“If You Can Pay Rent, You’re Successful”: Transforming Success for Classical Singers

Samuel Harrison-Oram

Doctoral Researcher in Music

Royal Birmingham Conservatoire

Samuel.Harrison-Oram@mail.bcu.ac.ukIntroduction

UK conservatoire vocal departments often define success narrowly, prioritising solo performance careers within the classical music industry over other professional pathways (López-Íñiguez & Bennett 2020; Palmer & Baker 2021). In this context, conservatoire vocal students come to equate achievement with visibility, status, and prestige, measured through engagement with high-profile opera houses or vocal ensembles and/or competition success. Yet, for many graduates, the realities of working in a saturated and unpredictable freelance market following graduation prompt a profound reassessment of what success actually means for them as a working singer. For many professional singers, the pathway once assumed to define a successful career, characterised by linear progression through conservatoire training, participation in young artist programmes, and the pursuit of sustained performance engagements with opera companies or orchestras (Devlin & Martin 2016), no longer aligns with the realities of how most classically trained singers make a living today in the UK. This shift has prompted recent conservatoire vocal graduates to redefine success in terms of “portfolio careers” (Bennett & Bridgstock 2014), in which musicians engage with a diverse range of artistic practices such as performance, teaching, and community engagement.

To understand how these shifts in perception take shape, it is necessary to consider the wider social and economic conditions that frame the classical music profession in the UK. Research on cultural labour highlights how artistic work operates within capitalist and neoliberal systems that commodify creative practice, moralise artistic labour through discourses of passion and dedication, and reproduce existing social and institutional hierarchies (Qureshi 2003; Hesmondhalgh 2013; Wright 2010). These perspectives help to contextualise how singers’ definitions of success are formed not only through their conservatoire training but also through the wider structures of value that govern a shrinking and increasingly stratified performance economy.

This article draws on data from 35 UK conservatoire graduate singers and forms part of a wider mixed-method ethnographic study. It examines how singers renegotiate ideas of success developed during their conservatoire training within the contemporary UK classical music industry.

Institutional Narratives

Historically, UK conservatoire vocal and instrumental departments have promoted pathways designed to lead students toward classical performance careers as solo artists (Devaney, 2024; Gaunt et al., 2012). This emphasis on performance is reinforced at multiple levels: Palmer and Baker (2021) argue that conservatoires celebrate elite soloists in their marketing and narratives and model their assessment practices on the soloist career, positioning solo performance as the most successful outcome of training, and Carpio (2022) critiques the way conservatoire curricula remain firmly performance-centred, prioritising preparation for professional solo performance roles. Such patterns are echoed by many graduates in this study, as one conservatoire graduate stated: “I thought I had to sing opera to pay my way, plus oratorio solo engagements with teaching during the day… I thought I had to win competitions to succeed.” Palmer and Baker (2021) highlight how approaches to conservatoire pedagogies often privileges a soloistic performance-centric model, one that prioritises performance above other forms of professional practice. They find that such a focus can undervalue the training of wider skills that support a sustainable professional career. By framing success primarily through highly visible performance outcomes, teaching staff inadvertently perpetuate pressure on students to conform to restrictive definitions of achievement, leaving limited space for the development of wider competencies which are essential for long-term professional growth. Many graduates in this study recalled entering the industry with the belief that talent and hard work would inevitably secure consistent, high-profile opportunities, one graduate said that: “I thought if I sang well enough and worked hard enough, the jobs would come. That was the promise, unspoken but very much there,”[2] a reflection which represents a hidden set of attitudes that exist within conservatoire teaching practices, practices which are often embedded and hard to change. In the research literature on reform and change within the conservatoire model, students and institutional leaders have called for wider curricula that prepares young musicians for a wider range of careers, yet such proposals often meet resistance. Rumiantsev, Admiraal and van der Rijst (2020) link this resistance to the protection of traditional pedagogies, with concerns that broader provision may dilute technical rigour and established conservatoire values. Also highlighted by Duffy (2016), who notes that teachers who identify strongly with conservatoire traditions may also fear that reform could undermine their professional standing and thus impact their ability to earn a living. Such “old-guard”[3] attitudes then appear to lead resistance when innovations appear to challenge the conservatoire’s core emphasis on technical mastery through individual tuition.

Such dynamics sit within a wider cultural narrative in many conservatoires in which the threat of failure is reinforced and pursuing any career outside solo performance is often framed as a lack of success. Shaw (2023) found that many students began their conservatoire-level studies having already absorbed this perspective through earlier musical experiences, societal expectations, and a wider cultural emphasis on solo performance as the most legitimate career path for singers. Conservatoire environments consolidate these assumptions, which peers, families, and pre-conservatoire educational contexts initiate (Manturzewska 1990). However, students’ perspectives began to shift when they encountered more varied teaching models during conservatoire training, creating space for reflection and opening up new understandings of how their skills could be used professionally (Shaw, 2023). Such educational frameworks, which highlight transferable skills, pedagogical practice, and alternative career pathways, encourage students to reframe their skillset more broadly and to view professional success in less restricted terms. For the graduates in this study, the transition from training to professional work exposed significant gaps in conservatoire teaching and preparation, particularly in areas such as financial literacy, emotional resilience, and the skills needed to build and sustain professional networks, for instance, one graduates states that: “Once I was out in the world, I realised how little I had been taught about the actual demands of the job, networking, financial survival, what to do when your voice is not behaving.”[4] Such experiences highlight the urgent need for conservatory training to better reflect the realities of modern professional life, to challenge the assumption that a performance career is a solo performance career by default, and to equip students with the practical and emotional skills required to navigate an unpredictable, complex and fast-moving industry.

These accounts also foreground the tension between lived definitions of success and the dominant social values transmitted through conservatoire education. Harker (1984) contends that education systems sustain existing cultural hierarchies by promoting a limited and highly specific understanding of achievement, requiring individuals to assimilate with wider groups and attitudes in order to be recognised as successful within a given community. The classical singing profession in the UK positions a small group of professionals as legitimate examples of success, often these people are those teaching within conservatoire structures. In this context, it is perhaps unsurprising that conservatoires amplify and reproduce professional expectations and hierarchies. The impact of these dynamics is that conservatoires reinforce hierarchical expectations and limit students’ ability to imagine or pursue alternative pathways. Haddon (2012) identified related problems, observing that unspoken hierarchies and hidden curricula that continue to shape graduates’ trajectories long after formal study as they learned a number of “norms” while training. Connected to this, Shaw (2022) shows how relationships between “insider” and “outsider” groups, and between newcomers and established figures, shape practices and identities within conservatoires and beyond. Participants who provided data for this current study echoed such previous observations, describing how conservatoire teaching dynamics often reproduced the hierarchies they later encountered in the wider profession, as one graduate explained: “The environment often felt toxic, with no real transparency and a constant emphasis on protecting the reputation and importance of the institution rather than supporting the students themselves, and this was an attitude that I experienced later on when working.”[5] This reflection, typical of many across this study’s participant group, underscores the importance of transparency and student-centred practice within conservatoire education, revealing how institutional priorities can sometimes conflict with the developmental needs of emerging professionals.

Success Within a Capitalist Framework

Wider social and economic conditions that shape the music industry and constrain professional trajectories contextualise singers’ definitions of success. Such a reading draws upon a neo-Marxist critical framework: in this conceptualisation, a singer’s work is commodified by external market forces, its value is shaped not by intrinsic quality alone but by the ideology and hegemony of the classical music industry. This hegemony operates through the dominance of elite institutions, the industry’s relationship with the classical canon and entrenched pedagogical practices. Within this system, the singer becomes a vulnerable worker: their position depends on structures designed to benefit the designators of value. These include conservatoires, opera companies, agents, critics, and funding bodies, all of whom collectively define and control artistic worth. Qureshi (2003) acknowledges this logic as central to the classical music industry, arguing that its production is inseparable from capitalist systems that commodify artistic labour, while Hesmondhalgh (2013) highlights how cultural work is moralised through discourses of passion and vocation. Viewed through these lenses, singers’ experiences reveal how institutional narratives intersect with a shrinking and stratified UK performance market that ultimately positions the individual singer[6] as vulnerable within the industrial ecosystem.

Broader structures of capital, class, and social reproduction frame conservatoire cultures and professional identities. Wright (2010) argues that music education operates within capitalist and neoliberal systems that reproduce social hierarchies through hidden curricula and the privileging of middle-class cultural capital. Bates (2023) similarly notes that music education research often overlooks these structural inequalities, while Devaney’s (2024) study of socio-economic background in UK conservatoires shows how students from less privileged contexts frequently felt they were playing catch-up with peers who had benefitted from private tuition or financial support. In the majority of cases, participants in this and other studies shifted their aspirations in response to economic precarity during their training, with financial pressures restricting practice time and shaping career choices in ways that were structurally imposed rather than freely chosen.

DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS

This article draws on one strand of a wider mixed-methods project that collected data through three national online questionnaires administered to UK conservatoire vocal and operatic graduates, current conservatoire students and singing teachers. A total of 60 participants took part in the wider study, of whom 35 were graduates; it is this exploratory sample of graduate responses that forms the basis of the analysis presented here. While the broader project included multiple participant groups, the focus of this article is exclusively on graduates’ retrospective accounts of their conservatoire training and early professional experiences. The graduate questionnaire combined quantitative items, including Likert-scale[7] questions, open-ended prompts designed to elicit detailed contextualised accounts of participants’ educational and professional trajectories. Data was analysed using an iterative grounded theory approach,[8] in which themes were developed inductively through repeated cycles of coding, comparison and refinement. Constant comparison supported the identification of recurring patterns across participants’ accounts (Charmaz 2006). Participants’ language and interpretations were foregrounded throughout the analysis, and both the article and the wider study are situated within my ethnographic perspective as a professional singer and vocal coach.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Ethical approval was obtained for this study through the Faculty of Arts, Media and Design’s Ethics Committee at Birmingham City University. All questionnaire responses were gathered with informed consent: participants granted permission for the use of direct quotations in future publications, and anonymity was ensured by mutual agreement through a consent form integrated into the questionnaire design.

Findings

Transformation

Overall, the data indicates that participants’ understandings of what it means to succeed shifted markedly through reflection, time, and professional experience, with the transformation of attitudes emerging as the overarching theme. During their conservatoire training, many graduates understood success primarily as sustained visibility as a solo performer, most often within opera, and anticipated a linear pathway from undergraduate and postgraduate study into young artist programmes and regular freelance contracts. This expectation was reinforced by the sense of validation associated with conservatoire acceptance, which fostered the belief that talent and training would naturally lead to opportunity.

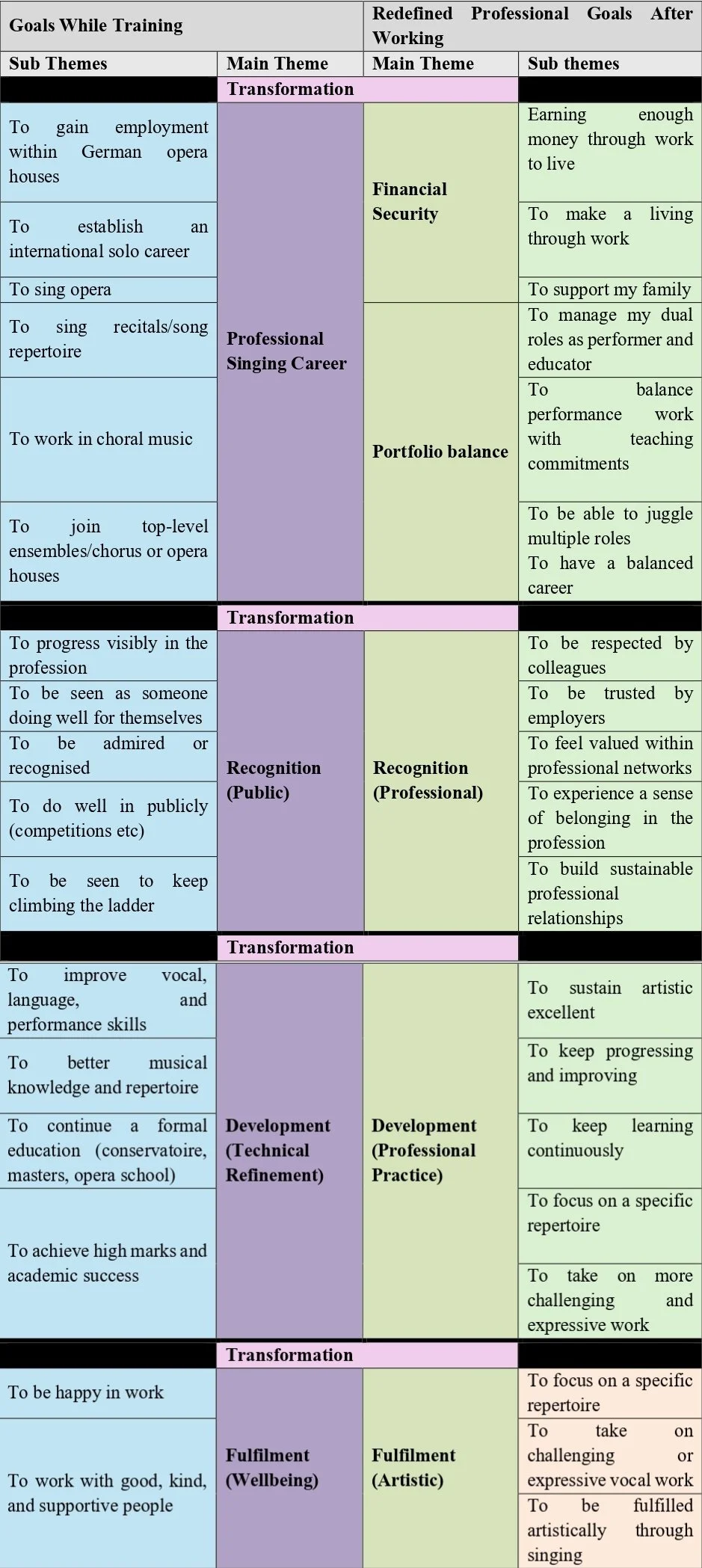

As graduates encountered the realities of freelance professional life, these assumptions were increasingly questioned and reworked. Table 1 illustrates how initial goals formed within conservatoire training evolved into broader professional priorities, with ‘transformation’ emerging as the central linking theme. This process reflects how singers reshaped, reframed and expanded their ambitions in response to lived professional experience, moving towards concerns of sustainability, balance and long-term viability. These emergent priorities often stood in tension with the soloist-centred norms and linear career narratives embedded within the conservatoire model, highlighting the need for professional development frameworks that extend beyond traditional measures of success.

Table 1: Transformation

During their training, graduates associated success with:

Performance-focused careers, particularly in opera and working as a soloist

External recognition through competitions and work with prestigious companies

Vocal technique refinement within an ongoing formalised learning

A sense of personal satisfaction through their work

After time in the profession, priorities shifted and transformed toward more sustainable measures of success, including:

Financial stability

Balanced portfolio careers that integrate performance, teaching, and other roles

Ongoing professional growth through continuous learning and development

The data reveals two other particularly interesting shifts:

Fulfillment became increasingly rooted in artistic values, with graduates placing greater emphasis on engaging deeply with specific repertoire and on the personal satisfaction derived from expressive and challenging vocal work, alongside rather than in place of earlier priorities relating to workplace happiness and supportive professional relationships. This shift also reflected a more professionalised orientation towards working relationships within the profession.

Recognition and external validation remained important extrinsic motivators for the graduates in this study, evolving from the way they sought approval from peers during training to seeking validation from their colleagues

Overall, the data shows that graduates consider adaptability and sustainability to be essential elements of a long-term professional portfolio career.

Professional Singing Career to Financial Security and Portfolio Balance

Upon entering the workforce, graduates say that they encountered a professional landscape characterised by uncertainty, demanding schedules, and structural inequities. Their initial vision of a singing career characterised by regular travel, sought-after solo engagements, or stable ensemble work often gave way to the more pressing need for financial security, leading to the development of a broader portfolio of activities that enabled them to stay afloat. For this group, financial instability quickly emerged as a dominant concern, reframing their definition of success around basic economic viability. As one graduate put it: “In reality, if you can pay rent, you are successful.”[9] Such a reframing is pragmatic, reflecting a deeper awareness of the pressures of freelance work and the need to align career ambitions with personal sustainability.

Graduates spoke of the intense physical and emotional demands of the profession: long hours, frequent travel, and the psychological strain of repeated rejection. “There was a period of 12 months where I had a total of six days off,” one graduate notes, continuing to say that “…work was fun, but the fatigue was impossible to manage, and I wish that I’d been taught how to manage myself under the strain–conservatoires did not support me in this preparation.”[10] For some, adaptive strategies developed gradually, helping them to navigate the uncertainties of a shifting profession. For others, the inability to adapt brought the danger of burnout, isolation, or even the decision to step away from a singing career altogether. As one participant reflected: “It felt like everyone else was figuring things out, moving forward, and I was just stuck. After a while, I couldn’t see where I fitted in anymore.”[11] These accounts reveal a clear divide between the narratives promoted by conservatoires during training and the realities perceived by students in early professional life, where confusion and uncertainty arose as they encountered limited institutional support following their transition into professional work and the absence of a support network became a normalised condition of the profession.

Recognition

Reflecting on their conservatory training, many graduates described success in terms of public and institutional recognition, such as high marks, competition success, visible progression, and approval from teachers or peers. These forms of validation confirmed status and belonging within the conservatoire environment. After entering professional work, however, such recognition proved uneven, unpredictable, and often beyond individual control. Limited opportunities, inconsistent audition outcomes, and opaque hiring practices led many graduates to reassess the value they placed on institutional approval. Recognition remained an important extrinsic motivator, but its meaning shifted. Graduates increasingly valued professional and relational forms of recognition, including respect from colleagues, trust from employers, and a sense of belonging within professional networks. As one participant explained, validation moved from “trying to impress teachers or win competitions”[12] to “feeling respected by the people I work with.”[13] This shift from public prestige to relational professional recognition signals a broader recalibration of how success is defined within a precarious and competitive profession.

Development - Technical Refinement to Professional Practice

Graduates state that conservatoire training largely focused on vocal technique delivered through individual singing lessons, and that continued study, whether at conservatoire, in opera schools, or through masterclasses, was expected to translate directly into career progression. Ongoing study was widely understood as an essential component of professional life; once working professionally, however, approaches to development began to shift. Development moved away from a primary focus on technical refinement towards a more integrated and self directed process, shaped by the demands of working life. Participants described continued attention to vocal health, repertoire development, technical adaptation across different performance contexts, and the practical management of freelance work. While artistic and technical growth remained central for some, the majority described these priorities as constrained by financial pressures, limited time, and the unpredictability of professional schedules. Professional development was therefore understood less as progression through fixed comparative milestones, such as technical proficiency measured against peers, and more as the ongoing maintenance of artistic practice within professional realities.

Fulfillment - Wellbeing to Artistic Satisfaction

Fulfillment became increasingly rooted in artistic values, with graduates placing greater emphasis on engaging deeply with specific repertoire and on the personal satisfaction derived from expressive and challenging vocal work, alongside rather than in place of earlier priorities relating to workplace happiness and supportive professional relationships. This shift reflected a more professionalised orientation towards working relationships and a broader reassessment of what constituted success after entering the workforce. As graduates encountered the realities of professional practice, success was increasingly measured through intrinsic values such as artistic growth, collaboration and wellbeing, rather than through external recognition or linear notions of “climbing the ladder.”[14] Over time, priorities shifted towards balancing multiple roles and seeking meaningful artistic engagement, signalling a maturing professional identity grounded in adaptability, balance and sustainable practice rather than public acclaim.

Portfolio Careers

For many, building it was the building of a portfolio career that created space for greater autonomy, enabling them to shape a professional identity that reflected their values and aspirations. For instance, one graduate stated that they benefited from “…a combination of income streams is super important. I do mostly choral work these days, and it pays better, is less stressful, fits in with my non-singing work, and there's more of it where I am. I supplement my singing income with other music-related work.”[15] What some had initially perceived as a sign of failure became, for many, a source of stability and artistic connection: “I used to think teaching meant you’d failed as a singer. Now I see it as part of my artistry. My students keep me connected to music in a way that auditions never did.”[16] The redefinition of teaching as an integral part of artistry mirrors the broader reality that many professional musicians sustain their careers through multiple roles, reflecting wider trends in the contemporary classical music profession, where portfolio careers are now the norm and musicians routinely combine performance with teaching, creative production, community engagement, and digital and entrepreneurial work (Bartleet et al. 2019). These reflections show how portfolio careers have become central to sustaining professional identity for many graduates, offering financial stability, creative independence, and a flexible framework for balancing artistic and personal fulfilment with the practicalities of modern working life. These patterns show that transformation is the core process through which graduates reinterpreted inherited conservatoire ideals, adjusted to the realities of freelance work, and constructed sustainable professional identities.

TRANSFORMING SUCCESS WITHIN A CONSERVATOIRE CONTEXT Transforming Success Within a Conservatoire Context

Such findings highlight the need to examine how conservatoire cultures shape students’ professional identities and careers within long-standing educational traditions that, as Porton (2020) observes, remain significantly under-researched. The graduates’ accounts in this study reveal a disconnect between their structured training and the complex realities of professional life. While institutional curricula tend to prioritise technical mastery and performance excellence, the professional landscape increasingly demands adaptability, entrepreneurship, and emotional resilience, areas for which graduates feel that they had been underprepared for during their training.

This disparity reflects a broader shift in the music profession toward what Westerlund & López-Íñiguez (2022) describe as a protean career, in which flexibility and personal agency are vital for navigating uncertainty and defining success. The graduates, meanwhile, described a process of self-formation as they reimagined what it means to succeed within an unpredictable and often precarious profession. Given these accounts, viewing students as protean artists might provide a more realistic framework for understanding their professional development within a modern conservatoire education. One participant reflected: “Now, success for me is being able to sing, to teach, and to live a life that doesn’t leave me constantly anxious. I don’t need Covent Garden to feel like I’ve made it.”[17] Such reflections reveal a shift not of diminished ambition but of resilience and agency. Many graduates sought careers that felt self-directed and sustainable, prioritising artistic fulfilment, collaboration, and well-being over external validation. Another participant explained: “At college, I thought winning competitions meant you’d made it. Now I know success is just being able to keep going and still love what you do.”[18] For these singers, portfolio careers offered both creative independence and stability, allowing them to integrate performance, teaching, and other related musical work. This evolution reflects a generational redefinition of what constitutes a sustainable career, one grounded in authenticity, adaptability, and well-being. As one graduate observed: “Happiness and fulfillment have nothing to do with having a glittery career. Success is working with the right people, meeting new colleagues, and creating special moments with music.”[19] Collectively, these findings reveal three interrelated themes: transformation, as graduates reassessed inherited ideals of prestige and visibility; adaptability, as they navigated the uncertainties of freelance work; and portfolio careers, as they constructed multifaceted professional identities that support both artistry and livelihood. Together, these patterns point to a profession in which sustainability depends less on institutional recognition and more on autonomy, self-knowledge, and the ability to shape one’s own definition of success.

Graduates entered a freelance market that demands adaptability and self-determination, rather than adherence to the linear, prestige-based model promoted during their studies, which many had assumed would lead naturally to career success. In redefining success, these singers moved towards values of balance, artistic fulfilment, and well-being, constructing portfolio careers that integrate performance, teaching, and collaboration. This redefinition represents not a loss of ambition but a reassertion of agency. Conservatoires must evolve their curricula to reflect realistic professional realities, cultivating not only artistic and technical excellence but also financial literacy, pedagogical confidence, and strategies for sustaining physical and mental health. By embedding these elements into core training, institutions can equip singers to define success on their own terms and thrive within the changing ecology of twenty-first-century musical life.

Notes

[1] Harrison-Oram, Samuel. 2024–2025. Professional Development in Vocal Pedagogy – Student Questionnaire. Unpublished questionnaire data, administered 22 August 2024 – 20 January 2025.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Although the term “singer” is used throughout this paper for consistency to describe graduates or those engaged in singing-related work, it risks masking the reality that these individuals’ personal and professional lives are deeply intertwined with the precarious structures of the industry. The classical music sector often exploits their dedication, demanding total commitment while providing little stability. As a result, those who uphold its culture are rendered effectively disposable within its economic and institutional hierarchies. In this context, their humanity is subordinated to the demands of production, as individuals are frequently treated as interchangeable within an oversupplied and intensely competitive labour market.

[7] A Likert scale presents respondents with a series of statements and asks them to indicate how much they agree or disagree–typically from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree”. It was useful in this study because it allowed us to quantify singers’ attitudes and compare patterns across our sample. (Joshi et al. 2015)

[8] In grounded theory, coding refers to the analytic process of breaking qualitative data into smaller units of meaning, assigning labels to these units, and comparing them across the dataset. Through successive stages of coding, recurring motifs and patterns can be identified and refined into more focused categories, which support the development of emerging themes.

[8] Harrison-Oram, Professional Development in Vocal Pedagogy Questionnaires (unpublished questionnaire data).

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

References

Bartleet, Brydie-Leigh, Christina Ballico, Dawn Bennett, Ruth Bridgstock, Paul Draper, Vanessa Tomlinson, and Scott Harrison. 2019. “Building Sustainable Portfolio Careers in Music: Insights and Implications for Higher Education.” Music Education Research 21 (3): 282–94.

Bates, Vincent C. 2023. “Capital, Class, Status, and Social Reproduction in Music Education: A Critical Review.” Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 22 (1): 46–78.

Bennett, Dawn, and Ruth Bridgstock. 2014. “The Urgent Need for Career Preview: Student Expectations and Graduate Realities in Music and Dance.” International Journal of Music Education 33 (3): 263–77.

Carpio, Rebekah. 2022. “Expanding the Core of Conservatoire Training: Exploring the Transformative Potential of Community Engagement Activities within Conservatoire Training.” PhD diss., Guildhall School of Music & Drama, University of London.

Charmaz, Kathy. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. Sage.

Devlin, Graham, and Fanny Martin. 2016. Opera Training for Singers in the UK: A Review of the Sector. Graham Devlin Associates.

Devaney, Kirsty. 2024. “How Much Are You Willing to Give Up? Investigating How Socio-Economic Background Influences Undergraduate Music Students’ Experiences and Career Aspirations within UK Conservatoires.” Research Report. Royal College of Music. https://researchonline.rcm.ac.uk/id/eprint/2560/.

Duffy, Celia. 2016. “ICON: Radical Professional Development in the Conservatoire.” Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 15 (3-4): 376–85.

Gaunt, Helena, Andrea Creech, Marion Long, and Susan Hallam. 2012. “Supporting Conservatoire Students towards Professional Integration: One-to-One Tuition and the Potential of Mentoring.” Music Education Research 14 (1): 25–43.

Haddon, Hilary Elizabeth. 2012. “Hidden Learning and Instrumental and Vocal Development in a University Music Department.” PhD diss., University of York.

Harker, Richard K. 1984. “On Reproduction, Habitus and Education.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 5 (2): 117–27.

Hesmondhalgh, David. 2013. The Cultural Industries. Sage.

Joshi, Ankur, Saket Kale, Satish Chandel, and D.K. Pal. 2015. “Likert Scale: Explored and Explained.” British Journal of Applied Science & Technology 7 (4): 396–403.

López-Íñiguez, Guadalupe, and Dawn Bennett. 2020. “A Lifespan Perspective on Multi-Professional Musicians: Does Music Education Prepare Classical Musicians for Their Careers?” Music Education Research 22 (1): 1–14.

Manturzewska, Maria. 1990. “A Biographical Study of the Life-Span Development of Professional Musicians.” Research in Psychology of Music and Music Education 18: 112–39.

Palmer, Tim, and David Baker. 2021. “Classical Soloists’ Life Histories and the Music Conservatoire.” International Journal of Music Education 39 (2): 167–86.

Porton, Jennie Joy. 2020. “Contemporary British Conservatoires and Their Practices – Experiences from Alumni Perspectives.” PhD diss., Royal Holloway, University of London.

Qureshi, Regula Burckhardt. 2003. Music and Marx: Ideas, Practice, Politics. Routledge.

Rumiantsev, Tamara W, Wilfried F Admiraal, and Roeland M van der Rijst. “Conservatoire Leaders’ Observations and Perceptions on Curriculum Reform.” British Journal of Music Education 37, no. 1 (2020): 29–41.

Shaw, Luan. 2023. ‘‘If You’re a Teacher, You’re a Failed Musician’: Exploring Hegemony in a UK Conservatoire.” Research in Teacher Education 13 (1): 21–27.

Shaw, Luan. 2022. “Facilitating the Transition from Student to Professional through Instrumental Teacher Education: A Case Study with Main Reference to the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire.” PhD thesis, Birmingham City University

Westerlund, Heidi, and Guadalupe López-Íñiguez. 2022. “Professional Education toward Protean Careers in Music? Bigenerational Finnish Composers’ Pathways and Livelihoods in Changing Ecosystems.” Research Studies in Music Education 46 (1): 66-79.