Singing with Whales: Exploring Human and Non-Human Connections

Marie Comuzzo

Brandeis University

Updated September 2024: Since the original publication of this piece, the author found out that Roger Payne’s wife, Katy, was instrumental in the discovery of whale songs. The web version of these findings has been reflected to include Katy’s crucial contributions and work against the continued erasure of women as knowledge producers in the twentieth century.

Can the conceptualization of other animals’ sounds as song shift humans’ perception of their consciousness and therefore their recognition as sapient species? And if so, what does that say about humans’ perceptions of music and the role it plays within our society? My paper explores how scholars discuss whales’ songs within various cultures and disciplines, and how connecting with whales through sound has different meanings depending on the cultural context. I discuss the global impact of hearing humpback whales’ sound production as song throughout the twentieth century and how Euro-American musicians responded to this singing. I also explore the long-standing spiritual interrelationship between the Iñupiaq people and the bowhead whale, as well as their ritual gift exchange through drumming and dance. While these examples come from very different cultural contexts (environmental global impact, Euro-American musicians, and Iñupiaq people), they reflect a deep desire and need to connect with whales through sound and be in communion with them through gift exchange.[1]

Humpback Whales’ Songs and Save the Whales

First recorded in 1952 by accident from a U.S. Navy installation in Hawaii, humpback whales’ sonic production has been studied for over seventy years, most notably by biologists and environmental activists Roger and Katy Payne (Payne and McVay 1971). After having a horrific encounter with a stranded dolphin that humans had brutally mutilated on a beach, the Paynes sought to find a way to shift humans’ perception of non-human animals from inferior objectified creatures to living, intelligent beings. In 1970, they released Songs of the Humpback Whale, an album containing a representative sample of humpback sound production, which sold over 125,000 copies, becoming history’s best-selling nature recording.

Figure 1. Roger Payne's Album, Songs of the Humpback Whale (1970). CRM Records.

Following the 1971 publication of a related paper by Payne and McVay, which examined the sound production of humpback whales and described it as a series of songs, changes began to unfold on a legislative level. In 1972, just shortly after Payne and McVay’s groundbreaking study and album release, both the Marine Mammal Protection Act and the Endangered Species Act were established. These were not merely responses to the research, but also the product of a broader cultural awakening to the intricacies of humpback whale communication, propelled by the collective efforts of millions of protesters worldwide. Furthermore, the work of advocacy movements such as Save The Whales, in conjunction with a newfound global awareness of humpback whales’ singing and care towards whales in general, arguably played a pivotal role in influencing the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (1972).[2] It also resulted in a ten-year moratorium on commercial whaling to reduce the capitalistic exploitation of the species that is still in place today (Dorsey 2013).[3]

The success of and interest in Songs of the Humpback Whale continued in the years to follow. In 1979, National Geographic sent their 10.5 million subscribers a flexi disc containing some of the original songs alongside commentary by Roger Payne (Rothenberg 2008). In the same year, the International Whaling Commission banned the hunting of all whale species by commercial ships and declared the Indian Ocean as a whale sanctuary.

Figure 2. National Geographic's release of Songs of the Humpback Whale on flexi disc (1979). CRM Records.

As a result of this increased awareness of the whales’ musical production, along with the continuing global protesting against whaling, more and more countries joined the International Whaling Commission, which banned commercial whaling worldwide in 1986 and declared the entire Southern Ocean a whale sanctuary in 1994 (Dorsey 2013).

Whales’ Sound Production: Song or Language?

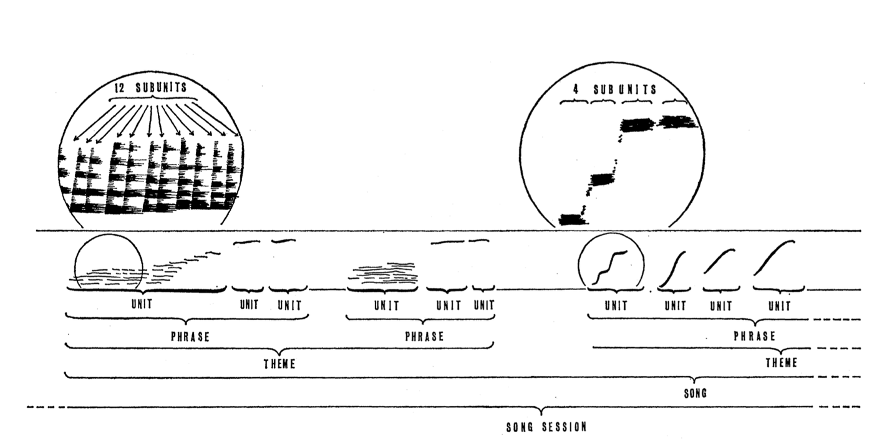

Payne and McVay focused initially on the detailed analysis of the humpbacks’ vocalizations, filtered through spectrographs that showed repeating patterns and overall structure. The authors compared whales to birds, arguing that although different in length and sonic spectrum, whales’ sound production should be classified as songs (Payne and McVay 1971, 590-1). They theorized and demonstrated this through the creation of a notation system that tracks different sonic elements of whale song and how they repeat over time, revealing clear patterns and even rhymes connecting the end of each musical phrase. While the authors discussed whale sound production in terms of song because of its structure and clearly defined pitch, the melody was not clearly marked or produced in a way that is immediately intelligible by the human ear.

Figure 3. Diagrammatic sample of whale spectrograms (also called sonograms). (Payne and McVay 1970, 586).

Today, scientists explore these forms of communication in terms of language and create devices to emulate whale calls underwater in efforts to establish a form of direct communication between humans and whales. Most noteworthy is the work of Michelle Fournet, widely discussed in the documentary Fathom (2021). Fournet and her team play back recordings of the humpbacks’ sound “whup” with underwater speakers to prompt and record their responses. In doing so, Fournet has demonstrated that the “whup” sound is a greeting. These studies significantly enhance our understanding of whale songs and language and are representative of meaningful attempts of interspecies communication.

Humpback Whale Song

The humpback whales’ best known sound production is characterized by high intensity vocal signals, organized in specific and complex structures that change over time. Ranging from five to thirty minutes long, though often averaging fifteen, they are repeated in sessions that last several hours (Bright 1985; Cory 2015). Male humpbacks sing songs with the same pitches and structure in unison at the beginning of each breeding season. As whales hear and share these songs across massive distances, the whole population is informed of the shifts happening across the oceans. Whereas male humpbacks are generally known to sing only when swimming alone, the simultaneous shifts in song patterns regardless of distance challenges their supposed solitude. Perhaps whales’ perception of closeness is dramatically different from humans’, and while male whales are perceived as being on their own, they might not feel that way at all. This hypothesis would explain the importance that whales attribute to being able to hear each other in terms of location and geographical direction. As the oceans become noisier, their song’s reach is often impeded. This devastatingly results in members of the community becoming lost, ending up in freshwater or in waters too shallow to survive.

In terms of their singing, it is not clear whether they engage in a communal singing activity, if individuals adjust their tunes while responding to others, or have a completely different system altogether (Allen 2022). Solitary males predominantly sing in the winter and during mating season, so scientists have attributed their calls to mating behaviors. Other scholars have hypothesized that female whales evaluate male whales’ singing and presumably select the best singer for mating. There is even a scientific hypothesis that whales are participating in a cultural evolution, which leads them to create new songs, and that females prefer novelty (Garland 2021; Mundy 2018). Yet, no conclusive work has explicitly traced female whales’ appreciation of a singing male. Furthermore, males often sing alone, which also undermines the scientific assumption that the songs are mating calls (Schulze 2022).

I find these specific attempts to determine the purpose of humpback whales’ singing more an indication of Western society’s heteronormative and reprosexual formulation of life rather than an explanation of why whales sing. As Michael Warner points out, “reprosexuality involves more than reproducing, more even than compulsory heterosexuality; it involves a relation to self that finds its proper temporality and fulfillment in generational transmission” (Warner 1991, 9). The projection of heteronormative assumptions onto male humpbacks is a testament to the human tendency to anthropomorphize and assign human gender roles to non-humans. More recently, scholars such as Jack Halberstam have critiqued such assumptions, noting how “humans projects all of [their] uninspired and unexamined conceptions about life and living onto [non-human] animals, who may actually foster far more creative or at least more surprising modes of living and sharing space [than us]” (Halberstam 2011, 34). Both scholars, through queer methodologies and the critical engagement of the anthropomorphizing nonhuman animals, challenge heteronormative ideologies that are both limited and limiting. Here I argue that formulating whales singing strictly as mating behavior undermines a more holistic perception of their songs. This interpretation limits the significance of their lives, instead of acknowledging their songs as potential manifestations of beauty, creativity, and care.

Sounding Whales and Interspecies Impromptu

In addition to strictly scientific studies of whale songs, musicians have listened and played alongside whales, practicing different ways of making sense of their songs. Paul Winter is an American saxophonist who pioneered the interweaving of non-human sounds with a combination of jazz and Earth music. After attending Payne’s lecture about humpback whales’ sound production in 1968, Winter created accompaniment to their songs, and improvised extemporarily with them. His composition “Lullaby from the Great Mother Whale for the Baby Seal” in Callings (1980) and in his later album with Paul Halley, Whales Alive! (1987), is particularly moving; it highlights, and arguably translates, a fragment of a whale song into a piece that is easily understood by the human ear. Winter plays a short phrase with a precise melody that repeats several times and is well defined in its pitches, echoing the whale’s initial melody. By prolonging the whale’s singing, emphasizing the melody through his own playing, and adding a guitar accompaniment both to his playing and the whale’s singing, Winter successfully creates a musical composition that sounds as though the whale and the human are truly playing together. He even finds ways to improvise on the original melody while incorporating the whales’ sound, as though they are responding to each other. The piece is a profound example of an empathic reception of sound and a caring way of treating other species’ sonic material in a non-hierarchical way.

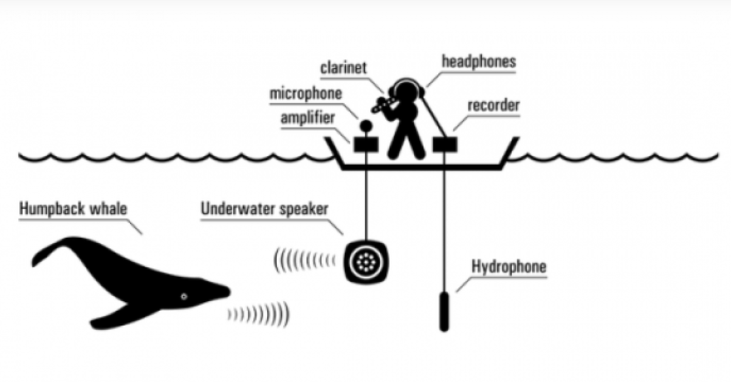

Following the steps of Paul Winter, David Rothenberg furthered this improvisational practice by creating a sonic system to improvise synchronously with humpback whales.

Figure 4. Rothenberg's method to improvise alongside humpback whales.New Jersey Institute of Technology. “Professor David Rothenberg & His Orca-stra for Humpback Whales.” Published November 4, 2019. (Link)

He plays his clarinet into a microphone and amplifier connected to an underwater microphone that projects the sound into the water. The hydrophone, connected to a recorder, then picks up the responses of the humpback whales (video). The collection of these improvisations was released in 2022 as an album titled Who Knows Why Whales Sing, which also features tracks inspired by a 24-channel sound installation at the Bergen Natural History Museum in Norway (video) and combines sounds of many different whale species. This album is an additional testimony to the communication that is already happening between humans and whales and a celebration of the beauty and complexity of whale sounds. By listening to the voices of the whales playing alongside them, Rothenberg invites us to reflect on our own relationship with nature and our responsibility in caring for other beings and creating a more sustainable and inclusive world.

People of the Whale

Recent studies on the sound of whales among scientific communities is based on effectively emulating the actual sounds and patterns that whales produce. However, these studies have overlooked the inclusion of Indigenous knowledge. Yet, histories reflecting meaningful inter-species connections between humans and whales have been transmitted for over four hundred generations in many cultures across the globe, underscoring Western scholarship’s limited consideration of non-Western knowledge. I was first introduced to Chie Sakakibara’s work through Jim Sykes’s article “The Anthropocene and Music Studies” (Sykes 2020), which considerably shifted my perception of what (ethno)musicology can be. This opened a space to understand how different forms of spirituality restructure what music is and how we might study it. As an Italian non-immigrant alien studying in the US, I am aware of the privilege I hold and the complexity of my positionality when engaging with Indigenous epistemologies. For this reason, I have chosen to amplify voices of the Iñupiat or People of the Whales through the work of Chie Sakakibara, to listen to holistic ways of being in relation to sound and whales, and to think alongside their epistemology (Alcoff 1991).

Chie Sakakibara is an adopted member of the Iñupiaq communities of Utqiagvik and Point Hope in Alaska (Sakakibara 2020) and an Associate Professor of Geography, Environmental, and Native American studies at Syracuse University. In her work, she interweaves the effect that climate change has on the culture and spirituality of Iñupiat. When discussing the importance of the relationship between Iñupiat and bowhead whales, Sakakibara explains that “humans and whales are frequently interchangeable in Iñupiaq tales and songs,” and for Iñupiat to be people, they need the whale (Sakakibara 2020, 16). One of the villagers from Point Hope, Steve Oomittuk, says,

The whale is at the heart of our world, everything. They bring us music. Our drums are made from the membrane of the liver of the whale. They make us sing, dance, and tell stories. Without whales, we lose our spirituality. It's been always like this. It's the gift of the whale. Without whales, you don't dance. (Sakakibara 2020, 165).

One major component of Sakakibara’s work is how Iñupiat respond to severe shifts in climate patterns. Fannie Apik, a traditional Iñupiaq performer, explains that drumming opens the conversation between humans and whales and enables their community to survive through change, saying,

If we need to change things to survive, then we ought to. If we have no whales, then we really do need to have more music. It would help us and our souls tune into the mind of the whales. We also say the whale is always looking for a village with good music. Drum music may become our last hope to keep our relationship with the whale. (quoted in Sakakibara 2009, 300).

Their drumming continues to strengthen their relationship through the heartbeat that connects human and whale. In this, the sacred calling of the whale, the whale and the people themselves, and their identities are brought together through drumming, dancing, and singing—in a confluence of identities that make Iñupiat the People of the Whales (Sakakibara 2010; 2011a; 2011b; 2017; 2020).

Concluding Thoughts

The exploration of human and whale connections as mediated through sound highlights the intricate fabric of interspecies relationships. As discussed throughout, the discovery of whales’ singing among Western settler scientists in the United States and within popular culture globally has led to a significant reduction of their capitalistic exploitation. This reveals once more the power that people coming together has in shaping our way of caring for each other and underscores the responsibility that corporate industries and governments have in determining who has the right to live and who can be relentlessly exploited (Ritchey 2021). It is evident that as we find ways to move forward, it is fundamental to strengthen our commitment to shift our ways of life. By deeply listening to alternative ways of being in relation to other humans and non-humans that respect our place on Earth, we cultivate a more holistic perception of ourselves as integral parts of a much broader ecosystem. This awareness empowers us to demand and affect change at the governmental level, halt the relentless exploitation of life and nature, and foster a more integrated and respectful way of being human.

Gratitude Statement

My deepest gratitude to Marianna Ritchey for her invaluable mentorship, guidance, and constant support throughout my academic journey, and her indispensable comments and suggestions. I extend my sincere thanks to Bradford Garvey for directing me towards new ways of making sense of music and for his enduring support for this project. I am also grateful to Anna Valcour, both for being an exceptional colleague and friend and for her detailed review of multiple drafts of this article. Lastly, my gratitude extends to the anonymous reviewers whose insightful comments significantly enhanced the quality of this essay.

Notes:

[1] Here I reference sonic generosity and music as a gift, as formulated by Jim Sykes (2018, 2020).

[2] This was the first UN major conference on international environmental issues and a turning point in the development of international environmental politics. For a full report of the conference see, “Report of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment,” Stockholm, 5-12 June, 1972, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/NL7/300/05/IMG/NL730005.pdf?OpenElement.

[3] Whaling became widespread largely due to the increasing demand for the oil derived from whales’ body fat, which was considered the best form of lamp fuel in the 18th and 19th centuries. This demand led to a significant increase of whaling activities, fueling a capitalistic cycle of profit and the commodification of whales. This capitalistic exploitation had severe ecological implications, including the near extinction of several whale species and significant disruption of marine ecosystems. It also reduced whales to commodified beings whose lives were less meaningful than the oil that could be derived from their bodies.

References

Alcoff, Linda. 1991.“The Problem of Speaking for Others.” Cultural Critique 20, no. 20: 5–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/1354221.

Allen, Jenny, Ellen C. Garland, Claire Garrigue, Rebecca A. Dunlop, and Michael J. Noad. 2022. “Song Complexity is Maintained During Inter‐Population Cultural Transmission of Humpback Whale Songs.” Scientific Reports 12, no. 8999: 1-9.

Bright, Michael. 1985. Animal Language. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

Cory, Lara C. 2015. “The Secret of the Deep.” In Animal Music: Sound and Song in the Natural World, 29-32. London, UK: Strange Attractor Press.

Dorsey, Kurk. 2013. “National Sovereignty, the International Whaling Commission, and the Save the Whales Movement.” In Nation-States and the Global Environment, edited by Erika Marie Bsumek, David Kinkela, and Mark Atwood Lawrence, 43–58. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Garland, Ellen C., Claire Garrigue, and Michael J. Noad. 2021. “When Does Cultural Evolution Become Cumulative Culture? A Case Study of Humpback Whale Song.” The Royal Society Publishing 377, no. 1843.

Halberstam, Jack J. 2011. The Queer Art of Failure. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Lossius, Trond. 2019. “David Rothenberg Improvising in The Whale Hall.” Vimeo. Video, 43:04. https://vimeo.com/373200709.

Mundy, Rachel. 2018. Animal Musicalities: Birds, Beasts, and Evolutionary Listening. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Mustrill, Tom. 2022. How to Speak Whale: A Voyage Into the Future of Animal Communication. New York: Grand Central Publishing.

New Jersey Institute of Technology. “Professor David Rothenberg & His Orca-stra for Humpback Whales.” Published November 4, 2019. https://news.njit.edu/professor-david-rothenberg-his-orca-stra-humpback-whales.

Payne, Roger S., and Scott McVay. 1971. “Songs of Humpback Whales: Humpbacks Emit Sounds in Long, Predictable Patterns Ranging over Frequencies Audible to Humans.” Science 173, no. 3997: 585–97.

Payne, Roger and Katy Payne, producers. 1970. Songs of The Humpback Whale. Del Mar: CRM and Capitol Records SWR 11, vinyl.

Ritchey, Marianna. 2021. “Resisting Usefulness: Music and the Political Imagination.” Current Musicology 108: 26-52.

Rothenberg, David. 2010. Thousand-Mile Song: Whale Music in a Sea of Sound. New York: Basic Books.

———. 2014. “David Rothenberg Plays Live with Humpback Whales in Hawaii.” YouTube video, 2:09. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=807LSbW28Po&t=13s.

———. 2022. Who Knows Why Whales Sing. Terra Nova Music. Produced by David Rothenberg. Online Album. https://open.spotify.com/album/1i357tsknJrnQDjzRc7Dtc?si=CWFOooHIQOmr0K2CXJ95jw

Sakakibara, Chie. 2009. “‘No Whale, No Music’: Iñupiaq Drumming and Global Warming.” Polar Record 45, no. 235: 289–303.

———. 2010. “Kiavallakkikput Aġviq (Into the Whaling Cycle): Cetaceousness and Climate Change Among the Iñupiat of Arctic Alaska.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 100 (4): 1003–12.

———. 2011a. “Climate Change and Cultural Survival in the Arctic: Muktuk Politics and the People of the Whale.” Weather, Climate, and Society 3 (2): 76–89.

———. 2011b. “Whale Tales: People of the Whales and Climate Change in the Azores.” FOCUS on Geography 54 (3): 75–90.

———. 2017. “Northern Relations: Colonial Whaling, Climate Change, and the Inception of a Collective Identity in Northern Alaska and Northern Atlantic.” In Critical Norths: Space, Nature, Theory, edited by Sarah Jaquette Ray and Kevin Maier, 139–70. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

———. 2020. Whale Snow: Iñupiat, Climate Change, and Multispecies Resilience in Arctic Alaska. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Schulze, Josephine N., Judith Denkinger, Javier Oña, Michael M. Poole, Ellen Garland, and Lies C. Zandberg. 2022. “Humpback Whale Song Revolutions Continue to Spread from The Central Into The Eastern South Pacific.” The Royal Society 9, no. 8.

Sykes, Jim. 2018. The Musical Gift: Sonic Generosity in Post-War Sri Lanka. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

———. 2020. “The Anthropocene and Music Studies.” Ethnomusicology Review 22, vol. 1: 4-21.

Warner, Michael. 1991. “Introduction: Fear of a Queer Planet.” Social Text 29, 9/4: 3-17.

Winter, Paul. 1980. Callings. Living Earth Music Production. Produced by Paul Winter. Online Album. https://paulwinter.com/callings/.

———. 2015. “Lullaby From the Great Mother Whale For the Baby Seal Pups.” YouTube video, 5:05. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7i7mRuyKU1s.

Winter, Paul and Paul Halley. 1987. Whales Alive!. Living Earth Music Production. Produced by Paul Winter and Roger Payne. Online Album. https://paulwinter.com/whales-alive/.

Xanthopoulos, Drew, dir. 2021. Fathom. Apple TV+. Video Documentary.