Ethnomusicological Research of the Press and Personal Journals in Historical Periods of Political Conflict: Challenge or Opportunity?

Argyrios Kokoris

PhD, EthnomusicologyAristotle University of ThessalonikiThe research work was supported by the Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation (H.F.R.I.) under the 3rd Call for H.F.R.I. PhD Fellowships (Fellowship Number: 5393).

This article centers on methodological concerns pertaining to the investigation of auditory and musical records in historical texts of times of sociopolitical conflict, with a particular emphasis on personal journals and diaries of contemporary intellectuals and early twentieth-century daily press.[1] Following the completion of my doctoral research on the National Schism of Modern Greek Political History (1915–1922),[2] my objective was to evaluate these records by scrutinizing the theoretical and methodological issues inherent in historical ethnomusicological research of the same nature. This investigation was driven by a research interest stemming from the press’s credibility as a primary source of ethnographic material. The importance of this component should be overstated for a historical ethnomusicologist who investigates periods of “trouble” (Rice 2017). During a period marked by persistent censorship and propaganda, my research stimulated inquiries into the archived press’s ability to uncover textual representations of musical expression that address this enormous political conflict that evolved into a protracted civil war. Investigations into these accounts have also provoked interest into how such textual representations, mandated by the ruling party, distorted, selectively presented, or disregarded the auditory presence of the subaltern party.

The subsequent inquiries and research contributions provide thought-provoking insights into the power dynamics and hierarchical structures that were prominent during the Schism, as manifested in the polarized political press of the two parties. Despite facing censorship and propaganda on a continuous basis, this press managed to preserve political expressive cultural traits of the everyday urban music and sound sphere in its columns and chronicles. This allusion is also applicable to personal diaries that were contingent on particular cultural and political perspectives of their writers.[3] This type of investigation intends to reexamine the theoretical framework of the music-power nexus. This entails a holistic interpretation of music that makes use of elements and tools such as soundscape, noise, and silenced voices. Specifically, I examine silence literally and metaphorically in the context of political repression and archival omission, pushing for a reassessment of historical ethnomusicological thought within auditory history.

NOISE AND THE SOUNDSCAPE: AN ATTEMPT TO REDEFINE HISTORICAL ETHNOMUSICOLOGICAL THOUGHT

Ethnomusicological communities are becoming increasingly involved in studies concerning the connection between conflict and music (see for example O’Connell and Castelo-Branco 2010, Ritter and Daughtry 2007). The interdisciplinary study of conflict emerged as an independent academic discipline in the latter half of the twentieth century, drawing inspiration from political science, psychology, sociology, and anthropology, among others (Grant et al. 2010). Conflict is presently a distinct and specialized area of investigation for ethnomusicologists, wherein the study of music can contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of politics (O’Connell 2010). This is, in essence, established in the tenets derived from seminal ethnomusicological texts, which assert that music and its connotations are influenced and molded by other cultural spheres (Berger 2008, 72). Among these spheres, the political is an intimately and multidimensionally intertwined domain with which music is inextricably linked, as stated in Nili Belkind’s latest monograph (2021, 12). Belkind (2021, 242–43) explains that anthropology employs expressive culture to illuminate the ways in which boundaries are reshaped and reflected in the midst of political conflicts, via the increased prevalence of music in the public sphere. Prior to Belkind’s assertion, ethnomusicologist Maureen Mahon (2014, 327) states that “through engagement with expressive culture people respond to and deal with ‘real politics’ and ‘real issues.’” Following on such a direction of an ethnomusicology of conflict in general, Timothy Rice (2017, 240) observes that “our studies of music in times and places of violence and war will lead us to broaden the scope of our studies to the sonic environment in which musical life occurs”, thus proposing a new sub-discipline, which he calls “ethnosonicology” (2017, 250).

In contemporary studies, the redefinition of music as noise and sound is essential (Feld 2017), intriguing scholars who are interested in the nexus of music and politics (Garratt 2019; Street 2012). The overarching objective of this contemplation is “a reconsideration of the taxonomies allowing us to think/not think about music and power” (Wong 2014, 350). Consequently, music is now regarded as a component of a broader phenomenon known as cultural noise, as Wong (2014, 351) and Sterne (2012) further explicate. This holistic notion validates current tendencies in ethnomusicological literature that situate sound and voice as a “neighborhood” within the broader conceptual domains of resonance, listening, vibration, and mediation (Meizel and Daughtry 2019). Nevertheless, the precise identification of sounds that qualify as music is contingent upon interpretive frameworks. These frameworks emphasize the significance of the listening process, which transcends mere auditory reception and encompasses cultural and historical influences, that also cross race and gender; it is a collaborative endeavor involving both individuals and groups (Meizel and Daughtry 2019, 176; cf. Wong 2017).

But how can these notions be applied to the research of the past? According to the principles of auditory history, among others, historians use dissonance and noise to indicate social and cultural differences. This transition frees historical discourse from an overly narrow focus on vision by redefining the past as a holistic sensorial experience (see for instance Smith 2007; 2004). By critically listening to the past and paying attention to multisensory experience, the soundscape may illuminate the history and politics nexus. David Samuels and his colleagues assert that “an anthropology that engages more seriously with its own history as a sounded discipline and advances in ways that incorporate the social and cultural sounded world more fully” is critical for the reinterpretation of the past and its social and cultural dimensions (Samuels et al. 2010, abstract); it serves to orient individuals in space and time, shape experiences, and communicate.

Noise is a key element that can enhance the specific application of the soundscape into such research. The power of noise as a material sound form and as a label imposed on the soundscape —both of which have profound cultural implications for urban life and politics— is utilized to capture the element of contradistinction in diverse contexts throughout such texts. For instance, through an examination of texts from early colonial America, Ochoa Gautier (2014) illustrates how Western listeners portrayed Indigenous voices as untamed and unruly, necessitating the intervention of Europeans to civilize them. This alludes to the critical assessment per post-colonial scholarship that certain voices are accorded greater weight and prominence than others on the basis of their placements along the sonic color and gender lines (see Stoever 2016) while also elaborating on the “many nuanced associations of voice with power and agency” (Meizel and Daughtry 2019, 192–3).

History, nevertheless, through the lens of the acoustic past, seeks to understand social and political oppositions and hierarchies by analyzing sound sources preserved in historical documents. Daniel Bander, Duane J. Corpis, and Daniel J. Walkovitz (2015) argue that sound is a component of the broader sensibility (a soundscape) and subject to interpretation, negotiation, definition, contestation, and discipline. However, the nuance and unpredictability of sound must perpetually be considered, in part because of the varying personal contexts of the audience. Undoubtedly, sound and its related concepts, such as noise and soundscape, consistently play a central role in conversations that encompass music and politics, particularly in historical investigations, paving the way for a new historical ethnomusicological theoretical foundation. This notion is yet to be explored in this emerging and intriguing new direction, which has the potential to facilitate the discernment of a holistic understanding of politics and conflict through music; this could possibly advance the interdisciplinarity and interactivity of ethnomusicology as a mediator to reveal and comprehend historical and/or political conditions that were otherwise or previously obscure; in the next section I argue that this is achievable through the careful examination and research of historical textual accounts, including the press and personal diaries preserved in archives.

RESEARCHING WITHIN TEXTUAL ACCOUNTS OF THE PAST: THE PRESS AND PERSONAL DIARIES

The press is an invaluable source of primary historical material and a valuable research tool, offering global perspectives on human events by reflecting the “real” society and time of circulation in the newspaper’s country or city—if examined cautiously, as I elaborate further down. Material found in multiple columns of circulated papers provides insights into social groups through individual manifestations of routinary or extraordinary activities. Press articles and data can be used to gather specific information over time rather than in one viewing. Supplementally, personal journals/diaries may reveal sonic and auditory perceptions that other textual descriptions miss. After taking the political, social, ideological, and overall cultural attitude of the people who wrote them under consideration, these textual accounts should be considered primary material sources. Philip Bohlman’s approach to the musical past “as a narrative space” is notable in such research (2008, 261–263). Bohlman (2008, 261) observes, with reference to literary theorist Edward Said, that “the stories told in the past cannot escape the political connections to the world around them” (Said 1993, 62–80). In a journalistic space that is constituted by the emergence from a multilayered political conflict, one must therefore proceed with extreme caution when examining it within a narrative sequence dominated by political fanaticism and polarization.

A careful and critical investigation of the press and personal journals/diaries can reveal aspects of expressive culture in popular music during political turmoil. This applies to specialized pieces, chronicles, and columns. Named chronographs are crucial to this research because they function as quasi-ethnographies, sometimes giving the impression that they were written by fellow “ethnographers” researching the historical period under investigation. William Noll (1997) calls them “silent partners” who illuminate important aspects of the historical period through their timely, vital texts. Written sources, especially the politically biased or censored press, present methodological, interpretational, and analytical challenges that lead to insufficient evidence. Furthermore, one must take into consideration the sociopolitical background of the events and the elitist or “exoticist” mindset of the writers of that time (Kitsios 2020). This research can be used as primary source material for an ethnographic analysis of the period in order to comprehend power dynamics and political hierarchies, reevaluating the relationship between music and politics (see related ethnomusicological discussions in Berger and Stone 2019; Berger 2014; Mahon 2014).

In such accounts, distinguishing the voices of the “other,” that have been “silenced” or “lost,” may be among the most formidable obstacles for the researcher. This awareness alludes to the archival challenge, which involves the crucial task of reconstructing historical narratives that have emerged as a result of colonial imperialism. Following such contemporary post-colonial studies as Ann Laura Stoler’s (2009) seminal historical ethnography on colonial archives, ethnomusicologists have attempted to address “the disjunctures of colonialism, followed by the labor invested in retrieving voices lost to history” (Bohlman 2013, 18). Nevertheless, postcolonial scholarship has encountered criticism regarding methodology. When dealing with literal and figurative silences, “many interpretative methodologies from the social sciences are not suited to understand the different layers of silences that are relevant to archival research” (Decker 2013, 169). Such “layers of silence” may conversely relate to the many “layers of historical understanding,” that Hebert and McCollum (2014, 99) discuss, suggesting that we need to take “into account multiple voices as well as the reasons that interpretations change across time,” or as Bohlman (2008, 249) defines as “ethnomusicological pasts.”

My doctoral research on the National Schism (1915–1922) of Modern Greek History confirmed such assumptions, regarding collective party trauma and memory that stem from such misrepresentations in historical accounts. As actions of one ruling political party in the years 1917–1920 (Venizelism), which imposed and dominated over the opposing political party (Antivenizelism), the latter’s “voice” and expressive ability was relentlessly constrained at the time; this was in accordance with the state policy implemented during the Venizelos administration, which involved the suspension of constitutional liberties and martial law.

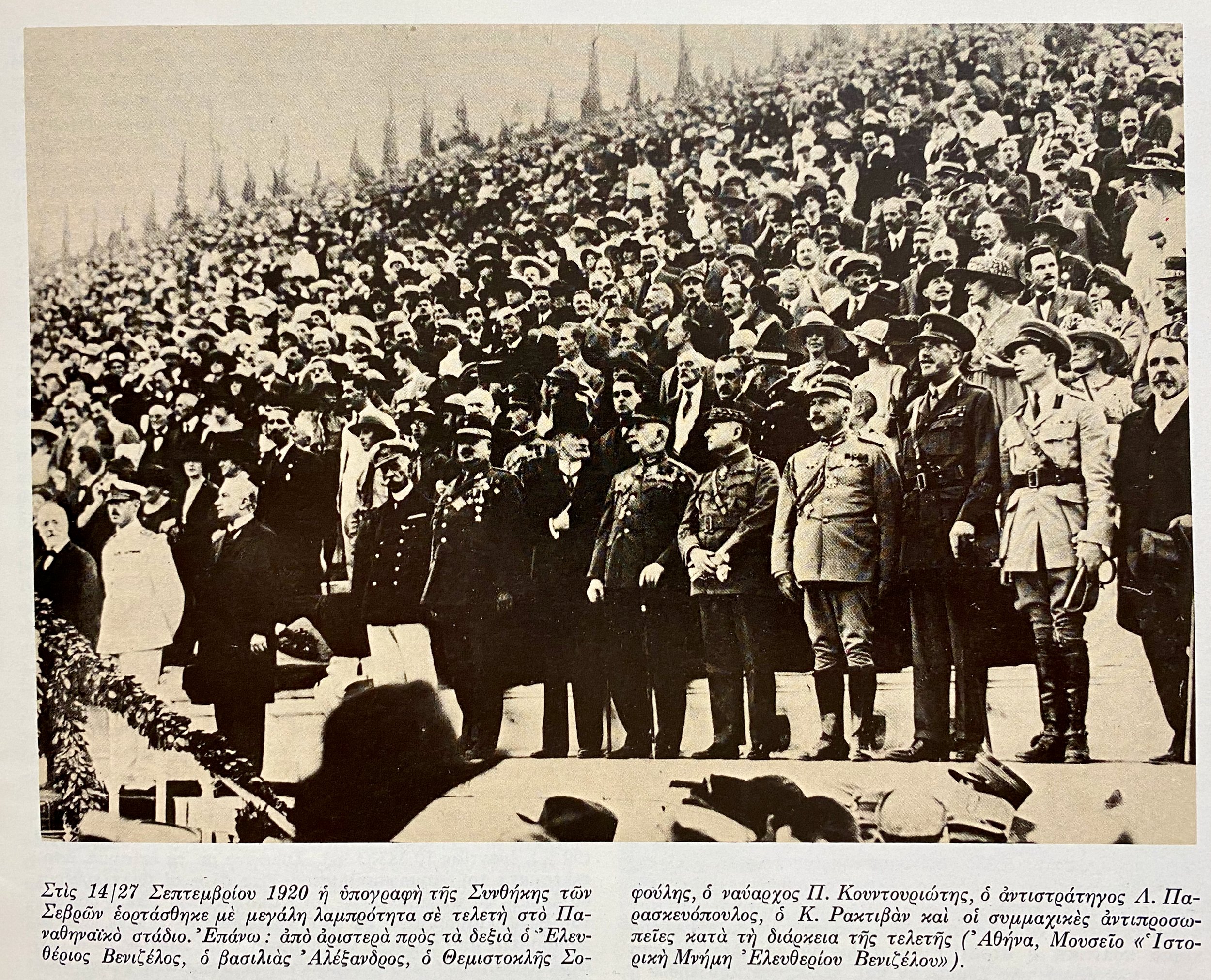

Figure 1. Caption of the Stadium festivities of 14/27 September 1920, celebrating the Treaty of Sevres (July 28/August 10, 1920). Prime minister Venizelos is depicted on the very left of the picture, while next to him is King Alexander I’ (King Constantine’s second-born son, who was to be bit by a monkey and die from sepsis only three weeks later). Under the picture are listed the names of the Venizelist government officials depicted in the front row next to Venizelos. History of the Hellenic Nation 2000, XV':149.

One example portraying such assertions is the September 14/27 and 15/28, 1920 festivities held by the Venizelist government in Athens, with staged musical performances and deliberate efforts to promote a unified, national culture. These public performances commemorated the Treaty of Sevres (July 28/August 10, 1920), a national victory attributed to Venizelos, and the Venizelist party’s ideological and diplomatic ambitions. Investigations conducted in the popular press of the era, primarily through interpretative discourse analysis of major articles, unveiled the manner in which the Venizelist government orchestrated and presented these September festivities through the imposition of mass acceptance; this transpired notwithstanding the oppositional faction’s substantial support base among the Athenian populace (“Enomene Antipolitefsis”—Unified Opposition). As Antivenizelist newspapers bravely reported during the days of the festivities, Venizelos’s “charismatic”, yet sinister, leadership was demonstrated by his personal attendance of ceremonies and galas in Athens as his henchmen forced opposers to cheer for him and sing his personal anthem in the streets of Athens. In spite of martial law prohibiting Antivenizelist political musical expression, specifically any performance of Venizelos’s rival and exiled King Constantine’s personal anthem “Aetos” (the Eagle), some mass-performed acts of resistance can be located in the Antivenizelist press. Additional manifestations of resistance were also documented in the Venizelist press; these instances of popular resistance, such as Antivenizelists chanting rhythmically against the “Venizelist Tyranny,” were labeled as disruptive noise that necessitated suppression and silence in order to preserve the unity of the nation, as perceived and projected by the Venizelists.

CONCLUSIONS

Undertaking an analysis of historical ethnographic accounts proves to be arduous. Researchers often encounter obstacles as they endeavor to discern the silent voices of suppressed individuals, whose musical, vocal, and sonic imprints have been meticulously documented in written texts, while also listening to them critically. However, I argue that combining an extensive historical awareness of the sociopolitical circumstances of the time period with these documents expands on present day research. In my research on the early twentieth-century Greek National Schism, these ethnographic texts elucidate the press’s extreme political polarization and intellectuals’ personal journals/diaries. By overcoming the methodological and theoretical challenges of researching texts that allude to political polarization, silenced voices and the writers’ specific cultural and/or elitist —and sometimes “exotic”— mindset, a researcher can undoubtedly construct an ethnographic representation that offers insightful observations. This representation should not only pertain to the subject matter being investigated but also the theoretical underpinnings of ethnomusicological inquiries conducted during “troubled” periods and locations in the past, and particularly during political unrest and civil strife.

NOTES

[1] I use the term “press” as any printed publication that was regularly distributed to the public for the purpose of providing information and entertainment. This refers to the primary written sources of mass media distributed during that period, namely newspapers and magazines.

[2] The “National Schism” is a sociopolitical phenomenon that consolidated between two rival “charismatic parties” in the Greek society in 1915–1916, Venizelism and Antivenizelism, and whose consequences marked permanently the Greek political and social history, especially during the inter–war period 1922–1936. In a short historical debriefing, the Schism’s ignition dates back to February 1915, when disagreement between Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos and King Constantine I’ broke out on whether Greece should enter World War I on the Allies side (Venizelos’ wish) or remain neutral (Constantine’s demand). Following recent mass political assessment of the phenomenon, it has been characterized as a fascinating Weberian scenario of “charismatic” civil conflict between two “charismatic” leaders, Eleftherios Venizelos and King Constantine I’ that generated two opposing antagonizing mass power movements known as Venizelism and Antivenizelism respectively (see Mavrogordatos 1983 and 2015). In my research I have made use of Mavrogordatos’ hermeneutical model of mass political theory to interpret and analyze musical and auditory expressive cultural traits in references of the press and other textual accounts; these two warring parties employed song, vocal chants and the soundscape to generate mass psychological phenomena, which I have located in the press within the peak year of the civil conflict in Athens, 1920.

[3] Indicatively, the personal diary of the Venizelist authoress—and personal friend of Venizelos himself—Penelope St. Delta (1978), is quite enlightening; she witnessed and experienced the events of the Antivenizelist retaliation and government (1920–1922) that involved vengeful mass rhythmically performed chants and impromptu lyrical alterations on popular songs of the time that claimed to cleanse Athens from the Venizelist “plague” (1917–1920), and noting down the general mayhem of the time in terms of the urban soundscape that generated mass psychological phenomena from the two conflicting parties, especially during the events of the National Elections of November 1, 1920. Due to her noting lyrics in the diary, it can be also perceived as a song notebook, and therefore as a “genuine” historical ethnomusicological source (see Burstyn 2017).

REFERENCES

Anonymous, 1920. “Venizelism attempts to terrorize / The hordes of the mobsters.” Politeia, 15 September.

Belkind, Nili. 2021. Music in Conflict: Palestine, Israel and the Politics of Aesthetic Production. London: Routledge.

Bender, Daniel, Duane J. Corpis, and Daniel J. Walkowitz, eds. 2015. “Sound Politics: Critically Listening to the Past.” Radical History Review (121).

Berger, Harris M. 2008. “Phenomenology and the Ethnography of Popular Music: Ethnomusicology at the Juncture of Cultural Studies and Folklore.” In Shadows in the Field: New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology, edited by Gregory F. Barz and Timothy J. Cooley, 2nd ed., 62–75. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

———. 2014. “Call and Response: Music, Power, and the Ethnomusicological Study of Politics and Culture: ‘New Directions for Ethnomusicological Research into the Politics of Music and Culture: Issues, Projects, and Programs.’” Ethnomusicology 58 (2): 315–20.

Berger, Harris M., and Ruth Stone. 2019. “Introduction.” In Theory for Ethnomusicology: Histories, Conversations, Insights, edited by Harris M. Berger and Ruth Stone, 1–25. New York: Routledge.

Bohlman, Philip V. 2008. “Returning to the Ethnomusicological Past.” In Shadows in the Field: New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology, edited by Gregory F. Barz and Timothy J. Cooley, 2nd ed., 246–70. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

———. 2013. ‘Introduction: World Music’s Histories’. In The Cambridge History of World Music, edited by Philip V. Bohlman, 1–20. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Burstyn, Shai. 2017. “Remarks on Israeli Song Notebooks.” In Historical Sources of Ethnomusicology in Contemporary Debate, edited by Susanne Ziegler, Ingrid Åkesson, Gerda Lechleitner, and Susana Sardo, 130–43. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Decker, Stephanie. 2013. “The Silence of the Archives: Business History, Post-Colonialism and Archival Ethnography.” Management & Organizational History 8 (2): 155–73.

Delta, Penelope St. (Δέλτα, Πηνελόπη Στ.). 1978. Ελευθέριος Κ. Βενιζέλος: Ημερολόγιο, Αναμνήσεις, Μαρτυρίες, Αλληλογραφία [Eleftherios K. Venizelos: Diary, Memories, Testimonies, Correspondence]. Edited by Pavlos A. Zannas. Archive of P. S. Delta. Athens: Hermes.

Feld, Steven. 2017. “On Post-Ethnomusicology Alternatives: Acoustemology.” In Perspectives on a 21st-Century Comparative Musicology: Ethnomusicology or Transcultural Musicology?, edited by Francesco Giannattasio and Giovanni Guiriati, 82–98. Udine: NOTA.

Garratt, James. 2019. Music and Politics: A Critical Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Grant, Morag J., Rebecca Möllemann, Ingvill Morlandstö, Simone Christine Münz, and Cornelia Nuxoll. 2010. “Music and Conflict: Interdisciplinary Perspectives.” Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 35 (2): 183–98.

Hebert, David G., and Jonathan McCollum. 2014. “Philosophy of History and Theory in Historical Ethnomusicology”. In Theory and Method in Historical Ethnomusicology, edited by Jonathan McCollum and David G. Hebert, 85–147. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους. [History of the Greek Nation]. 2000. 2nd ed. vol. XV. Athens: Athens Publishing House.

Kitromilides, Paschalis M. 2006. “Introduction: Perspectives on a Leader”. In Eleftherios Venizelos: The Trials of Statesmanship, edited by Paschalis M. Kitromilides, 1–8. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Kitsios, George. 2020. “Lost Voices and Singing Texts: Reconstructing the Cultural Past of Ioannina during the First Half of the 1870’s.” Series Musicologica Balcanica 1 (1): 384–96.

Mahon, Maureen. 2014. “Music, Power, and Practice.” Ethnomusicology 58 (2): 327–33.

Mavrogordatos, George Th. 1983. Stillborn Republic: Social Coalitions and Party Strategies in Greece, 1922-1936. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

———. 2015. 1915: Ο Εθνικός Διχασμός [1915: The National Schism]. Athens: Patakis.

McCollum, Jonathan, and David G. Hebert. 2014. “Foundations of Historical Ethnomusicology.” In Theory and Method in Historical Ethnomusicology, edited by Jonathan McCollum and David G. Hebert, 1–33. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Meizel, Katherine, and J. Martin Daughtry. 2019. “Decentering Music: Sound Studies and Voice Studies in Ethnomusicology.” In Theory for Ethnomusicology: Histories, Conversations, Insights, edited by Harris M. Berger and Ruth M. Stone, 176–203. New York: Routledge.

Noll, William. 1997. “Selecting Partners: Questions of Personal Choice and Problems of History in Fieldwork and Its Interpretation.” In Shadows in the Field: New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology, edited by Gregory F. Barz and Timothy J. Cooley, 1st ed, 163–88. New York: Oxford University Press.

O’Connell, John Morgan. 2010. “Introduction: An Ethnomusicological Approach to Music and Conflict.” In Music and Conflict, edited by John Morgan O’Connell and Salwa El-Shawan Castelo-Branco, 3–14. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

O’Connell, John Morgan, and Salwa El Shawan Castelo-Branco, eds. 2010. Music and Conflict. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Ochoa Gautier, Ana María. 2014. Aurality: Listening and Knowledge in Nineteenth-Century Colombia. Durham (NC): Duke University Press.

Rice, Timothy. 2017. “Ethnomusicology in Times of Trouble.” In Modeling Ethnomusicology, 233–54. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ritter, Jonathan, and Daughtry, J. Martin, eds. 2007. Music in the Post-9/11 World. New York: Routledge.

Samuels, David W, Louise Meintjes, Ana Maria Ochoa, and Thomas Porcello. 2010. “Soundscapes: Toward a Sounded Anthropology Further.” Annual Review of Anthropology 39: 329–435.

Said, Edward W. 1993. Culture and Imperialism. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Smith, Mark M., ed. 2004. Hearing History: A Reader. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

———. 2007. Sensing the Past: Seeing, Hearing, Smelling, Tasting, and Touching in History. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Sterne, Jonathan. 2012. “Sonic Imaginations.” In The Sound Studies Reader, edited by Jonathan Sterne, 1–12. New York: Routledge.

Stoever, Jennifer Lynn. 2016. The Sonic Color Line: Race and the Cultural Politics of Listening. Vol. 17. New York: NYU Press.

Stoler, Ann Laura. 2009. Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Street, John. 2012. Music and Politics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Wong, Deborah. 2014. “Sound, Silence, Music: Power.” Ethnomusicology 58 (2): 347–53.

———. 2017. “Deadly Soundscapes: Scripts of Lethal Force and Lo-Fi Death.” In Theorizing Sound Writing, edited by Deborah Kapchan, 253–76. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.