The Sound of Old Shanghai in Music Recordings:

Hearing Through the Gramophone

Shuang Wang (Peabody Institute) [1]

Old Shanghai [2] music has become a topic of renewed attention in Chinese mass media. Through audio processing, newly created works, like “Miss You” (niàn nǐ 念你),[3] deliberately filter out some frequencies and add artificial noise to mimic the sound of gramophone recordings. There are also songs that straightforwardly add old samples like “South Hill Is in The South” (nán shān nán 南山南).[4] Such designs in music produce a nostalgic ambiance for modern Chinese audiences.

How is this Old Shanghai ambiance created? How do we hear this ambiance in music recordings? Old Shanghai popular music culture began to form in the 1920s and reached its peak in the 1940s under the colonial governance of the Shanghai International Settlement. Such a development seemingly ran counter to the prevailing chaos of the Warlord Era,[5] World War II, and the economic downturn outside the colony. Although many revolutionists at this time were clamoring to create inspirational patriotic music, a group of musicians in Old Shanghai continued to produce music about love, alcohol, and money as “spiritual narcotics” (jīng shén má zuì jì 精神麻醉剂) (Xu and Zhou 2015, 184). These songs in the 1920s–1940s, which enjoyed commercial success, incorporated Chinese folk tunes with Western scales and instruments.

The thin and soft female voices in these old song recordings have become a trademark, making the Old Shanghai sound instantly recognizable. Preference for this voice might have originally been inspired by the singing skills of Peking Opera and Kunqu,[6] as well as the Wu dialects.[7] While the voice’s characteristics were set by the influence of regional habits and aesthetics, they were further consolidated and amplified by music recording technology, specifically the gramophone, as its recording capacity could only capture part of the frequency spectrum accurately. Together with mechanical and rumbling noises formed during the production process, the gramophone renders the human voices thin and constrained with a muffled sound.

Gramophone recording underwent technological innovation during the Old Shanghai period. Before 1925, acoustical recording was the primary method; the new technology of electrical recording was first put into production in 1925 (Yale University Library, n.d). But whichever method was used to pick up the sounds, the recording process culminated in transferring the analog signals into the mechanical system driving the cutting stylus on the master disc to form grooves (Horning 2020, 110–13). Although the new method of electrical recording eventually expanded the possible frequency range from pre-1920s’ 200–2000Hz to 100–8000 Hz, it was still not enough for the gramophone to pick up many sounds like the machines after the 1970s.

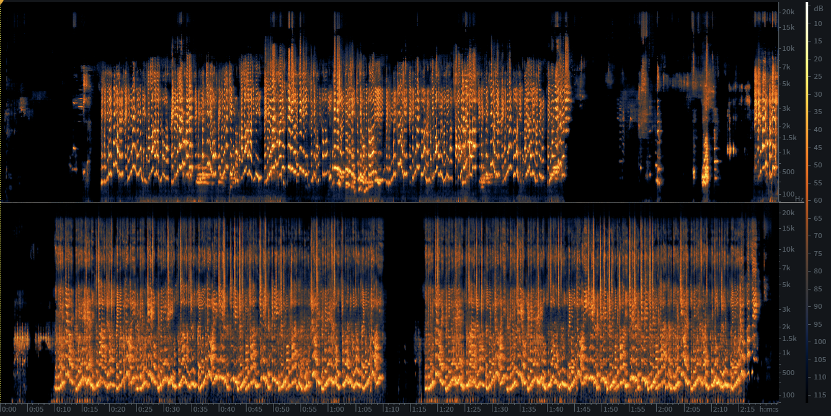

Many might think that the Old Shanghai music style is a product of the artistic choice of its time, yet the technology of the gramophone also significantly shaped the impressions it gave listeners. Specifically, the songs preserved in pre-1950s 78 rpm gramophone records have become the main source of people's exposure to Old Shanghai music. Compared to the gramophone’s analog recordings, the digital recordings of post-1970s CDs represent a qualitative leap in the preservation of sounds, which precipitated a transformation in the styles and textures used. To demonstrate, Figures 1 to 3 chart two versions each of three songs—“When Will You Come Again” (hé rì jūn zài lái 何日君再来) (Fig. 1), “Rose, Rose, I Love You” (méi guī méi guī wó ài nǐ 玫瑰玫瑰我爱你) (Fig. 2), and “The Evening Primrose” (yè lái xiāng 夜来香) (Fig. 3)—as examples to analyze the difference in audio playback caused by sound pickups.

Using spectrogram analysis software to adjust the gains of vocals and accompaniment, the singers’ voices in these recordings can be mostly separated from the instrumental lines, as shown in the figures below.

Fig. 1: Upper: analog recording (Sung by Zhou Xuan 周璇; Released 1937); Lower: digital recording (Sung by Teresa Teng 邓丽君; Released 1984).

Fig. 2: Upper: analog recording (Sung by Yao Li 姚莉; Released 1941); Lower: digital recording. (Sung by Feng Fei Fei 凤飞飞; Released 1985).

Fig. 3: Upper: analog recording (Sung by Yoshiko Yamaguchi 山口淑子[8]; Released 1944); Lower: digital recording (Sung by Teresa Teng 邓丽君 ; Released 1994)

*Red box: The approximate vocal range of female singers under common circumstances

In the example figures, the vertical axis is the frequencies of sound (unit: hertz), and the horizontal axis is the music timeline. The brightness of color represents sound volume (unit: decibel). Comparing these figures, we can clearly see that the bright color is more evenly distributed, with more detail crossing through all audible frequencies, in the lower cases (post-1970s recordings). Although there is not much difference in the overall volume between the two versions, the effective sound is quite distinguishable from the visualized figures. When the sound is graphed, the upper recordings show a narrower or dotted color in specific frequencies, resulting in many color faults that did not capture sounds in between horizontal layers. Compared to Old Shanghai song recordings from before the 1950s, contemporary recording technology can present a much fuller image of the recorded human voice. We can conclude that the pre-1950s gramophone recordings were less sensitive to sound pickup, and thus in particular led to a thinner voice in between approximately 200–1100 Hz of these female singers’ vocal range (as noted in Fig. 3). The voice coming from the gramophone appears to be a unique “censored” feature that ultimately catalyzed the Old Shanghai style.

Another interesting point about the comparisons above is the discrepancy of pitches they reveal. The more recent re-recordings show lower pitch levels when comparing the main voice lines, and the female singers’ voices are relatively thicker with a more detailed audio spectrum shown in figures in later recordings. When listening to music live or through modern hi-fi playback devices, the human ear can receive high-frequency transmissions evenly, including harsh sounds. However, gramophone listening is different. As shown in the figures, the recording process tends to cut off part of the high-frequency sound, especially some overtones. Although the singers were singing relatively high notes, the recordings of their voices would still sound soft. Additionally, to achieve a balance of treble and bass pickup during the mechanical recording of the gramophone, a high pitch of singing would have been favorable since it allowed the voice to sound more prominent and made it more easily distinguishable from the instrumental accompaniment. The female voice was more likely to achieve the desired effect, and this preference for high voices may have also led to an inclination for female singers instead of males in Old Shanghai music.

In Theodor W. Adorno’s research on musical mass media, such as radio and the phonograph, he contended that the new technological means made the “structural” appreciation of music disappear (Adorno 1976, 129-130), leaving music listening to occur in a state of distraction. Looking at his argument from another perspective, the emergence of new media also prompted the construction of a new norm of listening to music. In this norm, the sonic markings brought about by technologies directly affect the receiver’s listening experience and shape their impression of the music.

With the technology of gramophone as the medium, Old Shanghai music was limited in terms of sound quality, singers’ performance, texture, style, genre, recording duration, and even the choice of the singers’ gender. This steered the musical culture and industry of Shanghai from the 1920s to the 1940s into a specific trajectory. The gramophone, in a Latourian sense a non-human actant (Latour 1996, 373), helped determine the aesthetic and commercial preferences for music practitioners and listeners of Old Shanghai by imbuing a special sonic identity to the music.

This very period-specific music engraved on gramophone discs is deeply imprinted in the understanding of people immersed in Chinese culture and continues to influence current trends. Through the tireless efforts of technicians over the last century, modern recording technology can easily capture sounds that even exceed the scope of the human ear if one desires. For our time, in most recording cases, technical breakthroughs are no longer a primary concern. The pursuit of a lo-fi and hazy auditory experience, as provided by gramophone records, has returned as nostalgic enjoyment. This soft and thin female voice becomes the most immediate impression of the music, imitated and sampled in modern retro works, and collected by retro-fashion followers.

List of Recorded Sources:

Digitalized 78 rpm Gramophone Records:[9]

1. “When Will You Come Again” (hé rì jūn zài lái 何日君再来)

Publisher: Shanghai Pathé Records

Matrix number: B173

2. “Rose, Rose, I Love You” (méi guī méi guī wó ài nǐ 玫瑰玫瑰我爱你)

Publisher: Shanghai Pathé Records

Matrix number: B597

3. “The Evening Primrose” (yè lái xiāng 夜来香)

Publisher: Shanghai Pathé Records

Matrix number: B837

Provided by: China Record Group Co., Ltd

1980s Records in Digital Format:

1. “When Will You Come Again” (Third version of Teresa Teng)

Initial Publisher: Taurus Records (Japan) Inc.

Provided by: Universal Music Ltd. through QQ Music

2. “Rose, Rose, I Love You”

Initial Publisher: Fujit Music Co., Ltd.

Provided by: Fujit Music Co., Ltd. through QQ Music

3. “The Evening Primrose” (Second version of Teresa Teng)

Initial Publisher: Taurus Records (Japan) Inc.

Provided by: Universal Music Ltd. through QQ Music

Notes:

[1] This article would not have been possible without the guidance of my advisor, Dr. Laura Vasilyeva, and the technical support of my friend, Mr. Haoran Li.

[2] Old Shanghai generally refers to a historical period after the Qing dynasty and before the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) from 1912 to 1949. In terms of contemporary Chinese music history, Old Shanghai can refer specifically to a period from the 1920s to 1940s in colonized Shanghai, where urban entertainment industries developed rapidly.

[3] Sung by Bella Yao (姚贝娜), released by Huayi Brothers Music (Bejing) in 2015.

[4] Sung by Ma Di (马頔), released by Modern Sky Records in 2014.

[5] A historical period in China between 1916 and 1928, during which the Beiyang Army and other regional military forces were controlling most of the country separately.

[6] Traditional Chinese Operas formerly popular in Old Shanghai that required young female characters to present high and sharp voices.

[7] A tender-speaking Chinese dialect, compared to Mandarin and other dialects, with many glottal stop syllables spoken in and around Shanghai.

[8] More widely referred to in print by the Chinese name Li Xianglan 李香兰

[9] The digitized records are part of the Digital Repository of Chinese Old Records (中华老唱片数字资源库) Project supported by PRC’s 12th Five-Year Plan for the National Cultural Reform and Development.

References:

Adorno, Theodor W. 1976. “Musical Life” In Introduction to a Sociology of Music. translated by E. B. Ashton, 118-37. New York: Seabury Press.

Horning, Susan S. 2020. “Recording Studio in the First Half of Twenties Century.” In The Bloomsbury Handbook of Music Production, edited by Simon Zagorski-Thomas and Andrew Bourbon, 109-24. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Latour, Bruno. 1996. On Actor-Network Theory: A Few Clarifications. Soziale Welt, 47 (4): 369–81.

Xu, Guoyuan 徐国源 and Xiaoyan Zhou 周晓燕. 2015. 上海老歌:一种记忆性声音的消费神话 [Shanghai Old Songs: A Consumption Myth of Voice in Memory]. 江苏社会科学 [Jiangsu Social Science] no. 2: 182-87.

Yale University Library. n.d. “The History of 78 RPM Recordings.” Accessed January 22, 2022. https://web.library.yale.edu/cataloging/music/historyof78rpms.