“Today You Have to Study All of These Ritmos”: Negotiating the Curriculum in the Didactization of the Brazilian Pandeiro

Johannes Nilles

University of Music and Theatre Munich

Lecturer and Associated Researcher, University of CologneThis paper examines the didactization of the pandeiro in international teaching-learning contexts, its transformation into a teaching object. Although this Brazilian frame drum has similarities with instruments in various musical cultures from the Arab world to the Iberian Peninsula (Araújo 2019, 8; Pinto and Laade 1991, 138), there are specific differences in learning the Brazilian variant. In this paper, I argue that international students in the historic city center of Salvador have a significant impact on its curriculum's structure, which is organized according to musical genres, or ritmos. This article demonstrates how this comes about and points out the ambivalence of this tendency.

The title quote stems from pandeiro teacher Bira Santos emphasizing the importance of ritmos in pandeiro learning (Santos, interview with author, September 21, 2023). The article starts by defining this term, which means more than its literal translation to rhythm, and outlines its usage during my fieldwork in Salvador da Bahia.[1] Three hypotheses on the cause of ritmo-orientation are presented, followed by a concluding reflection on the impact of European learners and myself on teaching-learning situations in the historical center of Salvador. The field notes and interview statements are based on my fieldwork in Salvador da Bahia and Lisbon between 2022 and 2023, during which I took classes as a pandeiro learner.

As a white person with an obvious German accent in Portuguese, I am inevitably read as European, which in the field is associated with attributions of wealth and the chance to travel the world. Furthermore, I am part of an “international percussion community” interested in the pandeiro (see Potts 2012, i), which constitutes a considerable percentage of the student body in the historic center of Salvador and thus fosters the pandeiro’s didacticization. Beyond my own case, there is a general economic dependency between teachers and the group of foreign students that influences how I am perceived. I strive to consistently reflect on this power dynamic in my analysis.

RITMO-STRUCTURING IN PANDEIRO LESSONS

In Bahian pandeiro teaching contexts, ritmo refers most closely to genre or musical style, sometimes even musical tradition, such as the maracatu or the samba de coco. This use of the term can also be found among my interview partners: when pandeiro teacher João Lima announces that he will be teaching the four ritmos, including coco, samba, baião and ijexá, he is mainly referring to musical styles. These are introduced using a prototype pattern, which is later varied by single strokes. When Lima says that he has mastered twenty ritmos, he is not referring to twenty different rhythms of the same genre, but to the number of styles he uses. For example, Lima offers three different variations of the samba de coco’s final bass strokes.

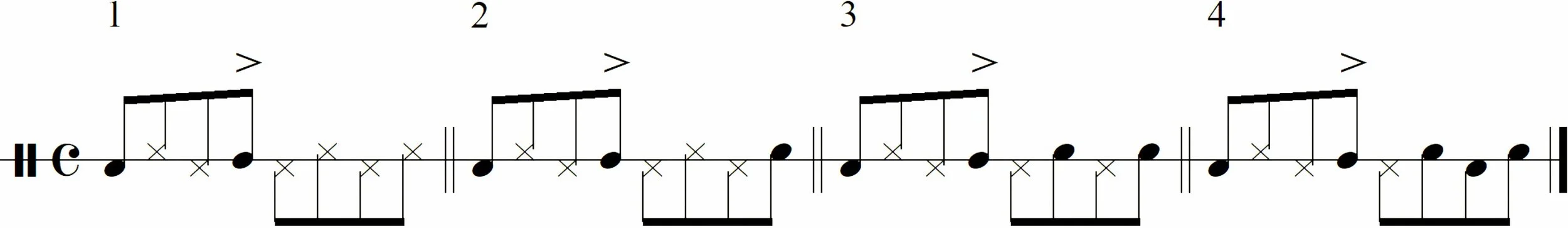

Figure 1: Samba de Coco prototype pattern (1) and Variations (2-4) as taught by João Lima (field notes, October 31, 2023); simple note heads are played as bass strokes, accents as slaps and sharps as jingles.

These variations within a single ritmo could be observed across all teachers as well as all genres (ritmos). In contrast to Lima’s use of the term ritmo is that of Italian pandeiro student Francesco Manca: “And you can play any kind of genre with pandeiro” (Manca, interview with author, April 2, 2023). He is using the word genre.

What might make pandeiro teachers talk about ritmos instead could be the centrality of rhythmic structures to a genre in Brazilian popular music. José Gallego Colomer, Spanish guitarist and student of Lima, says:

I think [the pandeiro] might be better to distinguish [than the guitar]. Because with the pandeiro it's more like just playing the markers. And that's like more the most basic structure of the song, because at the end with the chords I've already played xote and I’ve already played baião and at the end they can be the same simple chords (Gallego Colomer, interview with author, November 6, 2023).

From his perspective as a guitarist, many Brazilian musical styles may be played similarly. It is in fact percussion instruments such as the pandeiro, which are primarily used for rhythm, that set each genre apart. Gallego Colomer highlights the importance of rhythm in characterizing and differentiating musical genres. In this article, the Portuguese word ritmo will be used to refer to the different Brazilian music genres.

The ritmos do not appear to be a fixed canon. Each teacher offers a different repertoire of ritmos. Some of them are covered by all participating teachers, while others are very individual and only appear in a single course.

FURTHER PANDEIRO LEARNING COMPLEXITIES

Knowledge of numerous ritmos repeatedly appears to be a characteristic of a good teacher. Although other skills such as good technique are also frequently mentioned in interviews, the long list of ritmos on the wall of Maestro Macambira’s music school demonstrates that they are ultimately the most important aspect of teaching pandeiro.

As soon as we met, João Lima told me about twenty ritmos that he teaches. However, Lima and other teachers emphasized repeatedly that lessons should not just be about learning ritmos (field notes, October 31, 2023). He quoted the famous YouTube teacher Léo Rodrigues, who had emphasized this shortly before in his workshop in Salvador. My interviewees also formulated the demand to work on technique. For the local pandeiro teacher Bira Santos, among others, ritmo is just one of several components of learning: “First, I review the sound techniques of how to produce them, then I work on the groove and then at the end I work on the ritmo, right?” (Santos, interview with author, September 21, 2023).

There is also the challenge of the typical phrasing, the balanço (Gerischer 2006; Bystron 2018), which is significantly influenced by left hand rotation. Nevertheless, I noticed the ritmos structuring the curriculum in all the teaching-learning situations I researched in the historical center of Salvador. Teachers such as João Lima or Maestro Macambira do not list the playing techniques they teach right at the beginning. Most teachers also limit themselves to a manageable number of sounds they teach such as the bass stroke, slap, and tap. Even though technique and sound were mentioned again and again, the structure of most of the lessons was dominated by the orientation towards ritmos.

THREE HYPOTHESES

In the following, I would like to put forward three hypotheses as to why this ritmo-structuring occurs, especially in an international context, in which individuals travel to Salvador to learn the pandeiro.

1. Didactic reduction: I employ Martin Lehner's (2012) concept of “didactic reduction” to explain the focus on ritmo-structuring. Teaching and learning a new ritmo is a complex challenge that, as mentioned by my interviewees, involves learning the (sound) techniques and the groove. When using the extended concept of ritmo as an entire genre with historical, emotional, and political dimensions, the need for its reduction in complexity in order to facilitate its teaching becomes apparent. This is particularly necessary for traveling learners who only learn for a short time and predominantly in non-formal lessons.

Teachers therefore apply didactic reduction. According to Lehner, this involves reducing the complexity of the teaching content.

On the one hand, this means concentrating on the essentials, i.e. on the terms, concepts, statements, experiences and structures that are essential for the target group, and on the other hand, simplifying what is complicated—for this target group—into comprehensible learning elements (Lehner 2012, 121).

In this case, the result is an emphasis on what is distinctive. Although the work of the left hand is inevitably part of the ritmo, in many cases it results from the stroke sequences of the right hand. The right hand playing a sequence of bass stroke, slap, and tap is therefore more distinctive and, in this sense, more essential.

Didactic reduction does not only concern international learners, but is a general didactic concept. However, the special framework conditions of traveling learners reinforce this effect of didacticization and thus shape the entire teaching-learning situation.

2. Learners’ epistemologies emphasizing the writable: The epistemological perspectives of western learners tend to emphasize the writable, the explicable rhythmic patterns. Bira Santos’ above-mentioned learning areas, technique and sound, are difficult to fix in writing. The inadequacy of language seems even more obvious when it comes to shaping sounds. Along with the balanço, the characteristic microtiming, these are qualities that cannot be fully represented in written form. Learning to produce a bass tone with the middle finger requires acoustic and tactile feedback from the instrument and a precise idea of the sound. The embodied, tacit knowledge (Polanyi 1985) of this technique goes far beyond a description of the movement.

In contrast to this, although the ritmos have complex meanings, they can be introduced with a prototypical pattern (as mentioned above), a sequence of beats that can be described in a few sentences. Therefore, they are an aspect of music that can be written down well in this form.

In Epistemologies of the South (Santos and Meneses 2009, 9-10), sociologist Boaventura de Sousa Santos refers to culturally different “rival” ways of producing knowledge that have been historically marginalized by the Western world in favor of a universal epistemology. The “occidental” perspective is often described as analytical and theorizing or as emphasizing the written (Bessa 2022, 88). Against this background, the emphasis on what can be written down can be understood as a consequence of traveling learners’ occidental, theorizing ways of knowledge-making.

Learners who are consciously or unconsciously in search of writable knowledge, whose learning style is characterized in this way, influence learning opportunities by their inquiries. The ritmo-orientation observed in pandeiro lessons can therefore be understood as a consequence of the learners' epistemologies emphasizing the writable.

3. Learners’ categorizing inquiries: A third point emerged from a question and answer session towards the end of João Lima‘s lesson. Pandeiro student José, one of my interviewees, immediately wanted to know how the ritmo forró is played (field notes, October 31, 2023). He already knew a beat sequence from Léo Rodrigues on the internet but had picked up other patterns under this term. Against this background, it does not seem to be an independent decision on the part of the teacher, but rather that lessons are structured according to ritmos, based on the needs of the learners. When traveling learners such as José or myself come to Bahia, take pandeiro lessons there and ask for specific ritmos with specific expectations, it seems only logical that the lessons on offer should be adapted accordingly. In my first pandeiro lesson with Bira Santos, I asked for the Cabila, which I had once heard about at a workshop (field notes, February 24, 2022).

In this context, João Lima’s statement that ritmos were historically undefined in their distinct form, but that this clear classification only came later, gains significance (field notes, October 31, 2023). The external perspective on regional music practices makes labeling necessary. A genre needs a name in order to communicate learning content. The naming of definable ritmos appears here as a result of categorizing inquiries and thus as a consequence of globalization and didactization, of pandeiro becoming a teaching object. This means that the music played is named externally and subsequently verbalized in teaching-learning situations. The naming leads to categorization. This phenomenon is intensified when local learners prioritize questions from international learners, as “they are likely to depart soon” (personal communication, October 31, 2023) as I was once told by another student.

CONCLUSION

Pandeiro teaching-learning situations in Brazil are significantly shaped by traveling learners, resulting in the structuring of learning content according to ritmos (in this case, genres). This is due to (1) didactic reduction, (2) learners’ epistemologies emphasizing the writable and (3) learners’ categorizing inquiries. This influence exposes the problems of existing power relations, especially as the presence of foreign learners results in a decrease in the influence of local learners. However, local learners also have a global perspective on music practices and therefore contribute to a certain extent to the three effects described in this paper. An overall ethical evaluation of pandeiro learning in the historical center of Salvador must also take into account that foreign learners facilitate a flourishing scene of professional percussion and pandeiro teaching. With this analysis, I hope to have shed some light on the ambivalent influences of the international percussion community in the historic center of Salvador da Bahia.

NOTES

[1]All translations by author unless otherwise specified.

LIST OF INTERVIEWS

Bira Santos, interview by author, Salvador da Bahia, September 21, 2023.

Francesco Manca, interview by author, Lisbon, April 2, 2023.

José Gallego Colomer, interview by author, Salvador da Bahia, November 6, 2023.

DECLARATION OF CONSENT OF THE QUOTED PERSONS

All individuals quoted in this article are participants in my doctoral research project. They have received information about the project and have consented to its terms. In addition, the named individuals have explicitly agreed to the use of their statements in this article.

REFERENCES

Araújo, João. 2019. Pandeiro Workshop. Heroldsbach: Girabrasil UG.

Bystron, Janco Boy. 2018. Brasilianische Grooves. Makro- und Mikrostrukturen brasilianischer Percussionsmusik im soziodynamischen Kontext. Berlin: epubli.

Gerischer, Christiane. 2006. “O Suingue Baiano. Rhythmic Feeling and Microrhythmic Phenomena in Brazilian Percussion.“ Ethnomusicology 50 (1): 99-119.

Lehner, Martin. 2012. Didaktische Reduktion. Bern: Haupt.

Pinto, Tiago de Oliveira, and Wolfgang Laade. 1991. Capoeira, Samba, Candomblé: Afro-brasilianische Musik im Reconcavo, Bahia. Berlin: Museum für Völkerkunde.

Polanyi, Michael. 1985. Implizites Wissen. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Potts, Brian James. 2012. Marcos Suzano and the Amplified Pandeiro: Techniques for Nontraditional Performance. Miami: University of Miami.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa, and Maria P. Meneses. 2009. Epistemologias do Sul. Coimbra: Edições Almedina.

Bessa, Beatriz de Souza. 2022. “Artes Musicais Indígenas Africanas Em Sala De Aula. A contribuição de Meki Nzewi.“ Áskesis 10 (1): 79-96.