Hypothetical Concert: Presence, Absence, and the Politics of Iranian Musical Performance

Mohammad Moridvand

Master's student, Ethnomusicology

Art University of Tehran

mo.morid1997@gmail.com

INTRODUCTION

In December 2024, a musical event entitled “Hypothetical Concert” was held in one of Iran’s historic caravanserais, featuring the vocalist Parastoo Ahmadi accompanied by piano, drums, electric guitar and bass. Unlike conventional performances, this concert took place without the physical presence of an audience. The absence of an audience did not imply a live broadcast or the presence of online viewers; rather, Ahmadi announced on her Instagram page the exact time at which the performance video would be uploaded, thereby inviting listeners to watch the pre-recorded concert on YouTube at a designated time. The title “Hypothetical Concert” itself carries a certain ambiguity. When I first encountered this title, I asked myself: how can a concert be “hypothetical”? Upon viewing the performance, however, I realized how the prohibition against women singing in Iran had given rise to this term and to the peculiar conjunction of the words “concert” and “hypothetical”. It was “hypothetical” insofar as it was a live concert with an audience, not a livestreamed event. Yet, the behavior of audiences in digital spaces, such as the concert’s extensive viewership on YouTube within the very first hours of its release, and the wide circulation of clips from the performance on Instagram, contributed to its sense of “liveness” rather than to its imagined or hypothetical qualities, pushing its viewership to 2.5 million.

Ahmadi’s statement regarding the “Hypothetical Concert” transformed it from a merely musical Performance into a site of struggle between the state and the people [1]. Through the prohibition of female singing, the state has effectively erased women vocalists from musical activity. This enforced silence and near-total absence of women’s voices in music production after the Revolution is striking, particularly given its sharp contrast with the sonic landscape of the Pahlavi era (Siamdoost 2017, 3). Ahmadi’s decision to perform under such conditions in Iran, appearing with optional dress and performing songs such as “Mara Beboos” (Kiss Me) and “Az Khoon-e Javan?n-e Vatan” (From Our Youth’s Blood), both protest songs from different historical and political moments, resulted in legal action against her. Following the concert, the Judiciary of the Islamic Republic of Iran initiated criminal proceedings against Ahmadi and her collaborators for staging a concert without official authorization and for disregarding the regulatory framework of performance (namely, the ban on female singing and the mandatory hijab). Ahmadi and two accompanying instrumentalists were arrested; her Instagram page was blocked; the caravanserai that hosted the event was sealed; and several officials within the Cultural Heritage Organization were dismissed from their positions.

Ahmadi’s performance was not simply a pre-recorded concert. By virtue of its timing, amid the social uprisings that followed the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement, it became an act of protest. The “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement, sparked by the death of Mahsa (Jina) Amini as a result of compulsory veiling, gave rise to one of the largest social movements in contemporary Iran. Her statement invoked notions of freedom, social justice, and drew attention to the ban on women’s singing in spaces where men are allowed to perform but women are prohibited, whether in concert halls or any other venues with an audience. Yet what sets this performance apart from other acts of protest is precisely its mode of presentation: its staging in the “absence” of an audience.

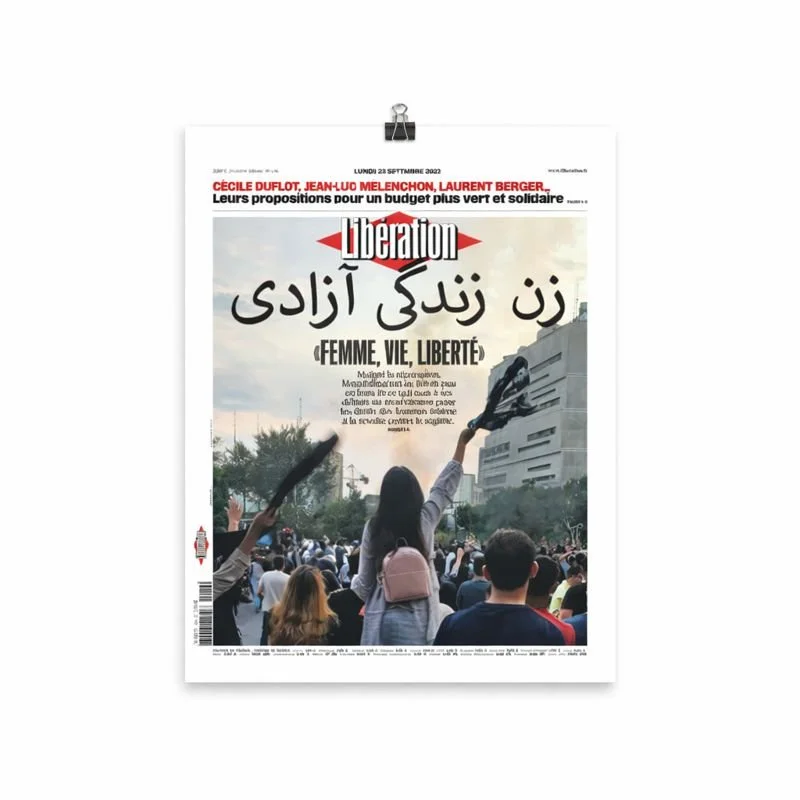

Figure 1: "Woman, Life, Freedom" on the front page of French newspaper Liberation.

This study, by focusing on the notion of the “Hypothetical Concert”, seeks to interrogate the traditional boundaries between performance and audience presence. The theoretical framework of this research is grounded in Martin Heidegger’s philosophy of presence and absence. This framework enables us to understand the “Hypothetical Concert” not only as a musical act, but also as a musical-philosophical phenomenon in which the absence of the audience itself becomes the ground of a different mode of presence.

A concert, by definition, is a public performance of music or dancing. (“CONCERT Definition & Meaning - Merriam-Webster,” n.d.). By contrast, the qualifier “hypothetical” relocates it into the realm of imagination.The central question of this study arises from the necessity of this absence. The site of performance, the stage arranged with instruments, chairs, lighting, and even the applause of at the beginning and end, constitutes the phenomenon of “being at a concert.” But if no audience is present, what becomes of the essence of the performance itself?

RETHINKING THE CONCEPT OF THE CONCERT

In the traditional definition of a concert, the physical presence of an audience is regarded as a necessary condition for performance. However, in the digital age and under contemporary social conditions, the meaning of “concert” has undergone significant transformations. With the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, many musical traditions that were fundamentally rooted in oral transmission also turned to online instruction. These transformations were further reinforced by the expansion of platforms such as satellite broadcasting, the internet, and social media particularly for audiences who, for various reasons, were unable to attend performances in person.

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic marked a turning point in rethinking the definition of the concert through the emergence of the “online concert”. In the past, physical presence was considered inseparable to the concert experience, the pandemic disrupted this assumption. Media, in this context, played an undeniable role in enabling new forms of access. Consequently, the physical presence of the audience can no longer be regarded as an absolute precondition for the holding of a concert. The present study, through an examination of Parastoo Ahmadi’s “Hypothetical Concert”, seeks to interrogate the boundaries between live performances with a physically present audience, online concerts, and pre-recorded (offline) concerts. It is difficult to classify Ahmadi’s concert neatly into any of these categories.

Figure 2: A work by Zard Drawing, from the “Sun Girls” series, 2024

The complexity of Ahmadi’s “Hypothetical Concert” lies in the fact that, due to the prohibition on women singing and the broader political and social conditions in Iran, it could not take place as a live performance with a physically present audience. At the same time, it cannot be classified as an online concert, since the audience did not experience it simultaneously; viewers did not listen or watch at a single, designated time. While it might superficially resemble an offline (pre-recorded) performance, Ahmadi’s musical actions prevent it from being considered truly offline. These actions are evident at the start of the program, when she energetically calls her band members and, with visible excitement, engages in a conversational greeting with her audience, saying: “Tonight, my colleagues and I have a live performance for you.” Her insistence on presenting a live performance for her audience, despite their absence, challenges conventional classification.

To navigate this dilemma, we can draw on Christopher Small’s perspective. For the audience, the concert is neither online nor offline. Rather, it is experienced as a live event from which they are politically excluded. Both performers and audience members are compelled to see and hear one another only through imagination. In this form of performance, the audience is absent both physically and virtually, while the artist proceeds as though the audience were present. Christopher Small emphasizes that music is more than a noun; it is an action, a verb: to music. He introduces the concept of “musicking”, understanding its meaning as embedded in the relationships established among participants during a performance (Small 1999, 11–13). Following Small’s framework, we can view the performance not as contingent upon audience presence whether physical, online, or offline but as a musical action in its own right.

From this perspective, Ahmadi’s presence at the caravanserai can be seen as a musical act, and the absence of her audience in the Hypothetical Concert can be understood merely as an alternative form of participation. Moreover, the imagined presence of the audience in Ahmadi’s concert is accompanied by moments of fictional interaction between herself and her listeners, further reinforcing the relational and participatory nature of the performance.For example, during her performance of “Mara Beboos” (Kiss Me), when the microphone is on the verge of falling, she smiles into the camera as if her audience were right there in the caravanserai with her.

Figure 3: Parastoo Ahmadi greets absent audience in her performance concert in Iran, on Dec 11, 2024.

Even at the end of the piece Mara Beboos (Kiss Me), she smiles and turns back toward the musicians, “The microphone was about to fall.” Throughout the performance, Ahmadi’s gestures and actions bear the traces of an absent audience: she gazes toward empty corners as if addressing listeners, she introduces each of the musicians to the non-existent crowd, and before beginning each song she explains what piece is about to be performed. These musical behaviors operate as signs of an imagined audience, signs that later, through reception, engender presence. Presence here is thus always deferred. My own concerns have consistently been oriented toward the transformations of musical performance in relation to political, social, or even medical circumstances, (such as the COVID- pandemic).

From live performances in physical spaces to the emergence of online concerts, my aim has been to examine these transformations within the context of the relationships between sound, space, and the presence or absence of audiences in Iran. In this process, the rapid expansion of digital technologies and the growing accessibility of the internet in Iran have reshaped the boundaries between performances in public, semi-public, and private spaces. Online platforms, in particular, have opened new possibilities for women, enabling them to circumvent censorship and structural restrictions by sharing videos of their performances, thereby transmitting their voices to audiences beyond the limitations imposed within Iran.

As Laudan Nooshin illustrates, through the example of a performance by Mahsa and Marjan Vahdat in her research: April 2012. On a flat roof in Fin Alley, Tehran, singers Marjan and Mahsa Vahdat perform with a group of musicians. I watch the performance on YouTube.2 It could not have taken place publicly because of the restrictions on solo female singing. And yet here these musicians record themselves in the public- private space of a rooftop with views across Tehran. In some sense this is a public space, since it is potentially accessible to other residents of the apartment block and overlooked by those in other buildings. At the same time, the musicians are somewhat hidden by the architecture and the air conditioning units, and the sounds are fairly contained and unlikely to reach the ears of many But from this semi-hidden physical public-private rooftop space, the music becomes visible and audible (Nooshin 2018, 342).

In contrast to other performances by women in Iran after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, which were typically held in private or semi-private spaces, Parastoo Ahmadi’s performance took place in a public venue. In the study by Swarbrick and colleagues (2024), musical absorption is understood as a complex process that engages the audience’s bodies. The physical presence of listeners plays a central role in enhancing the musical experience, as their bodies interact actively with the music through involuntary movements and oscillations.

In a live concert, everything from purchasing a ticket, finding one’s seat, and preparing for the entry of musicians to the collective applause of the audience generates a simultaneity of attention that itself forms part of the aesthetic experience. This simultaneity becomes especially salient at climactic moments such as the end of a piece, when collective applause engenders an emotionally charged atmosphere. By contrast, in the “Hypothetical Concert”, this simultaneity of attention unfolds at a deferred time and place. The audience, therefore, must imaginatively reconstruct the caravanserai in their minds to inhabit the performance.

In the absence of an audience, the re-performance of “Az Khoon-e Javanān-e Vatan” (From Our Youth’s Blood) with a new instrumental arrangement, invites novel listening experiences. Audience reactions across social media following the circulation of this performance corroborate this point. The song, composed by the poet and musician Aref Qazvini at the beginning of the Iranian Constitutional Revolution to commemorate its first martyrs, was published in the second Majlis of Iran in Tehran (Divan-e Aref 1978, 359). The piece was revived in the 1970s and performed by Mohammad-Reza Shajarian during the Revolution of 1979. It has since re-emerged as a protest song, including in Ahmadi’s performance during the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement. Its re-performance in the “Hypothetical Concert” intensified expressions of nationalist sentiment, pride, and the evocation of critical historical moments in modern Iran, such as the Constitutional Revolution, the 1979 Revolution, and the recent uprisings. In addition to the historical reason for the composition of the song “Az Khoon-e Javanan-e Vatan” (From Our Youth’s Blood), which was mentioned above, the symbolic structure and lexical texture of the piece have also endowed it with a protest function. Words such as blood, homeland, youth, and tulip signify the killing of young people across different historical periods in Iran. These sociopolitical transformations have enabled the revival of this song from the Constitutional Revolution to the Iran–Iraq War and, more recently, to the victims of contemporary Iranian protest movements. As a result, this piece becomes a sonic emblem of protest each time political violence leads to the death of the nation’s people.

The song “Mara Beboos” (Kiss Me) was another protest piece performed in the “Hypothetical Concert.” Originally released in 1957, coinciding with the execution of members of the Tudeh Party, the song came to symbolize both political struggle and love, for both the beloved and the homeland [2] (Malek 2014, 8). The song “Mara Beboos” (“Kiss Me”) was likewise transformed into a protest song due to the political and social circumstances in which it was written; otherwise, unlike “Az Khoon-e Javanan-e Vatan,” its lyrics are rooted in a romantic theme:

“Kiss me, for the last time,

May God protect you,

For I am going toward my fate.”

In this piece, the farewell seemingly imposed by political conditions creates a texture of dissent within the romantic premise. Beyond these specific examples, due to Parastoo Ahmadi’s public statement and the circumstances under which her concert was held, it is as though any song, regardless of its lyrical content, acquires a protestive character in this performance. Its inclusion in Ahmadi’s concert further intensified the political impact and emotional resonance of the performance for an audience.

THE ABSENCE OF PRESENCE IN RELATION TO THE HYPOTHETICAL CONCERT

The presence of an audience in a concert extends far beyond sitting in a hall and observing a performance. In the “Hypothetical Concert”, no spectators were present in the caravanserai. Yet this very absence created a horizon of receptivity and openness. Yet, as Heidegger argues, the decisive question lies in the search for the original unity of “unconcealment” and “concealment” (Heidegger 2012, 130). We are accustomed to setting presence and absence in opposition, or to valuing one above the other. Heidegger insists, however, that every unconcealment is possible only on the ground of concealment; without concealment, nothing could ever come to light. Absence, is not merely negative or defined by lack, but is itself an active force and a condition of presence (Hackett 2024, 31). Drawing on Heidegger’s thought, one may understand audience presence as a mode of “being-in-the-world” that goes beyond the mere acts of watching and listening to music. Presence entails a form of participation through which meaning emerges. This participation can generate for both audience and performer a sense of authentic and living experience, as though each approaches their genuine essence through music. In such a concert, presence appears as a possibility, while absence takes shape as a deferred possibility; both are bound together in an authentic unity. In his reflections on art, particularly in “The Origin of the Work of Art”, Heidegger regards art as a site in which the truth of Being sets itself to work. In contrast to the subjective stance that treats the subject as the source of meaning, logic, and mastery, the “Hypothetical Concert” directs us toward a realm of receptivity, openness, and absent presence. In this state, the audience stands at the threshold of meaning, suspended in a liminal zone between presence and absence, where the “I,” as audience, effaces itself so that what-is may come forth.

Figure 4: Parastoo Ahmadi and her Ensemble, December 2024.

When human beings are conceived as subjects and the world as object, the relation between the two is reduced to a subject, object dualism. Once we adopt the premise that “the human being is essentially a subject,” our mode of relation to the world, now construed as object,becomes aggressive, and the way to the truth of things is foreclosed (Abdolkarimi 2018, 280). In relation to the “Hypothetical Concert”, one can say that although the audience was not physically present at the moment of performance, Ahmadi performed under the presupposition of their presence. This “present absence” is a mode of presence that Heidegger situates within the concealment of truth. Heidegger then defines art as “the setting-into-work of the truth of Being.” Art, in its authentic sense, is not merely situated within history; it inaugurates history itself. It opens the historical horizon of a people and enables the unfolding and transmission of their collective historical self-understanding (Heidegger 2021, 57). Viewing this concert through a Heideggerian lens prevents us from interpreting the audience’s absence merely as a lack or void. Instead, it invites us to move beyond the binary of presence and absence, and to understand the audience’s suspended participation interrupted for political reasons as a form of authentic presence.

Musical performance (not necessarily in the form of a concert) is at times oriented toward the “other” (the audience). In a concert setting, an audience, through its presence and participation, confers identity upon the performers, enabling them to recognize themselves as a musician or singer. At times, the performer may even imagine an absent “other” as present during private practice; this very act of imagination presupposes the existence of an audience. Just as “Dasein” becomes aware of its Being in its encounter with nothingness, Parastoo Ahmadi, in the absence of her audience, imagines a form of presence, and it is precisely this absent audience that makes reflection on the rationale for the “Hypothetical Concert” possible.

Figure 5: Qamar al-Molouk Vaziri (1905-1959).

In the caravanserai, the virtual concert becomes a tangible experience of body, voice, and resistance against the historical prohibition of women’s singing in Iran, while the caravanserai itself becomes a site of meaning. In Iranian architecture, the caravanserai was a temporary lodging for travelers along their journey. Ahmadi’s performance in such a space becomes a moment of situated passage through the restrictions imposed on women’s musical performance, a path first opened a century ago by Qamar al-Molouk Vaziri, who appeared unveiled on stage at Tehran’s Grand Hotel and began her concert with a song based on Iraj Mirza’s famous anti-veil poem [3] (Siamdoost 2017, 31). For Qamar too, the choice of dress defying mandatory veiling laws carried legal repercussions. Ahmadi’s performance in a caravanserai without an audience thus symbolically reflects the condition of Iranian society across multiple historical junctures. The “Hypothetical Concert” and the responses it elicited, legal prosecution and censorship, were attempts to deny a reality that had already been actualized. The absence of an audience was nothing but the outcome of the historical compulsion of prohibiting women’s voices.

The prohibition of women’s singing and the imposition of compulsory veiling have produced a new texture for concert performance. The “Hypothetical Concert” has shifted the boundary between the live concert without an audience and the offline concert. The site of the performance, a caravanserai long abandoned, acquired new life through this event, reviving a space that may well have been forgotten in public memory.

In this performance, the audience became “present absentees” those denied the possibility of being in that world. Ahmadi, however, transforms this historical compulsion into an opportunity to rethink the very nature of the concert. In doing so, the “Hypothetical Concert” unsettles conventional boundaries between modes of performance and creates a living experience out of what would otherwise be classified as a failed attempt. If a concert is held and nobody hears it, does it make a sound?

NOTES

1. During the consent process for the interviews conducted in fall 2024, as well as prior to publication in fall 2025, I asked each interlocutor whether she preferred to have her real name used or to remain anonymous through a pseudonym. Two interlocutors chose to use their real names, while one preferred to be identified by her nickname. This choice is reflected in the manuscript.

2. The Tudeh Party of Iran is an Iranian Marxist-Leninist communist party.

3. “Her radiance melts the heart right through her mask / If she had none, God’s help we’d have to ask”

REFERENCES

Abdolkarimi, Bijan. 2018. Dar Jostjoye Moaseriat [In Search of Contemporaneity]. Naqde Farhang.

Hackett, William C. 2024. “Absent Presence, or Before the Principle of Contradiction: Blondel and Heidegger on στέρησις.” Duquesne Studies in Phenomenology 4 (1): n.p.

Heidegger, Martin. 2012. Bremen and Freiburg Lectures: Insight into That Which Is and Basic Principles of Thinking” Edited and translated by Andrew J. Mitchell. Indiana University Press.

Heidegger, Martin. 2021. The Origin of the Work of Art. Translated by Pirooz Zia Shihabi. 8th edition. Hermes.

Malek, Mohammad. 2014. In Taraneh Boye Nan Nemidahad: Sargozashte Tarane Motarez Dar Iran [This Song Does Not Smell of Bread: The History of Protest Song in Iran]. Bija.

Merriam-Webster. “Concert.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/concert

Nooshin, Laudan. “Our Angel of Salvation”: Toward an Understanding of Iranian Cyberspace as an Alternative Sphere of Musical Sociality." Ethnomusicology 62, no. 3 (2018): 341-374.

Qazvini, Aref. 1978. Divan of Aref Qazvini. Edited by Ahmad Seyed Azad. Amir Kabir.

Simadoust, Nahid. 2017. Soundtrack of the Revolution: The Politics of Music in Iran. Stanford University Press.

Small, Christopher. 1999. “Musicking — the Meanings of Performing and Listening. A Lecture.” Music Education Research 1 (1): 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461380990010102

Swarbrick, D., R. Martin, S. Høffding, N. Nielsen, and J. K. Vuoskoski. 2024. “Audience Musical Absorption: Exploring Attention and Affect in the Live Concert Setting.” Music & Science 7 (January 2024): https://doi.org/10.1177/20592043241263461