Listening through the Frame: Videography and Gendered Narratives in Tan Dun’s Nu Shu (2013)

Xuan He

Ohio UniversityPhoto from a performance of Tan Dun’s Nu Shu. Photo by Xuan He.

When I first stumbled upon Tan Dun’s Facebook post featuring Water Rock’n’Roll, a segment from his Nu Shu:The Secret Songs of Women – Symphony for Harp, 13 Microfilms, and Orchestra (2013), I was unexpectedly moved.[1] The video begins with a close-up of hands rhythmically striking water. As the frame widens, it reveals several women from Jiangyong County, a rural area in Hunan, China, known as the birthplace of nüshu, the world’s only known female-specific writing system (Liu 2017, 231). The women gather by the river in their traditional indigo-blue garments, washing clothes in a steady rhythm as their singing unfolds in tandem. The sounds of slapping water and shifting fabric converge with their voices, transforming this moment of domestic labor into a vivid and embodied sonic encounter.

What first appeared to me as a spontaneous ethnographic moment soon unraveled into something more complex. In the video’s caption, Tan writes, “I invited five young musicians to the village to live with the female practitioners of Nu Shu. They played the pond as a big drum, following the beat to do their laundry” (Tan 2016).[2] I then realized that the powerful water percussion had been performed not by local women, but by trained musicians. Further research revealed that the melody in the video was adapted from Jintuo Nü [“Golden Lump Girls”], a well-known song from the nüshu tradition. However, the lyrics were written by Tan himself and diverged from the original text. That moment marked a turning point in my engagement with Nu Shu, Tan Dun’s multimedia symphony rooted in the nüshu tradition.[3] What moved me was the natural vitality that emerged from women’s labor and song. It was a force that felt unfiltered, communal, and alive. Yet as I learned more, I began to question what I was seeing and hearing. Where does documentation end and stylization begin? How do field recordings, performers, and compositional agency converge? My response shifted from wonder to critical reflection.

Tan Dun, a Chinese American composer renowned for blending Eastern and Western musical vocabularies, rose to international prominence with his Oscar-winning score for Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000). Spanning film, opera, and experimental concert music, his compositions often center on ritual, cultural memory, and sonic practices that fall outside dominant musical narratives (Bard College Conservatory 2024). Among these, it was nüshu—a women’s script rooted in rural Hunan’s oral and emotional lives—that resonated most deeply with Tan. Nüshu is a phonetic script that women developed in response to their exclusion from formal education. It took shape in Jiangyong through the interplay of linguistic, social, and ritual conditions: the phonological regularity of the dialect, sworn sisterhood and community-based female networks, and emotional practices tied to oral exchange (Liu 2004, 433–437; Liu 2012, 206–210; Liu 2017, 235).[4] Nüshu texts are typically handwritten on paper, fans, or cloth, and exchanged during life-cycle events such as weddings and mourning. Though concise in form, their language is rhythmic and emotionally direct. Its narratives often dwell on the hardships of unhappy marriages and intimate emotional suffering, prompting many users to burn or bury their texts before death (Liu 2004, 433–437; Liu 2017, 235). Crucially, nüshu is not intended for silent reading; it is performed aloud, transforming personal memory into embodied and shared sonic expression.

Tan’s engagement with nüshu was not merely aesthetic; it was shaped by cultural memory and personal resonance. He was born in Hunan, the same province as Jiangyong, and linked the region to his rural childhood and to memories of his mother’s voice. In several interviews, Tan reflects on the emotional depth he observed among nüshu singers, particularly in the recurring presence of tears, which he describes as a powerful marker of feminine culture (Tan 2013; BBC Chinese 2016).[5] These impressions informed his desire to honor women’s inner worlds, and he conceived Nu Shu not as documentation but as a tribute. Between 2008 and 2013, Tan conducted five years of fieldwork in Jiangyong County, recording over 200 hours of footage and vocal performances. The final work consists of thirteen “microfilms,” accompanied by harp solo and symphony orchestra, forming a dual narrative of sound and image that traces the arc of women’s lives in Jiangyong.[6]

Yet Tan’s role as videographer, director, and composer gives him substantial control over how these women are seen and heard. His authority raises questions about the gaze, particularly its male, intellectual, and global dimensions, since Nu Shu is created for an international audience. As Titon (2008, 25) suggests in Shadows in the Field, the field is not a neutral space of observation but a negotiated site of roles, visibility, and power. These conditions align with the broader concept of the gaze, in which the act of seeing is inseparable from structures of authorship and representation. In this context, Tan occupies a dual position. He is both an insider, as a native of Hunan with deep knowledge of local traditions, and an outsider, as a globally celebrated male artist engaging with a female-centered cultural form. This hybrid positionality complicates his authorship. On the one hand, it may deepen his empathetic vision; on the other, it risks contributing to the aestheticization, romanticization, or even objectification of the women represented in his work.

A central feature of Nu Shu is Tan’s use of organic media such as water, stone, and voice. These materials function as both sonic elements and cultural symbols that attempt to translate feminine memory into a multisensory experience of ritual and intimacy. Despite their immediacy, they remain mediated through visual and symbolic frames shaped by authorship. This contradiction raises a guiding question: does Nu Shu amplify Jiangyong women’s voices, or does it reframe them within a stylized representational structure?

To explore this tension, I adopt a critical feminist framework to examine how Nu Shu navigates power, gender, and authorship. Drawing on Nancy Yunhwa Rao’s (2023) theory of sonic materiality and Christopher Small’s (1998) concept of “musicking,” I analyze how Tan’s compositional choices stage and translate female sonic expression within a gendered audiovisual regime.

This analysis unfolds in three sections. The first traces the patriarchal logic embedded in nüshu and bridal laments. It shows how female sorrow has been ritualized, repressed, and rebranded through heritage discourse. The second examines how Tan reimagines this tradition through music and videography. It reveals the aesthetic and ethical tensions in his translation. The third offers close readings of selected microfilms. It demonstrates how audiovisual strategies construct emotional resonance while also shaping, and at times constraining, female subjectivity. Together, these sections argue that Nu Shu both channels and reconfigures female voices through a deeply mediated sonic and visual structure.

Celebrating the Right to Grieve? Kuge [Bridal Lament] and the Gendered Politics of Voice in Nüshu Tradition

“今天是娘家的贵女,明天成了婆家的贱人。”

I am a precious daughter in the eyes of my family,

Yet I will be reduced to nobody at the in-laws’ house from now on.

—— Wailing Songs at Weddings (Xiang and Xiang 2021, 45)

Scholars generally agree that nüshu likely emerged during the mid- to late-nineteenth century, although local legends trace its origin as far back as the Song dynasty (960–1279) (Liu 2004, 433–434). As previously noted, nüshu was not merely a written code, but a gendered practice embedded in oral and performative traditions. Its performative dimension ties closely to nüge [women’s folk songs], particularly kuge [bridal laments], which were composed and sung as ritualized expressions of female emotion during wedding ceremonies (Liu 2012, 207–210).[7] In the days leading up to the wedding, the bride would participate in a ritual called zuogetang [sitting song hall], held in a designated room of her natal home. The core of this ritual was the performance of kuge, in which the bride, surrounded by her female relatives and local women, sang farewell songs marked by emotional fragility and heartfelt sorrow. This anguish is captured in a widely cited lyric presented above. Despite the emotional weight of parting, the bride’s sorrow had to conform to a tightly structured ceremonial script. As anthropologist Fei-Wen Liu (2012) observes, these laments were not raw outpourings of feeling but stylized performances shaped by communal norms. A bride who failed to cry convincingly might be seen as lacking proper upbringing, whereas a moving lament affirmed her filial piety and moral virtue (204–225).

On the other hand, a close reading of kuge lyrics reveals that beneath the ritual surface, women engaged in a range of discursive strategies that allowed them to voice discontent, negotiate power, and reshape meaning. Brides may curse the matchmaker who arranged the marriage, express envy toward male privilege, or voice anxieties about their future in a husband’s home. Some verses are surprisingly pragmatic, conveying satisfaction with the dowry or advocating for fair treatment (Xiang and Xiang 2021). As Chinese studies scholar Anne McLaren notes, “the individual performer is involved in neither resistance nor compliance but in a process of debate and negotiation of contested cultural values” (2008, 8). These discursive gestures within kuge suggest that emotional expression in bridal laments was not a binary of submission or resistance, but a nuanced negotiation of womanhood under constraint.

The tension between articulating female grievance and conforming to patriarchal codes calls to mind Luce Irigaray’s (1985) critique of how femininity is shaped within male-centered cultural frameworks. In This Sex Which Is Not One, Irigaray argues that patriarchy constructs femininity through cultural norms that flatten the richness and plurality of women’s lived experiences into symbolic ideals defined by male desire ([1977] 1985, 30–31, 86). She suggests that such symbolic economies do not simply silence women but structure how female subjectivity can appear. In the case of kuge, even stylized expressions of sorrow are shaped by communal expectations that frame what kinds of female pain are legible, respectable, or virtuous. Still, the very act of voicing these laments, though highly coded, carves out a space where women can, however subtly, reframe normative identities. Judith Butler extends this critique in Undoing Gender by introducing the concept of the “right to grieve,” arguing that public mourning is a privilege granted by dominant cultural frameworks rather than a neutral human entitlement (2004, 22–25).[8] Within the ritualized structure of kuge, we can see this logic at work. The bride’s sorrow must conform to communal scripts that define acceptable forms of female emotion. What appears as personal pain is, in effect, a performance of culturally sanctioned grief that upholds social expectations of feminine behavior instead of challenging them. In this sense, kuge is less a space of unfiltered self-expression than a gendered obligation which recirculates the values it might seem to resist. This logic finds particular relevance within the social conditions of pre-modern rural China, where arranged marriage and gendered emotional codes shaped how women’s grief was both expressed and constrained.

The patriarchal shaping of kuge was deeply rooted in cultural tradition and further reinforced through political institutionalization. After 1949, the Chinese government condemned the nüshu tradition and its vocal practices, including kuge, as “relics of feudalism” and targeted them in campaigns against superstition. During the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), both their performance and scholarly research were explicitly banned as backward forms of womanhood incompatible with socialist ideals and revolutionary values (Liu 2012, 215–216; Liu 2017, 241–242; McLaren 2008, 35–36). Under post-socialist cultural governance, however, nüshu has been recontextualized from a marginalized vernacular practice into a stylized emblem of national heritage, repackaged as a picturesque marker of ethnic tradition. Yet in the process, its critical dimensions have often been muted. Among these are its capacity to express gendered sorrow, to question heterosexual marital norms, and to articulate emotional dissent within patriarchal structures. (Liu 2012, 215–216; Liu 2017, 240–244). Rather than foregrounding these tensions, heritage discourse tends to present nüshu in the language of harmony, continuity, and picturesque tradition.[9] As a result, the performative edge of kuge is softened, their emotional intensity stylized, and their historical role reframed as a quaint display of ethnic culture. No longer unsettling dominant narratives, these practices are positioned to reflect a cohesive cultural image aligned with nationally endorsed heritage values.

Reflecting on these observations, I find that kuge demands to be approached with critical attention to its embedded contradictions, such as the tension between emotional expression and ritual regulation, or between female agency and patriarchal containment. Kuge embodies a fraught interplay among personal grief, ritual performance, critique, and conformity to patriarchal order, offering perhaps an early and culturally specific articulation of feminist consciousness in East Asian contexts. While they offer space for female voices, kuge challenges any straightforward reading as a form of proto-feminist rebellion. Their expressive potential is always shaped, sometimes enabled and sometimes constrained, by the very structures they seem to resist. For this reason, artists and composers who engage with lament traditions must navigate this delicate terrain with care, resisting both romanticized feminism and nationalist spectacle. In what follows, I turn to Nu Shu to examine how Tan contends with this legacy and reimagines it through contemporary musical practice.

From Tears to Timbre: Materiality and the Gendered Voice in Tan Dun’s Nu Shu

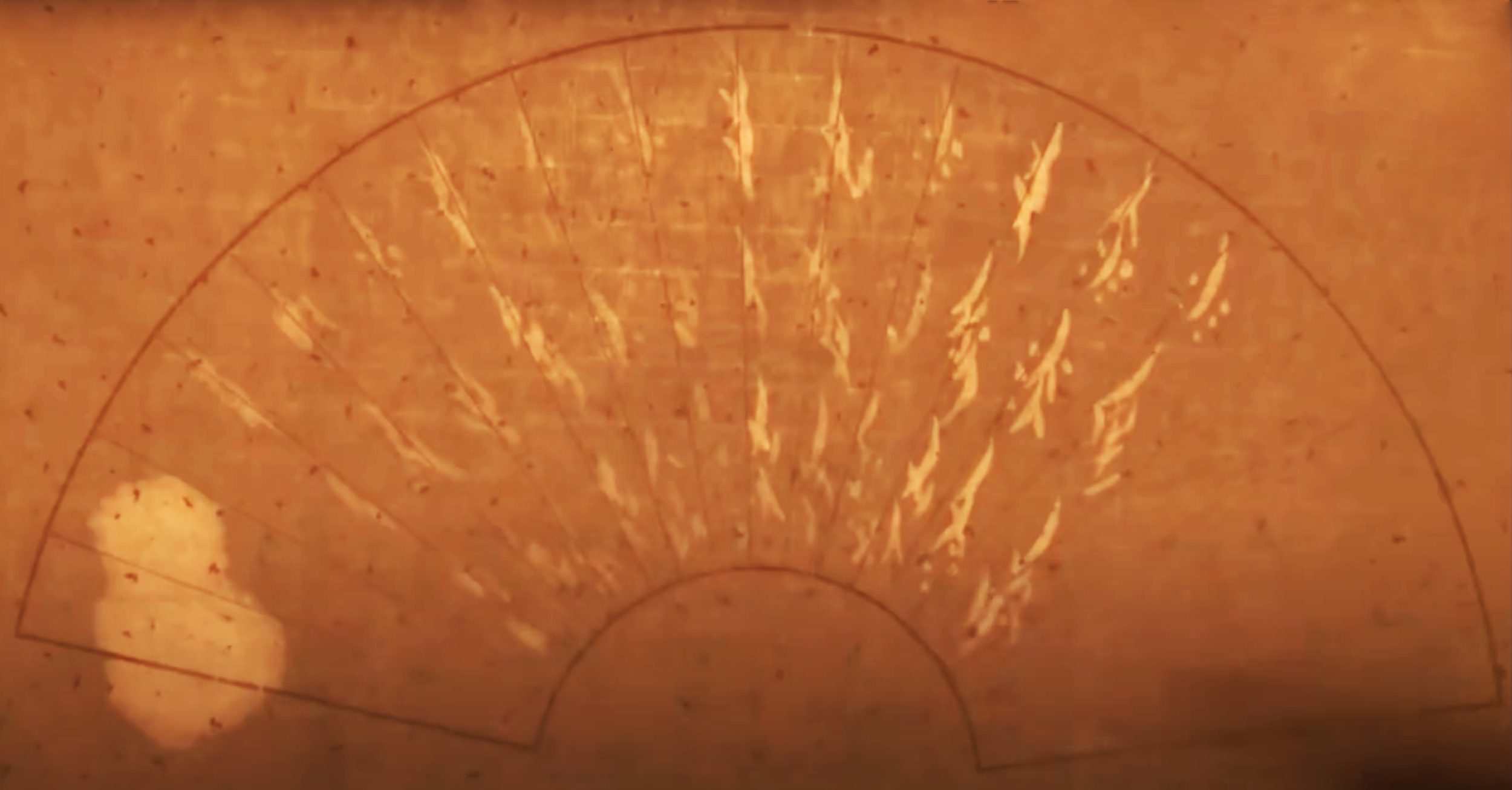

Figure 1. Writing the nüshu characters for “mother,” “daughter,” and “sworn sister” on a paper fan using water as ink. Captured in the first microfilm of Nu Shu, this moment sets both the narrative and symbolic foundation for the work.

The opening microfilm of Nu Shu depicts a brush dipped in water writing three nüshu phrases— “mother,” “daughter,” and “sworn sister”—on the surface of a fan (Figure 1). This gesture introduces the work’s narrative structure: its thirteen movements are organized around these three pivotal relationships in a woman's life in the nüshu tradition.[10]

Meanwhile, the use of water as ink evokes a symbolic system that recurs throughout the work. Water references the flowing contours of nüshu script, the tears passed down through generations of women in Jiangyong, and the aqueous geography of Jiangyong’s rivers and ponds. The harp, featured as the solo instrument, extends this watery metaphor through its fluid, cascading timbre, and its role in musically linking otherwise discrete movements. Beyond its sonic symbolism, the harp also carries significant gendered and cultural associations in both Tan’s framing and broader instrumental tradition. Although Tan Dun’s pairing of the harp with feminine symbolism seems intuitive, it is far from unexamined. In a 2013 interview, Tan noted:

The harp is a highly feminized instrument—most orchestration manuals describe it as decorative. That made me think of nüshu. In a man’s world, women were also seen as decorative. My rebellion was to make the harp melodic, full of drama and tension. I told the soloist, “You must play with charisma, as if you’re a historical giant telling the story of women’s culture.” (Qian 2015).

This gendered symbolism aligns with broader associations of the harp in Western orchestral tradition as a feminized, ornamental, and often domesticated instrument. A notable case is the harp’s symbolic role in 19th-century Ireland, where its visual and cultural representation often aligned it with feminine qualities and national sentiment, making it a vehicle for political affect in the domestic sphere (Dyall 2023).

This becomes even more complex when we consider that, as Henry Spiller (2019) argues, the harp’s cultural coding extends beyond simple feminization. Drawing from a queer organological perspective, Spiller uncovers how the pedal harp has historically been associated with aesthetic marginality, decorative timbre, and spatial removal within the orchestra—qualities that embed it with a deeper cultural unconscious of gendered and sexual otherness. Unintentionally, Tan’s framing of the harp activates these resonances. Its physical posture, ornamental associations, and affective ambiguity align uncannily with Nu Shu’s central themes of gendered marginalization and cultural concealment. His reinterpretation thus reclaims this coded marginality as an expressive force. However, this reclamation does not arise from a fully conscious engagement with the harp’s queer potential; rather, it reflects an intuitive symbolism that risks reinscribing the very gendered logic it seeks to resist. The expressive power of the harp in Nu Shu thus rests on a symbolic structure that remains only partially interrogated.

Building on this symbolic reconfiguration, the harp’s role in Nu Shu also reflects Tan’s broader compositional philosophy, particularly his notion of “organic music,” in which water operates both as an acoustic element and as a symbolic thread woven through his compositional thinking.[11] Since the late 1990s, Tan has incorporated materials such as stone, paper, and ceramic alongside water. These are not merely sound sources, but expressive agents charged with cultural and symbolic resonance. Works including Water Concerto (1998), Water Passion after St. Matthew (2000), Paper Concerto (2003), and Earth Concerto (2009) show his commitment to what he calls an “organic” approach to music-making. Inspired in part by his rural upbringing in Hunan and influenced by the experimental legacy of John Cage, Tan sought to transform everyday objects into carriers of sonic and spiritual resonance. He has noted that such music conveys a connection between nature and the inner spirit (Tan 2011). This “organic” approach involves more than the use of natural materials; it also engages with contradiction through musical and visual layering. It uses breath, gesture, and fragmented narrative to reflect rather than resolve tensions between visibility and erasure, between ritual authenticity and aesthetic stylization.

Tan’s engagement with natural materials has drawn sustained scholarly interest. Among these contributions, music theorist Nancy Yunhwa Rao (2023) offers a conceptually grounded approach through her theorization of “sonic materiality” in contemporary Chinese and intercultural music. Rao expands the notion of materiality beyond the physical properties of sound-making media to include their symbolic and embodied dimensions, providing an alternative framework for analyzing non-Western music. In the same essay, she takes Tan Dun’s Tea: A Mirror of Soul (2002) as a case study, showing how materials such as paper, water, and clay operate as agents of cultural memory and embodied gestures within the compositional process (Rao 2023).[12]

This framework is especially useful for understanding Nu Shu, where the singing voice does not emerge from a live performing body but from the audiovisual space of Tan’s “microfilms.” In order to examine how Nu Shu gives form to gendered vocal subjectivity, it is necessary to attend to what is heard, as well as how the voice is staged, situated, and shaped by its visual environment. As I argue in the following analysis, it is through this interplay of sound and image that Nu Shu renders audible and visible the affective agency of the women whose laments it seeks to preserve. At the same time, this agency is mediated and, at times, constrained by visual framing and orchestral stylization. This is not to suggest that kuge was a site of unmediated expression. As discussed in the previous section, its performative space was already conditioned by patriarchal expectations. What Nu Shu introduces is an additional layer of mediation, realized through aesthetic, technological, and compositional strategies that both preserve and transform the gendered logic of sorrow.

Despite being titled A Symphony for Microfilms, Harp Solo, and Orchestra, Nu Shu resists fixed hierarchies or stable counterpoint among its three components. As noted earlier, the nüshu singing style reflects what Liu (2004) describes as “read-singing”—a fluid blend of recitation and chant. Therefore, these songs often use narrow ranges, three- or four-note scales, and pentatonic phrases centered on the degrees jue and yu, typically resolving to yu, a defining feature of the yu mode.[13] Such melodic economy limits the number of available phonemes in texted movements and calls for harmonic and timbral elaboration from the harp and orchestra. Meanwhile, in free-rhythm laments where pitch and timing fluctuate unpredictably, the orchestra cannot easily “accompany” in a traditional sense. Instead, it provides a sparse, atmospheric backdrop, characterized by repetition and openness, supporting the expressive intensity of the voice without overpowering it. In addition to movements that feature nüshu singing, three of the thirteen are purely instrumental, relying on the interplay between the harp and orchestra to sustain continuity and mood. Based on the foregoing discussion of audiovisual interaction, Tan composed a stylistically similar nüshu melody to resonate and integrate with the chanting featured in the microfilms. Drawing on the characteristic intervals of nüshu vocal intonation, this theme recurs in the first, third, fifth, and thirteenth movements, providing emotional continuity and structural cohesion (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Nu Shu theme’s first appearance, in the harp solo at measure 10.

In what follows, I draw on Rao’s theories of materiality and subjectivity to examine the fourth movement of Nu Shu, Cry-Singing for Marriage (interchangeable with kuge). In this scenario, the bride, about to depart for her marriage, and her mother each hold a long piece of cloth, cry- singing together in profile view without showing their full faces (Figure 3). The movement opens with the harp arpeggiating a Cmaj7♯5(9) chord (C–E–G♯–D), a rich yet ambiguous sonority. While built on a major chord, the sharp fifth and added tensions blur its tonal center, setting a mood that is fluid, refractive, and unresolved. This sonority recurs throughout the movement, serving as both a musical anchor and a symbolic thread that evokes emotional tension and flowing memory (Figure 4). Two upward brass glissandi (sliding pitch effects) heighten a sense of instability and suspension before the voice enters. As the microfilm begins, the bride’s mother comes into view, and the cry-singing unfolds in tandem with her appearance.

Figure 3. Opening harp gesture in Nu Shu, movement IV. The arpeggiated chord (C–E–G♯–D) sets the movement’s harmonic tone and recurs as a structural motif.

Figure 4. Still image of cry-singing between the bride and her mother, in a call-and-response format.

This movement stages an antiphonal exchange between a mother and daughter, rather than a polyphonic duet. Their voices span an octave—mother in the lower register, daughter in the higher—but remain confined to the range of a fifth. While musically simple, the staging is highly expressive: the two women face each other, each holding one end of a long cloth. As they alternate in singing, their breath-driven voices travel visually across the cloth, which rises and falls with each phrase. The cloth becomes a tactile and visible extension of the vocal line, emphasizing the directional force of the sound and the embodied connection between the singers.

Surrounding them in a semicircle, other women speak quiet words of consolation in an everyday tone. These voices create a low-frequency sonic field beneath the more penetrating vocal lines of the cry-singers. Notably, the harp’s continuous arpeggiation evokes a flowing, watery texture that unifies the singers, the spoken voices, and the orchestral backdrop into a shared soundscape. The simultaneous cessation of cry-singing, harp, and orchestra marks a moment of sonic resolution, underscoring the expressive climax of the movement.

Although the scene is framed in ritualistic terms through its costume, setting, and thematic content, there are discernible traces of spontaneity and interpretive freedom embedded within the performance. Tan omits the singers’ lyrics from the score, and orchestral entrances are cued by video timecodes rather than conventional measure numbers. These compositional choices suggest a deliberate restraint: instead of fully staging the lament as a fixed folkloric form, Tan leaves space for situated vocal spontaneity. His sensitivity to spatial positioning and the directional force of sound, especially the embodied gestures linking the two singers, reveals a commitment to treating vocal material not as passive quotation but as agentive presence. This movement exemplifies what Rao describes as the “presence” of sound—its entanglement with gesture, breath, and collective affect. When cry-singing is mediated through audiovisual form, it becomes not merely an acoustic expression but an instance of embodied vocal subjectivity. In addition, like kuge, which carved expressive space within patriarchal rituals, Tan’s approach opens a space for contingent vocal agency. In academic music traditions, composers are typically treated as the primary authors of meaning, while performers are positioned as interpreters. By resisting this hierarchy and emphasizing breath-driven spontaneity, Tan invites us to hear music not as a self-contained work but as a relational act shaped by all who take part. This approach aligns closely with Christopher Small’s concept of musicking.

Seeing Sound, Hearing Image: Musicking Across Audiovisual Frames

In the previous section, I explored how Nu Shu constructs the vocal subjectivity of nüshu female singers through audiovisual means. I now turn to the viewer’s role in this construction, focusing in particular on how gendered modes of perception shape the reception of female voices. Music sociologist Christopher Small challenges the Western tradition of treating music as a fixed object, emphasizing instead its ritualistic and social dimensions. He understands music as a dynamic process of interaction among composers, performers, and listeners (1998, 26–27). Moreover, Small argues that perception is never neutral; it is filtered through past experiences, including deeply internalized notions of gender. As he writes, “the effect of the differences, what we actually experience as perception, is a transform, or coded vision, of the physical differences that engendered it” (1998, 54). Greater divergence in personal histories corresponds to more varied responses to the same sensory stimuli, particularly across lines of race, class, gender, and cultural background. This has profound implications for performance: bodily gestures in music are not innate or universal, but socially constructed expressions shaped by one’s identity and positionality. In the case of Nu Shu, this includes the cultural expectations placed upon female bodies and voices. Recognizing that our interpretations of both music and image are deeply conditioned by lived experience, including gendered ways of seeing and hearing, invites us to engage more consciously in musicking—as a dynamic process of being seen and seeing, of conforming and resisting within gendered and shifting frameworks of meaning.

In Nu Shu, this participatory perspective prompts me to reconsider how sound is perceived and draws attention to how visual strategies frame our encounter with nüshu singers’ voices. The viewer engages not passively but actively, shaped by the emotional cues of camera positioning, framing, and rhythmic editing. To better understand how visual design shapes the reception of nüshu voices, I now return to the third movement, Dressing for the Wedding, which contrasts sharply in both tone and visual strategy with the fourth movement discussed earlier.

The third movement, Dressing for the Wedding, reconstructs a traditional coming-of-age ritual historically practiced by girls in Jiangyong at the age of fifteen, just before marriage. Contrary to the fourth movement, in which the camera alternates between two featured singers, this movement pushes the central figure, the bride-to-be, to the margins of the visual field. Her presence appears fragmented, often mirrored at the edges of the screen, while the center remains occupied by older women who sing as they braid her hair and prepare her for departure (Figure 5). This subtle visual distortion stands in stark contrast to the musical texture, which is the most forceful in the entire work: a tutti (full ensemble) involving both voice and the full orchestra, grounded by a relentless percussive pulse played on stones. The timbre evokes the sound of a battle drum, suggesting not celebration but confrontation. Only at the end, when the girl is fully adorned with a massive traditional silver crown, her face finally appears at the center of the screen. Yet even then, her eyes are obscured by the heavy tassels cascading from the headdress (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Still image from Dressing for the Wedding (1)

Figure 6. Still image from Dressing for the Wedding (2)

To me, this is the most overtly ritualistic movement in Nu Shu, both formally and symbolically. Through the fragmented visual framing and the visceral sonic intensity, Tan suggests that the girl is not entering a ceremonial rite of passage but stepping into a battlefield of adult womanhood. Her stillness and silence throughout, as she neither moves nor sings, render her not an agent of the ritual but its object, a vessel onto which cultural and gendered expectations are inscribed. This sharply contrasts with the fourth movement, where the daughter’s voice is foregrounded and her image anchored at the visual center, moving fluidly in emotional exchange with her mother. There, the girl is heard and seen as a subject in dialogue, whereas in Dressing for the Wedding, the bride-to-be is rendered silent, still, and visually peripheral. If the fourth movement celebrates intergenerational continuity through song, the third reveals the cost of that continuity—the symbolic erasure of the girl’s agency at the threshold of womanhood. This shift in audiovisual emphasis draws attention to the gestural language of the body and voice, and the tensions they hold within ritual and symbolic space.

Both musical and visual gestures are inherently multivalent and context-dependent. As Small (1998, 169) observes, musical gestures, like bodily ones, “can express contradictory meanings simultaneously” and resist the linearity and singularity that language often imposes. This reveals a critical limitation in attempts to translate gesture—whether sonic or visual—into fixed symbolic meaning. In Nu Shu, the interplay of audiovisual elements precisely highlights this tension. The bride’s cry-singing, her bodily posture, and her visual displacement on screen all function as expressive gestures, yet none convey a stable or singular message. These gestures are open, emotionally charged, and unfold across time. Following Small’s notion of musicking as a dynamic and participatory process, such gestures are not simply read or decoded; they are felt and co-constructed by performer and viewer alike. This affirms the performative nature of meaning in Nu Shu and cautions against reducing its sonic and visual language to static cultural signs.

The third and fourth movements thus offer complementary insights into how audiovisual framing both enables and constrains female vocal presence. Whether foregrounded in cry-singing or visually displaced in silence, the female voice in Nu Shu is never neutral; it is shaped through the interplay of image, gesture, and spatial framing, which collectively construct gendered vocal subjectivity. While Tan's audiovisual approach foregrounds subjectivity, ritual, and sonic presence, it also reveals how voice, when mediated through film, can become shaped by external frames of visibility and meaning. Rao’s theory of sonic materiality provides a crucial lens through which to understand this mediation: voice is not merely heard, but embodied, felt, and situated within a specific visual and symbolic economy.

In Nu Shu, the nüshu singers’ voices become at once a site of agency and vulnerability, alive in breath and gesture yet often displaced from narrative control. As previously noted, Tan’s “organic” solution lies not in resolving this tension, but in holding it, allowing the voice to persist as both material resonance and cultural sign. In doing so, Nu Shu invites us to engage in musicking not as passive listeners but as participants implicated in the audiovisual shaping of voice, identity, and meaning.

Conclusion: What Voice Do We Hear, Whose Image Do We See?

I have long been a listener of Tan Dun’s music. Although I was initially moved by Water Rock’n’Roll, that emotional response gradually gave way to critical reflection. I began to recognize how the work’s aesthetic impact was carefully mediated—through choreographed imagery, rewritten lyrics, and a sonic language that bears Tan’s signature style. This realization prompted a shift in my engagement: are we truly hearing the voices of Jiangyong women, or are we witnessing a carefully crafted spectacle of cultural translation? Perhaps both are true.

Tan’s use of pentatonic motifs, gliding stepwise motion, blurred modalities, and theatricalized timbres in Nu Shu, as well as in earlier and later works such as Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000), Fire Ritual (2013), and Prayer and Blessing (2020), reveals a persistent sonic dramaturgy. This “eastern lament” idiom is crafted to evoke ritual memory and feminine sentiment and also raises questions about stylization and authorial voice. It has become a recognizable feature of Tan’s compositional fingerprint. While it resonates emotionally, its stylistic familiarity may blur the cultural and historical specificity of the source material in certain contexts.

As Nu Shu makes clear, Tan Dun’s position as an artist who rose to prominence in the West and as a cultural translator of China complicates how his work navigates competing expectations. Western institutions often call for innovation and global legibility, whereas Chinese cultural discourse emphasizes authenticity and national heritage. In Nu Shu, Tan Dun draws heavily on symbols often seen in official discourse, such as rural landscapes, maternal ritual, and cultural heritage, but does so with sensitivity to affect and audiovisual experience.

Nüshu has long functioned as more than a writing system. As Liu (2004) notes, it is a social and emotional practice, a community bound by kelian [“pitiful” sentiment], where sorrow is not merely endured but transformed into a shared mode of endurance and survival. Once removed from its lived context and incorporated into circuits of cultural production, nüshu risks becoming an aestheticized suffering. Of the eight nüshu singers who participated in Nu Shu, most were later designated as official cultural ambassadors, gaining public visibility and economic support.[14] At the same time, this symbolic visibility is similarly shaped by external frames and narrative expectations, potentially limiting nüshu singers’ capacity for authentic self-expression.

I remain moved by Nu Shu, though that response is deepened through an awareness of mediation and authorship. The work does not simply present “the secret songs of women”; it presents voices and images that have been shaped through intentional processes of translation and aesthetic construction. As emotion becomes sound, and sound becomes spectacle, authorship plays a decisive role in defining what is remembered and how it is expressed. Far from diminishing Nu Shu’s emotional resonance, these considerations invite a more careful mode of listening. The emotions expressed in nüshu are not universal abstractions, but arise from intimate, context-bound lives marked by pain and resilience. We may never fully recover the affective world of these women, but by recognizing the frames that mediate their voices, we move closer to listening with care rather than consuming with distance. Nu Shu moves us, but it also implicates us as witnesses and participants in the ongoing politics of representation.

Notes

[1] In the official title of Tan Dun’s symphony, the transliteration “Nu Shu” is used to represent the term 女书; however, the correct pinyin spelling is nüshu, with an umlaut over the “u.” This omission of the diacritical mark may reflect an intentional artistic choice or a practical decision for broader international accessibility. In this article, Nu Shu (italicized) refers to Tan Dun’s 2013 symphonic work, nüshu (lowercase) refers to a unique female-authored expressive tradition that developed outside of male-dominated literacy in imperial China, and “Nu Shu” in quotation marks reproduces Tan’s own spelling as cited in the second paragraph. These typographic choices are applied consistently to distinguish their respective referents.

[2] A clip of this scene is available in Tan Dun’s Facebook post from July 10, 2016: https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=1094471077230234. In the official version of Nu Shu: The Secret Songs of Women, this material was incorporated as one of the thirteen microfilms and forms part of the work’s concluding movement alongside the orchestra

[3] Jintuo Nü [“golden lump girls”] refers to unmarried daughters who have not yet left their natal homes. The song is commonly used in local bridal lamentation rituals. A recorded version from the Jiangyong community is accessible at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0tab4L1fE9A.

[4] The emergence of nüshu in Jiangyong cannot be understood in isolation from broader patterns of gendered exclusion in Chinese history. Throughout imperial China, women were systematically denied access to formal education and barred from the civil examination system. Literacy, closely tied to Confucian masculinity and bureaucratic ambition, was rarely extended to girls and often actively discouraged within families. Nüshu's' development in Jiangyong resulted from a unique convergence of local conditions: a dialect conducive to phonetic simplification, enduring networks of sworn sisterhood, and ritualized modes of emotional expression. See also Liu 2012, 205–210; Liu 2017, 231; McLaren 2008, 41–44.

[5] BBC Chinese. “Composer Tan Dun Spends 12 Years Documenting China’s Nüshu Culture.” YouTube video, 7:27. Posted July 10, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jaYtrEqStdM.”

[6] Tan Dun. Nu Shu: Secret Songs of Women. Performed by The Philadelphia Orchestra, conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin, with harp soloist Elizabeth Hainen. Video of a 2017 performance at Verizon Hall, Philadelphia; broadcast February 4–11, 2021, as part of the orchestra’s virtual Lunar New Year Celebration. Hosted by Tan Dun. This recording, which includes all thirteen microfilms, is the primary audiovisual source for all analyses in this article.

[7] In this article, I use the terms bridal laments, kuge, and cry-singing interchangeably to refer to a ritualized female vocal expression performed by brides in Jiangyong County before marriage. As Fei-Wen Liu (2012) explains, kuge is a subgenre of nüge [women’s folk songs] and is closely integrated with the practice of nüshu. While nüge encompasses a broader repertoire of women’s songs, kuge specifically denotes the emotionally charged lamentations associated with wedding ceremonies. See Liu 2012, 209–210.

[8] Judith Butler argues that public grief is not distributed equally across social groups. In her view, some lives are more “grievable” than others because they are already recognized as valuable by dominant cultural systems—such as heterosexual, male, or nationally normative lives. Marginalized identities, including women, queer individuals, or racial minorities, are often excluded from the public discourse of mourning (Butler 2004, 22–25).

[9] A televised 2011 performance of the bridal lament Zexi Reqi on China Central Television offers a glimpse of this aestheticization: a group of elderly women sing in strong, penetrating voices while the performer portraying the bride remains silent, leaning into the arms of a companion throughout. Only after the song ends does she rise, turn to face the camera, and reveal her traditional bridal attire. This performance aired as part of the CCTV program Minyue Zhongguo (Folk Music China), a state-run variety series featuring traditional Chinese folk music. Aired on CCTV-3 on May 17, 2011.The video is available at: https://tv.cctv.com/2011/05/17/VIDE1372406011931728.shtml?spm=C53173422422.PQMDeF09pGwu.0.0

[10] The thirteen microfilms in Nu Shu are titled: Secret Fans, Mother’s Song, Dressing for the Wedding, Cry-Singing for Marriage, Nu Shu Village, Longing for Her Sister, A Road Without End, Forever Sisters, Daughter’s River, Grandmother’s Echo, The Book of Tears, Soul Bridge, and Water Rock’n Roll (Tan 2013).

[11] Similar practices can be found in the works of John Cage (“found objects”), Harry Partch (corporeal instruments made from natural materials), and Pauline Oliveros (environmental sound and deep listening), all of whom integrate natural or non-instrumental materials into compositional processes.

[12] In Rao’s framework, materials are not passive vehicles of sound but agentive media with sensory, cultural, and behavioral tendencies. In Tea, for instance, paper does not merely emit sound when torn; its fragility, transience, and ritual associations actively shape the sonic and symbolic dimensions of the performance. The material properties of paper thus conditions what kinds of meaning and affect can emerge—this is what Rao refers to as the “subjectivity” of materials.

[13] In Chinese pentatonic theory, jue (角) corresponds roughly to scale degree 3, and yu (羽) to scale degree 6. The yu mode (羽调式) emphasizes yu as the final and tonal center, often creating a descending and introspective quality.

[14] As of May 2024, public reporting in Chinese-language media indicates that seven of the eight nüshu singers involved in Nu Shu have become either official or grassroots cultural ambassadors. Their activities are regularly featured in regional heritage promotions and public events (see Xinhuanet 2024): http://www.news.cn/gongyi/20240511/1393ff56e2d34940a17b0e2c7875e93a/c.html

References

Butler, Judith. 2004. Undoing Gender. Routledge.

Dyall, Felicity. 2023. “The Harp, Ireland and Irish Harp Music.” All-Ireland Cultural Society of Oregon. Accessed May 15, 2025. https://oregonirishsociety.org/the-harp-ireland-and-irish-harp-music-by-felicity-dyall/.

Liu, Fei-Wen. 2004. “From Being to Becoming: Nüshu and Sentiments in a Chinese Rural Community.” American Ethnologist 31 (3): 422-439.

Liu, Fei-Wen. 2012. “Expressive Depths: Dialogic Performance of Bridal Lamentation in Rural South China.” The Journal of American Folklore 125 (496): 204–225.

Liu, Fei-Wen. 2017. “Practice and Cultural Politics of ‘Women’s Script’: Nüshu as an Endangered Heritage in Contemporary China.” Angelaki: Journal of Theoretical Humanities 22 (1): 231-246.

Irigaray, Luce. 1985. This Sex Which Is Not One. Translated by Catherine Porter. Cornell University Press.

McLaren, Anne E. 2008. Performing Grief: Bridal Laments in Rural China. University of Hawai'i Press.

Qian, Renping, ed. 2015. China New Music Yearbook. Shanghai Conservatory of Music Press.

Rao, Nancy Yunhwa. 2023. “Materiality of Sonic Imagery: On Analysis of Contemporary Chinese Compositions.” Music Theory Spectrum 45 (1): 151-155.

Small, Christopher. 1998. Musicking: The Meaning of Performance and Listening. Wesleyan University Press.

Spiller, Henry. 2019. “A Queer Organology of the Pedal Harp.” Women and Music: A Journal of Gender and Culture 23 (1): 25–43.

Tan, Dun. 2013. Nu Shu: The Secret Songs of Women – Symphony for Harp, 13 Micro Films, and Orchestra. Wise Music Classical. Accessed April 6, 2025. https://www.wisemusicclassical.com/work/48098/Nu-Shu-The-Secret-Songs-of-Women---Symphony-for-harp-13-micro-films-and-orchestra--Tan-Dun/.

Titon, Jeff Todd. 2008. “Knowing Fieldwork.” In Shadows in the Field: New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology, edited by Gregory Barz and Timothy J. Cooley, 25–41. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Xiang, Jinyun, and Xiang Xiuyun. 2021. Wailing Songs at Weddings. Collected and edited by Xiang Daiyuan and Xiao Benzheng. Translated by Cai Wei. Wuhan: Wuhan University Press.