The Gondang’s Voice: An Excerpt Dialogue with Aliman Tua Limbong about Music for the Toba Batak Mangongkal Holi Ritual in North Sumatra, Indonesia

Edy Rapika Panjaitan

PhD candidate in Interdisciplinary Arts

Ohio University

ep516922@ohio.edu The air in Sianjur Mulamula carries a kind of density that originates not only from the high mountain mist, but also from centuries of memories from the inhabitants of the village. The beauty of Sianjur Mulamula is surrounded by the volcanic crater lake Toba on Samosir Island in North Sumatra, Indonesia. It is here, among the ridges of the Samosir Island, where Batak[1] myths trace their footprints to their ancestral origins on the sacred mountain, Pusuk Buhit. The gondang sabangunan, also known as gondang bolon, is a traditional musical ensemble that still resounds—sometimes faintly and other times powerfully. Despite the passage of time, this ensemble is a clear reminder of the strength of the Toba Batak. Almost 10,000 miles away from Sianjur Mulamula at my university in Athens, Ohio, I became acquainted with Aliman Tua Limbong through this virtual interview.[2] He was a well-respected and accomplished pargongsi (a gondang musician) who owned and led the Sianjur Mulamula gondang ensemble.[3] As we spoke, a gentle rainfall could be heard, providing a peaceful backdrop to his words. The landscape surrounding his house is filled with beautiful hills, mountains, a waterfall, and acres of rice fields, not so far from lake Toba. This brief but concise interview was a window into the rhythms that Aliman has carried with him throughout his life, as if they were the very heartbeat of Toba Batak philosophy, music and ritual, and the intertwining ideas of tradition and cultural heritage.

As a Toba Batak man and a fluent speaker of the Toba Batak language, I am currently writing my Ph.D. dissertation at Ohio University on the ethnographic study of the mangongkal holi, the ancestral bone exhumation ritual in Sianjur Mulamula village. My research employs a hybrid ethnographic methodology to conduct, document, and analyze the musical and performative elements of the mangongkal holi in Sianjur Mulamula, Samosir Regency, North Sumatra, Indonesia. Through this approach, I aim to preserve the gondang repertoire and to examine its performative, cultural and philosophical dimensions. This interview has become a vital part of my research, offering deep insights into the life experiences of gondang musicians and their enduring role in perpetuating the musical dimension of the mangongkal holi ritual.

When I asked him what the mangongkal holi meant to him, Aliman paused, his eyes narrowing as though he were sifting through decades of both memory and inherited wisdom. At 62 years old, he tried to paint a picture of this ancient journey. “Mangongkal holi is how we remember our ancestors,” he began. The tone of his voice carried the cadence of someone who has repeated this truth countless times, but never ever casually. “The Toba Batak people recognize that they exist today because of fathers, grandfathers, and the previous generations that we call sundut. This ritual is a declaration that we honor them.” But the memories of ancestors alone are not enough. It is the enactment of the mangongkal holi ritual that binds families together by weaving fragmented branches of lineage into a cohesive whole. When ancestral remains are raised from the earth, it is not only an act of reverence but also one of unity. Across three generations, an ancestor is called ompung; seven generations and above, oppu. These ancestors expand into a vast collective, the parsadaan, that guards the living.[4] Aliman was at pains to make it clear that the mangongkal holi ritual is believed to bring blessings—meaning greater prosperity, protection, and the emergence of offspring who will “bring honor” to the family. He quoted the Batak proverb, “sai unang ma nian tarpatiptip songon babani solup, sai marjunjungan ma songon napuran”—the journey of a family should not remain flat like a bamboo mat but, rather, must have someone who upholds its honor and leads it forward. For the Toba Batak, the core of life is built upon three distinct pillars: hagabeon (offspring), hamoraon (wealth), and hasangapon (honor). Among these, hasangapon is the most vital, as it sustains and gives meaning to the other two. This philosophical merit has long been the driving force behind the continuation of the mangongkal holi ritual.

His historical knowledge and childhood recollections painted a vivid picture into the earlier practice of mangongkal holi. Before Dutch and Japanese colonial influences altered burial traditions, kings and affluent families interred their dead in paromasan—impressive stone tombs crafted either as batu singkam (jar-shaped stone graves) or batu sada (sarcophagi). In subsequent years, communal cemeteries known as parholian were erected, but the exhumation ritual was never an everyday affair. On the contrary, it required abundance in offerings: water buffaloes to be slaughtered, granaries filled with rice, and wealth to be displayed. “Margondang (to perform gondang) was rare,” he said. “Only the rich, the famous, those with water buffaloes and land could afford it.” When a family actually decided to exhume bones, they began with marhusip, intimate whispering meetings among kin. After much deliberation, they sought the expertise of the sititi ari, ritual diviners called datu who were invited to select an auspicious day. Once agreed there would be the sukun sukun marsaripit—detailed discussions of etiquette, invitations, and dividing up the responsibilities of all involved. The ritual would almost certainly require the approval of raja (the head of the patrilineal kinship group called marga). In Sianjur Mulamula, these were called manggalang raja. The Toba Batak raja would traditionally bless the event with food offerings, and in so doing formally authorize the ceremony. Without this, the ritual could not proceed. Today, as Aliman lamented, the practice has grown casual; this approval is no longer demanded or required.

“What is gondang if not the very breath of the ritual?” Aliman posited, his words carrying more reflection and rhetoric than inquiry. In the past, no Toba Batak ceremony was complete without the presence of gondang. The ensemble itself is elaborate, consisting of the taganing—a set of five single-headed, conical, tuned drums—along with two bass drums, four suspended gongs, a sarune (double-reed aerophone), and a hesek (a metal or glass concussion idiophone played with a stick or rod). More than simply accompanying the ritual and tortor dance, the gondang served as a medium to promote dialogue between the living, the ancestors, and the divine. Over time, the role of this ensemble has shifted—transforming into entertainment and preserved primarily as a symbolic marker of cultural heritage. He explained that each true gondang carries intent. For instance: Hasahatan gondang expresses requests to Mula Jadi Na Bolon,[5] the Batak high god, to be channeled through the hula-hula (wife-givers) whose blessings sanctify an event. Mangalahat horbo, the slaughter of a water buffalo, acts as a sacrifice that embodies thanksgiving to the family and participants in the ritual. Without gondang, the ritual loses its dialogical essence—the conversation between music, dance, people and the overarching spiritual realm. I asked Aliman whether he thought the younger generation understood these meanings. He was pensive and his answer somewhat jarring: “Now [the young people] only hear rhythm. They raise their hands and dance, but they don’t understand the soul of the gondang.” With a heavy heart he sighed. “Our ancestors gave us music from the divine. We are supposed to preserve it, not dilute it, but they now perform the popular song Stecu-Stecu in funerals, which to me seems absurd.”

For Aliman, the relationship between gondang and tortor dance is not one of accompaniment but, rather, one of communication. The gondang speaks, the panortor (dancers) answer. Each movement—the position of the hands, the opening gestures, the waving movements—are the embodiment of the philosophy of respect, dignity, and identity. “When a Toba Batak person dances,” he said, “they bow first. They acknowledge the other participants, then open their hands. THAT is pride. That is identity. In displaced diasporas overseas, when Batak people dance, they do not want to be followers—they want to be leaders. That is embedded in the movement of this dance.” However, to execute such communication demands mastery from the gondang musician, the pargongsi. They must read the aura of dancers, sensing whether the energy requires moderation, flamboyance, or even acceleration. Sometimes the gondang shifts mid-performance, two songs combining to sustain the dancers’ vigor. It is this, he said, that is artistry—never written down as notation but inscribed in memory and soul.

As our dialogue deepened further, Aliman’s voice often carried a frustrating melancholy. He predicted that within the next few years, the established system of mangongkal holi rituals could vanish. The heady concoction of economic pressures, religious influence, and the rise of modern instruments like keyboards would wear down the traditions of this ritual. “Now [the musicians] play keyboard instead of gondang sabangunan. The sound may represent what this music once was, but the spirit does not. The gondang’s essence cannot be distilled.” He critiqued the casual treatment of musicians today. Pargongsi were once highly respected and provided with special houses and meals during rituals. With the predominance of common commercial catering services, musicians are served in the same way as the other guests. “We are still respected to some extent, but this respect has eroded,” he admitted. The passing of gondang knowledge, too, falters. To this day, no formal training centers exist in this region. The young ones learn from YouTube videos, imitating sounds but sadly not absorbing the spiritual depth of the music. “Without understanding essence, this culture will not go in any depth. It will only be sound, and not spirit.”

Beyond the music itself, Aliman contemplated the deeper meaning that underpins mangongkal holi. He explained that families often turned to ritual only in response to difficulties they were having—whether this was financial hardship, conflict among siblings, or growing distance between relatives. By their very nature, rituals compel everyone to come together, helping them face divisions within the family, and providing solutions to work toward reconciliation. He explained that while ancestors are honored, the participant’s prayers are ultimately directed to Debata Mula Jadi Na Bolon (the most revered Batak deity) for blessings. And yet, he reflected, there is no distinct ritual for this deity—only the recognition that honoring ancestors is itself a path to divine grace. He spoke of the visible and invisible worlds of laelae gondang. It serves as a plea to the Debata Mula Jadi Na Bolon, imploring that the offerings be received even in spite of flaws or shortcomings of the family. Indeed, each tribute is expected to carry a clear purpose rooted in ancestral custom, yet performed through human actions—such as the sacrifice of a water buffalo—so that a family can live with neither excess nor disparity. Thus, through laelae gondang, participants seek divine guidance and pray that the ritual may still be embraced as worthy, even in spite of these inevitable imperfections. The ritual acknowledges the spirits of mountains, households, and tondi (human souls). It is respect, not worship, that is the guiding principle. The Toba Batak people acknowledge that everything—seen and unseen—possesses power.

When I asked what fondness he found in being a gondang player, Aliman smiled. “This is my life,” he said. Gondang carried him far from Samosir, to Java and Jakarta, granting him recognition he never imagined. “I might not have completed law school, but as a pargongsi, I have received honors. That is my pride.” Yet this heavy role carries inevitable burdens. To be a gondang musician is to embody honesty; deception is forbidden. Agreements over performance fees must be decided with transparency, invitations must be respected, and rituals must be served faithfully. The pargongsi are both at once artists and moral figures. To top this all off, there is also the constant struggle against impending marginalization. “When the catering comes (a commercial culinary service), we are forgotten,” he said. “Before, we were given special houses and meals (which traditionally the suhut—the host and neighbors cook and serve food together). Now, we queue with everyone else.” His voice had elements of both resignation and defiance. Toward the end of our conversation, his reflections turned to the future. He criticized the local government of Samosir regency for promoting tourism without adequately supporting culture. “They build glass bridges, waterfront cities. People come once, twice. But [tourists] return to Bali because of the strength of cultural support they receive. A nation is only great if it can truly uphold culture.” He recalled speaking before Indonesia’s former Minister of Education, Nadiem Makarim, urging that Sianjur Mulamula be recognized as the Batak origin area, and considered distinct from other regencies in the area. In 2024, he was honored as one of the foremost musicians in his field, and yet he still felt inconsistencies with such cultural recognition. His plea was simple: establish training centers, museums, and support systems so that Batak youth would be able to inherit their ancestral arts. Without such efforts, gondang risks becoming a hollow spectacle, stripped of its fundamentally sacred core.

As dusk began to fall, the sounds of distant gondang rehearsals drifted into our conversation space. I asked Aliman what gondang ultimately meant to him. He closed his eyes for a moment, then answered softly: “Gondang is memory. Gondang is communication. Gondang is dignity. Without gondang, the Toba Batak people cannot speak to their ancestors, cannot bind their families, cannot show who they really are.” In his words, I heard both a kind of simultaneous mourning and hope—a lament for the fading away of sacred forms, but also a call for renewal. The extinction of gondang may be threatened by the advent of electronic alternatives, from modernity and forgetfulness with the passage of time. Still, as long as musicians like Aliman Tua Limbong strike the taganing, for as long as the sarune cries across Sianjur Mulamula, the ancestors are not silent. Their gondang still speaks.

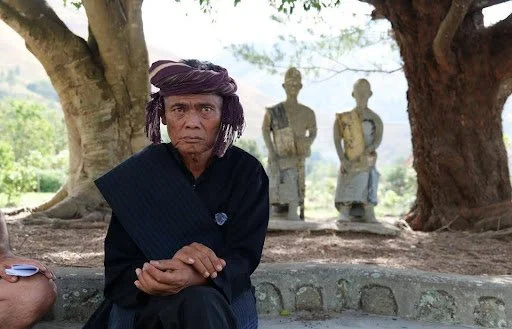

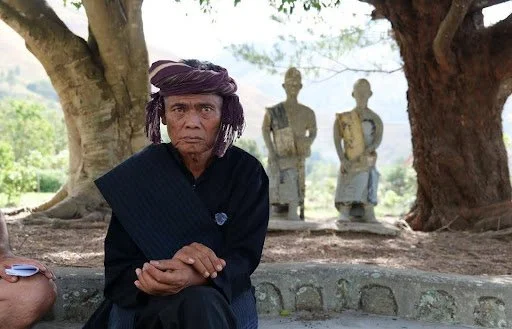

Figure 1. Aliman Tua Limbong, pargongsi Sianjur Mulamula group, located in Si Raja Batak site, Huta Urat (Urat Village), Sianjur Mulamula District, Samosir Regency, North Sumatra, Indonesia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am deeply grateful to the late Amang Aliman Tua Limbong for generously sharing the voice of his gondang journey. His passing on September 14, 2025, marks a profound moment of remembrance and this work stands as a tribute to his musical legacy. I also sincerely thank Amang Johnny Siahaan and Amang Thompson HS for their invaluable assistance during this interview conducted on August 4-5, 2025.[6] This musical journey has provided me with a transcendental discovery of gondang sabangunan and its most important figure, Aliman Tua Limbong.

REFERENCES

Limbong, Aliman Tua. Virtual interview with author. August 4-5, 2025, Sianjur Mulamula Village, Sianjur Mulamula District, Samosir Regency, North Sumatra, Indonesia.

NOTES

[1] The Batak people consist of six subgroups, Toba, Simalungun, Angkola, Mandailing, Karo, and Pakpak. These subgroups share some language traits and cultural similarities, but they all maintain distinct social, linguistic, and ritual identities.

[2] Aliman Tua Limbong, virtual interview by Edy Panjaitan, Sianjur Mulamula Village, Samosir Regency, North Sumatra, Indonesia, August 4-5, 2025.

[3] The Gondang Sianjur Mulamula group is eponymously named after the village where Aliman was born. Aliman began playing gondang music in 1987, after leaving law school in Medan due to illness. Following his parents’ advice to return home and marry, he eventually devoted himself to music and founded the ensemble in 1988. Around 1999, his ensemble was established to begin receiving invitations to perform for ritual clients.

[4] Others note that ompung is a general term for ancestors across generations, whereas ompu or oppu carries a more sacred, elevated status and is used to honor specific revered figures or collective ancestral spirits—such as Oppu Mula Jadi Na Bolon or Oppu Parsadaan.

[5] Most Toba Batak people are Christians or Catholics and refer to God as Debata Mula Jadi Nabolon. Aliman, though a Catholic, used this name for God—the same name revered in Parmalim, the indigenous Batak religion.

[6] I am very fortunate to discover the late Aliman Tua Limbong, the leader of the Gondang Sianjur Mulamula Group. The interview and gondang performance of Sianjur Mulamula group were also made possible through the assistance of Johnny Siahaan (photographer/videographer) and Thompson Hs (Batak opera artist/writer).