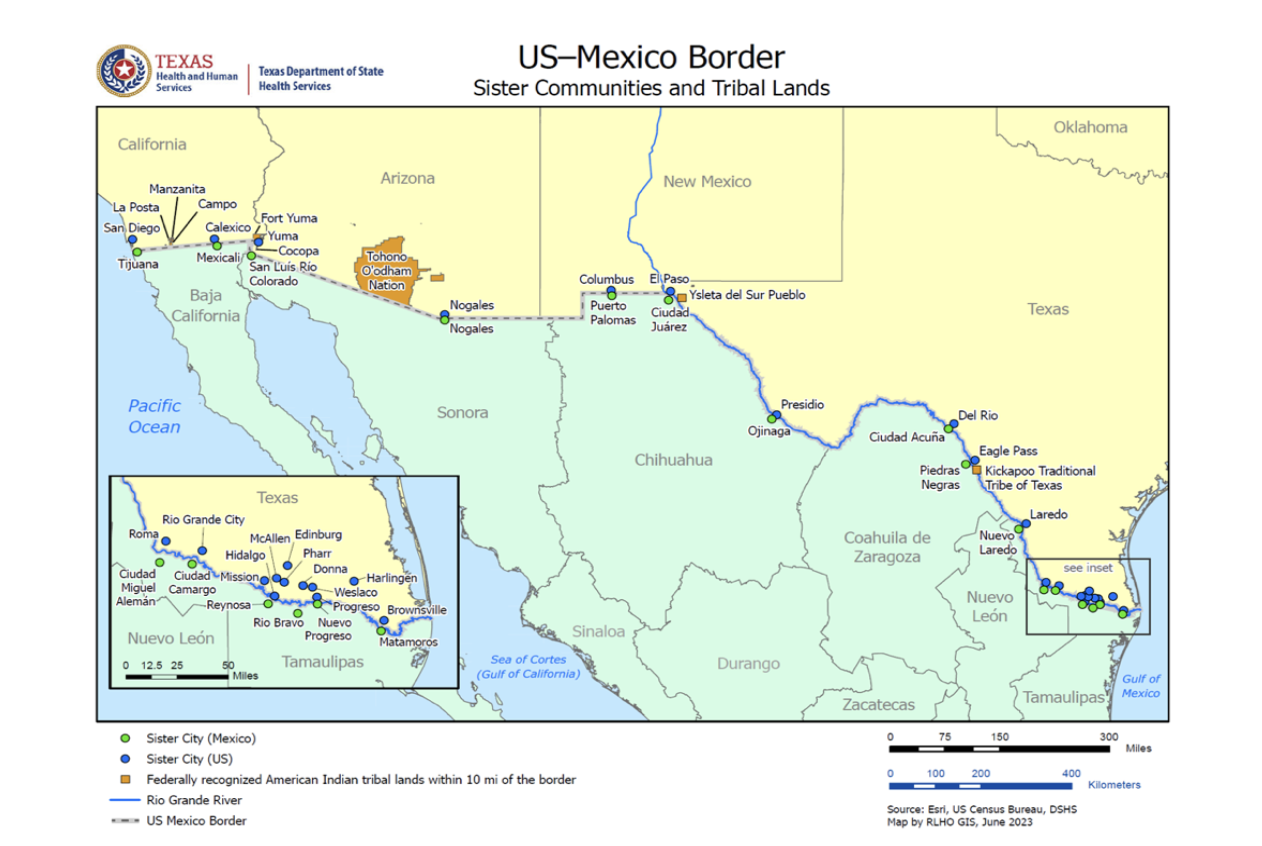

The U.S.-Mexico border spans nearly 2000 miles, separating four U.S. states and six Mexican states. Most of our border today was established after the Mexican-American War, through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, turning over 55% of Mexico’s land to the U.S.

In addition to the different nations on each side of the border, culture and economics are juxtaposed in striking ways, as described by Mark C. Edberg:

In a region contested since before the Mexican-American War, there remains a juxtaposition of visible power exemplified by the infamous border wall, the ubiquitous presence of the border patrol, the drug-war-related military presence, and the relative wealth and proliferation of retail outlets on the U.S. side, set against the constant fluidity of the region—families living on both sides of the border, the daily cross-border traffic, the flow of immigrants and labor, and shared media and culture. On the Mexican side, there is the jarring co-existence of dusty, dirt-poor colonias (neighborhoods), and the proliferation of maquiladora factories, against the sequestered wealth of Mexican ruling families, the sometimes-garish, gated, and festooned homes of narcotraffickers, and the glitzy PRONAF business district in violence-ridden Ciudad Juárez (2011, 70–71).

Despite the economic dominance of the United States, the dominant culture along the border remains Mexican (Azcona 2024). These stark contrasts engendered by this political border make it a productive source for thinking and developing Borderlands Theory as an area of study, influencing research on other liminal territories (Alvarez 1995, 449; Anzaldúa 2022). Martha Sánchez discusses the development of this theory, stating it was born “out of a necessity to rethink and transform borderlanders as political subjects with critical sensibilities that will explain and eventually resist oppression” (2006, 5–6). In this way, the borderlands give rise to cultural spaces where traditions and identities intersect and evolve.

Figure 1: Map of the U.S.-Mexico border, with sister communities and tribal lands highlighted. Image from the Texas Department of State Health Services website.

CORRIDOS

Originally taking form in the mid-19th century with roots in Spanish romance, corridos were performed in rural areas of northern Mexico. Corridos spread orally, relaying current events in towns and between towns, becoming especially popular during the Mexican Revolution of 1910–1920 (Avila 2013; Azcona 2024). They typically glorify a Mexican protagonist, either fictional or nonfictional, telling the story of their conflicts with opposing forces. Some examples of nonfictional corridos heroes and bandits include Gregorio Cortez (e.g., “El Corrido de Gregorio Cortez”), Pancho Villa (e.g., “La Persecución de Pancho Villa”), and Jacinto Treviño (e.g., “El Corrido de Jacinto Treviño”) (Edberg 2011, 70; Paredes 1976, 31–32).

Corridos use a poetic style, often accompanied by guitars and accordions, and can sound texturally similar to waltzes or polkas. Most corridos are in strophic or binary form. They typically have six stanzas and use an AABAAB form, though some other binary structures exist. This lack of sectional variety serves to preserve the song’s narrative flow (Alviso 2011, 70). In the 1920s and 1930s, corridos used small instrumentation, typically two singers with one or two guitars (sometimes harp), which reflected the practical realities and affordability of traveling musicians (Alviso 2011, 63). Since then, corridos have expanded to include a variety of instruments, including those of norteño, mariachi, and banda ensembles (Alviso 2011, 64). In turn, this led to an adoption of their styles. Today, the conjunto instrumentation (button accordion, bajo sexto, electric bass, and drum set) is the most prominent in corridos—including those by Los Tigres del Norte, who occasionally incorporate saxophone.

Attracted by the U.S.’s economic expansion after World War II, the Mexican-origin population in U.S. border states grew rapidly (Ganster and Lorey 2016, 151–54). This led to social and cultural conflicts and violence between Mexican American migrants and the Anglo population. With the Chicano movement of the 1960s and 1970s, corridos evolved into a tool for protest and unity, telling these stories of oppression and resistance (Avila 2013; Ganster and Lorey 2016, 156–162). These stories often detail events or the lives of migrants facing various troubles in the United States, including economic hardships, racial violence, and victimization due to perceived cultural inferiority. For example, Rumel Fuentes’s “Corrido de Pharr, Texas” tells the story of the Pharr Police Riot of 1971, which started as a protest against the city’s frequent police brutality against the Latino population, followed by police attacking the protesters and escalating into a riot, resulting in the death of a bystander (Rumel Fuentes - Topic 2020; Robles 2021):

Hay cuatro o cinco testigos

De mucha brutalidad.

Se oyen tritos en las celdas

Que es una barbaridad.

Una protesta calmada

En contra los policías,

La gente los denunciaba

Por cosas que se sabían.

Mataron a Poncho Flores,

Fue un policía de Pharr;

A un hombre empistolado

No se le pueder confiar.

(From Fuentes 2009)

There are four or five witnesses

Of much police brutality.

You can hear screams in the cells;

This is barbarism.

A calm protest

Against the police,

The people denounced them

For things they knew about.

They killed Poncho Flores,

It was a policeman in Pharr;

A man who wears a gun

You cannot trust.

The stories told within borderlands corridos unveil a side of history many find unfamiliar—from the silenced and oppressed. Social conflicts, then, become apparent in the performances of the stories embedded in their lyrics. Texas-Mexican folklore and corridos, as Sydney Hutchinson argues, grew as a response to ethnic-Mexican social oppression which quickly became a “‘tradition of resistance’ to Anglo domination,” (2011, 42).

Los Tigres del Norte, originally established in Rosa Morada, Sinaloa, Mexico, exemplifies the performance of corridos as resistance. Three brothers—Jorge, Hernán, and Raul Hernández—and their cousin Oscar Lara established the group at a young age. As teenagers in the 1960s, they moved to San Jose, California to advance their music careers. Since then, they have reached an international audience and helped define multiple genres of Mexican music since the 1970s, including modern narcocorridos (corridos that focus on illegal drug trade) and Pacific norteños (norteños influenced by the harsh sound of Sinaloan banda music). Another one of their corridos, “La Jaula de Oro” (“The Cage of Gold”), tells the story of an undocumented immigrant, alludes to the United States as a “golden cage,” and expresses the loss of identity and feeling of captivity experienced by Mexican American migrants who move to the U.S. in hopes of economic prosperity for their future generations.

¿De qué me sirve el dinero

Si estoy como prisionero

Dentro de esta gran nación?

Cuando me acuerdo hasta lloro.

Aunque la jaula sea de oro,

no deja de ser prisión.

(From Los Tigres del Norte 1984)

How does money serve me

if I’m like a prisoner

In this great nation?

When I remember this, I cry.

Although this cage is made of gold,

it’s still a prison.

The protagonist wants a better life for his family, yet his children do not grow up speaking Spanish. Los Tigres del Norte perform this corrido to give voice to those migrants who feel their ancestry was overthrown by Anglo culture, establishing resistance against the eradication of identity engendered by a politically constructed border. In essence, this corrido seeks to resist the loss of identity through vocal and poetic expression.

CORRIDOS THROUGH THE LENS OF CITIZEN DIPLOMACY

Corridos build a sense of identity for individuals and groups which transcend social, historical, and geographical boundaries. For example, Mark Edberg (2011, 77) highlights the testimony of a Latino prisoner who credited Chicano Movement corridos for strengthening solidarity amongst other Latino inmates. This experience mirrors the historic unifying role of corridos during the Mexican Revolution. Music also serves as a marker of cultural identity that engenders social forms of expression through dance and performance (Sánchez 2006, 5).

Sánchez details the cultural effects of corridos, stating that borderlands music, including corridos, has the power to “link many Mexican Americans and immigrants, both documented and undocumented, to their ‘Mexicanness’” (2006, xvii). She expands on these effects to describe the political influence culture can have: “The political borders between Mexico and the United States are continuously challenged, deconstructed, and broken down by the physical movements and cultural expressions of Mexican migrants. Such transnational cultural expressions and performances indicate a certain level of autonomy among migrants” (2006, 44).

Through contesting political borders through culture, the agency of performers to resist loss and erasure of identity demonstrates the capacity of corridos to challenge public politics. While scholars have emphasized the transnational significance of corridos, some, such as Sánchez (2006) and Edgerg (2011), have tended to frame the genre’s influence as reflective rather than active. With performances of their music, Los Tigres del Norte actively engage in transnational politics, as opposed to the idea that the genre merely takes on issues of cultural identity passively. This “engagement” by Los Tigres reflects the practice of citizen diplomacy, with the band members as the “ordinary people” cultivating these international relationships through building transnational understanding and respect. Viewing the performance of corridos in geopolitical contexts through the lens of citizen diplomacy helps us understand its role as an active contributor to U.S.-Mexico relations. Most recently, the band’s involvement in the 2024 U.S. Presidential Campaign demonstrates their most outspoken partisan support.

THE 2024 U.S. PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN

Since 2016, Los Tigres have verbally supported Democratic Party candidates during U.S. presidential elections, including the most recent 2024 election between Donald Trump and J. D. Vance (Republican) and Kamala Harris and Tim Walz (Democrat). Previously, they interacted with both the Republican and Democratic party, such as the bipartisan involvement of Congress when they headlined the concert at the 2013 Camino Americano: Concert and March for Immigrant Dignity and Respect rally in Washington, D.C. (Montgomery 2013).

On October 31, 2024, five days before the presidential election, Los Tigres performed at a Harris-Walz rally in Phoenix, Arizona for a crowd of over 7,000 people (Carranza 2024). One of their corridos performed, “De Paisano a Paisano,” tells of a Mexican migrant worker who loves his home country yet opposes the idea of national borders and addresses the discrimination and exploitation migrants endure in the U.S. while pursuing a better future for their families:

De paisano a paisano.

Antes de seguir cantando,

Yo le pregunto al patrón:

¿Quién recoge la cosecha?

¿Quién trabaja en la limpieza

hoteles y restaurants?

¿Y quién se mata trabajando en construcción?

Mientras el patrón regaña,

tejiendo la telaraña,

en su lujosa mansión

Muchas veces ni nos pagan,

Para que sane la llaga como sale envenenada,

nos echan la inmigración.

(From Los Tigres del Norte 2000)

From countryman to countryman,

Before continuing singing,

I ask the boss:

Who reaps the harvest?

Who works in cleaning

hotels and restaurants?

And who is killed working in construction?

While the boss scolds,

weaving the web

in his luxurious mansion.

Many times they don’t even pay us.

And so the open wound might burn like poison,

immigration kicks us out.

The performance of this song resonated deeply with the audience and their identities. The lines “¿Y quién se mata trabajando en construcción?” and “En una misma nación” elicited cheers from the crowd (MSNBC 2024, 0:36:47–0:37:27). A Mexican immigrant and audience member expressed the performance’s effect on culturally specific resonances and emotional impact:

Los Tigres del Norte, for many years, have sung songs that we can identify with, especially those of us living in this country…When you hear the word “paisano” and listen to the song it makes you want to cry…The music reflects everything that we’ve lived through, from discrimination, to the opportunities, or the persecution we’ve endured. (Carranza 2024)

Whether or not the protagonists in the songs are real, they are made real through their precise expression of what millions of immigrants in the U.S. are currently experiencing, such as the exploitation of migrant workers, evident through numerous reports and investigations of wage theft, unsafe housing and working conditions, sexual abuse, retaliation for complaints, lack of legal protections, and much more (Business & Human Rights Resource Center 2023, 2025; Centro de los Derechos del Migrante 2018, 2020; Human Rights Watch 2001; Vásquez 2025; Woodmansee 2023). It is as if these songs represent the stories of their life—many immigrants can express the same lines of these songs from their perspective as if telling a part of their autobiography. Therefore, each song’s story functions as a collective consciousness representing millions of similar stories with a shared message.

The idea of musical performance playing a role in indirect political action is not new. Danaher (2010) refers to music as a “vehicle for social change,” arguing that in free spaces (physical or symbolic areas where the dominant culture can be criticized), cultural identity is formed, thus developing a social movement culture. Once this culture is formed, political activity can be mobilized (Danaher 2010, 816–818). He also highlights the significant role lyrics play in developing a collective consciousness, providing examples such as the utilization of 1950s and 1960s folk and folk-rock music in the antiwar movement of the 1960s (Denisoff 1971), hillbilly music by depression-era southern textile workers (Roscigno et al. 2002), and a song written for the 1929 Gastonia textile mill worker’s strike during the labor movement (Roscigno and Danaher 2004). Through their relatable and (often violently) truthful lyrics, Los Tigres and their corridos were a voice for immigrants during the Chicano movement and remain a voice for them today.

Los Tigres address their fans, calling for their action to vote for and support a political party platform with focuses on immigrant rights, including “Legal Immigration Pathways,” “Keeping Families Together and Supporting Long-Term Undocumented Individuals, including Dreamers,” and “Fast, Efficient Immigration Decisions.” Corridos, in this political incitation, becomes an agitating, collective call to action to those with whom its narrative resonates deeply. For instance, listening to Jorge Hernández, the band’s leader, acknowledge mistreated migrant workers during the “De Paisano a Paisano” performance galvanizes the audience to vote for Los Tigres’ choice of candidate with urgency as the voting time window closes.

This performance was part of Harris’s “When We Vote We Win” concert and rally series, intended to appeal to voters from swing states. Of course, this practice is not new, as politicians have used celebrities, musicians, and influencers to win votes for decades. In this case, Harris intended to use Los Tigres’ appeal to rally votes from undecided Latino voters, who make up a quarter of the Arizona electorate. Organizations such as HeadCount, who partner with music artists at concerts and festivals to register more people to vote, have demonstrated the effect musicians can have on voter turnout. According to their 2024 Impact Report, 78% of people who took action with the organization turned out to vote in the election (HeadCount 2024).

However, Los Tigres were not involved in any of these partnerships, merely present at the rally, asking for political action from the audience.

While Los Tigres chose to engage politically, their participation in a partisan event complicates the boundaries of their agency. This performance fosters a symbiotic relationship between Los Tigres and the Harris-Walz ticket. Los Tigres benefit through increased publicity and outreach—in turn, politicians utilize the band’s influence to build support for their campaign. Whether intentional or not, this develops a deeper symbiotic relationship between voters and the Harris-Walz ticket, with Los Tigres as the diplomatic cultural intermediary. In addition to their role as “La Voz del Pueblo,” delivering messages from the Latino community and immigrants to the politicians, they are assuming a responsibility by the Democratic Party to deliver a message to the public. The band’s political involvement through performance parallels with the practice of citizen diplomacy, bridging the gap in understanding between US Democratic politicians and the culture of Latino immigrants, as well as potentially influencing political activity by their community.

CONCLUSION

It is no surprise that corridos develop a strong sense of shared cultural identity in the Latino community. Additionally, expression through song often emerges as a natural response to oppression and a passion to resist. An epigraph from Anzaldúa’s book (2022, 88) states the Mexican saying, “Out of poverty, poetry; out of suffering, song.” In turn, these forms of transnational cultural expression play a subsequent role, one as a medium for transnational cultural influence. As seen in Los Tigres’s performance at the 2024 Harris-Walz rally, these influences hold the potential to cultivate understanding and respect within a nation and between nations through their music that mobilizes border identities into collective empathy and political motivation. Performers of these corridos are messengers. Joining forces with a diplomatic entity, politician, or other body of international power gives them momentous power and responsibility to reach various audiences and shape international thought.

Yet this case raises important questions for future study. What are the limits of musical diplomacy? How much agency do artists retain once they enter political spaces? Can performances that function as citizen diplomacy directly influence policy, and how effective are they? Can the outcome of the electorate be attributed in part to the musicians? As intermediaries, to what extent are these practices powerful to engender direct change? Hopefully, future research will continue to explore more methods for countries—and their people—to continue making progress “one handshake at a time.”

REFERENCES

Alvarez Jr., Robert R. 1995. “The Mexican-US Border: The Making of an Anthropology of Borderlands.” Annual Review of Anthropology 24: 447–470.

Alviso, Ric. 2011. “What is a Corrido? Musical Analysis and Narrative Function.” Studies in Latin American Popular Culture 29 (1): 58–79.

Anzaldúa, Gloria. 2022. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, 5th ed. Aunt Lute Books.

Avila, Jacqueline. 2013. “Corrido.” Grove Music Online. October 10, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.A2249156.

Azcona, Estevan César. 2024. “Border Music.” Grove Music Online. October 10, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.A2234471.

Blais, André, and Jean-François Daoust. 2020. The Motivation to Vote: Explaining Electoral Participation. University of British Columbia Press.

Berridge, G., and L. Lloyd. 2012. The Palgrave Macmillan Dictionary of Diplomacy. Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Business & Human Rights Resource Centre. 2025. “‘Not Just a Number’: Tracking Migrant Worker Abuse in Global Supply Chains - 2025 Global Analysis.” October 1, 2025. https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/from-us/briefings/migrant-worker-analysis-2025/not-just-a-number-tracking-migrant-worker-abuse-in-global-supply-chains-2025-global-analysis/.

Business & Human Rights Resource Centre. 2023. “USA: Mexican Workers Contracted by LVH Subject to Forced Labour on Watermelon Farms Supplying to Walmart, Kroger, Sam’s Club & Schnucks.” October 1, 2025. https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/usa-mexican-workers-contracted-by-lvh-subject-to-forced-labour-on-watermelon-farms-supplying-to-walmart-kroger-sams-club-schnucks/.

Carranza, Rafael. 2024. “What to Know About Los Tigres del Norte, the Popular Group that Played at Harris Rally.” Arizona Republic. https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/politics/elections/2024/10/31/los-tigres-del-norte-what-to-know-about-pro-kamala-harris-group/75969735007/.

Carrasquillo, Adrian. 2013. “Los Tigres del Norte Perform at Massive Immigration Rally.” BuzzFeed News. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/adriancarrasquillo/los-tigres-del-norte-perform-at-massive-washington-immigrati.

Centro de los Derechos del Migrante. 2018. Recruitment Revealed: Fundamental Flaws in the H-2 Temporary Worker Program and Recommendations for Change. October 1, 2025. http://www.cdmigrante.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Recruitment_Revealed.pdf.

Centro de los Derechos del Migrante. 2020. Ripe for Reform: Abuse of Agricultural Workers in the H-2A Visa Program. October 1, 2025. https://cdmigrante.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Ripe-for-Reform.pdf.

Danaher, William F. 2010. “Music and Social Movements.” Sociology Compass 4 (9): 811–23.

Denisoff, R. Serge. 1971. Great Day Coming: Folk Music and the American Left. University of Illinois Press.

Diplo. 2024. “Citizen Diplomacy in 2024.” September 29, 2025. https://www.diplomacy.edu/topics/citizen-diplomacy/.

Edberg, Mark C. 2011. “Narcocorridos: Narratives of a Cultural Persona and Power on the Border.” In Transnational Encounters: Music and Performance at the U.S.-Mexico Border, edited by Alejandro L. Madrid. Oxford University Press.

Fuentes, Rumel. 2009. “Corrido de Pharr, Texas.” Track 9 on Corridos of the Chicano Movement. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. Originally released on Arhoolie Records. Apple Music.

Galais, Carol, and André Blais. 2016. “Beyond Rationalization: Voting Out of Duty or Expressing Duty After Voting?” International Political Science Review 37 (2): 213–29.

Ganster, Paul, and David E. Lorey. 2016. The U.S.-Mexican Border Today: Conflict and Cooperation in Historical Perspective. 3rd edition. Latin American Silhouettes. Rowman & Littlefield.

Hansen, Ronald J., Stephanie Murray, and Rafael Carranza. 2024. “Kamala Harris Rallies with Los Tigres del Norte to ‘Turn the Page on Donald Trump.’” Arizona Republic. https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/politics/elections/2024/10/31/harris-rallies-with-los-tigres-del-norte-on-halloween-what-to-know/75881149007/.

HeadCount. 2024. 2024 “HeadCount Impact Report.” October 2, 2025. https://www.headcount.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/2024-HeadCount-Impact-Report.pdf.

Human Rights Watch. 2001. “Hidden in the Home: Abuse of Domestic Workers with Special Visas in the United States.” October 1, 2025. https://www.hrw.org/report/2001/06/01/hidden-home/abuse-domestic-workers-special-visas-united-states#6110.

Hutchinson, Sydney. 2011. “Breaking Borders/Quebrando Frontas: Dancing in the Borderscape.” In Transnational Encounters: Music and Performance at the U.S.-Mexico Border, edited by Alejandro L. Madrid. Oxford University Press.

Kaczynski, Andrew. 2013. “Eight Democratic Members of Congress Arrested at Immigration Protest.” BuzzFeed News. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/andrewkaczynski/eight-democratic-members-of-congress-arrested-at-immigration.

Kerr, Pauline, and Geoffrey Wiseman, eds. 2013. Diplomacy in a Globalizing World: Theories and Practices. Oxford University Press.

Los Tigres del Norte. 1984. “La Jaula de Oro.” Track 1 on La Jaula de Oro. Fonovisa Records. Apple Music.

Los Tigres del Norte. 2000. “De Paisano a Paisano.” Track 1 on De Paisano a Paisano. Fonovisa Records. Apple Music.

Mier, Tomás. 2024. “Maná and Los Tigres del Norte Will Perform at Kamala Harris Rallies in Nevada and Arizona.” Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/mana-tigres-del-norte-will-perform-key-kamala-harris-rallies-nevada-arizona-1235143473/.

Montgomery, David. 2013. “Los Tigres del Norte Sing ‘The Real Stuff’ at Immigration Rally.” Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/los-tigres-del-norte-sing-the-real-stuff-at-immigration-rally/2013/10/08/c3a26a84-304f-11e3-bbed-a8a60c601153_story.html.

MSNBC. 2024. “LIVE: Kamala Harris Holds Rally in Battleground Arizona, Featuring Los Tigres del Norte | MSNBC.” YouTube Video, 1:50:50. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PrNtHKZDvzg.

Mueller, Sherry Lee. 2009. “A Half Century of Citizen Diplomacy: A Unique Public-Private Sector Partnership.” The Ambassadors Review.

Paredes, Américo. 1976. A Texas-Mexican Cancionero: Folksongs of the Lower Border. University of Illinois Press.

Paredes, Américo. 1958. “With His Pistol in His Hand”: A Border Ballad and Its Hero. University of Texas Press.

Robles, David. 2021. “‘It Was Us Against Us’: The Pharr Police Riot of 1971 and the People’s Uprising Against El Jefe Político.” In Civil Rights in Black and Brown: Histories of Resistance and Struggle in Texas, edited by Max Krochmal and Todd Moye. University of Texas Press.

Roscigno, Vincent J. and William F. Danaher. 2004. The Voice of Southern Labor: Radio, Music, and Textile Strikes: 1929–1934. University of Minnesota Press.

Roscigno, Vincent J., William F. Danaher and Erika Summers-Effler. 2002. “Music, Culture, and Social Movements: Song and Southern Textile Worker Mobilization, 1929–1934.” International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 22: 141–74.

Sánchez, Martha I. Chew. 2006. Corridos in Migrant Memory. University of New Mexico Press.

Vásquez, Tina. 2025. “She Managed to Get a Farmworker Visa. Once in the U.S., She Endured Abuse.” Prism. https://prismreports.org/2025/09/24/women-h2a-visa-farm-workers-migrant/.

Waldfogel, Hannah B., Andrea G. Dittmann, and Hannah J. Birnbaum. 2024. “A Sociocultural Approach to Voting: Construing Voting as a Duty to Others Predicts Political Interest and Engagement.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121 (22). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2215051121.

Woodmansee, Sylvia. 2023. “Invisible Hands: Forced Labor in the United States and the H-2 Temporary Worker Visa Program.” California Law Review. https://www.californialawreview.org/print/invisible-hands.